Under his highly acclaimed statistical system, noted writer and Sabermetrician Bill James fails to give out win shares to coaches. That’s perfectly understandable—after all, what tangible impact do most coaches really have?—but if James somehow managed to include the manager’s trusted lieutenants, he’d have to give at least a half-share to former Yankee first base coach Jose Cardenal for a brilliant piece of advice he provided during the 1996 World Series.

With the Yankees holding onto a 1-0 lead in the ninth inning of Game Five, the Atlanta Braves threatened to tie the score—and possibly win the game. As Chipper Jones led off third base and Ryan Klesko took his lead at first base, Luis Polonia stepped into the batter’s box against Yankee closer John Wetteland. Moments before the at-bat, Cardenal noticed that Paul O’Neill was out of position in right field. From his perch in the dugout, Cardenal waved frantically at O’Neill, motioning him to move several steps toward right-center field. Surely enough, Polonia then swatted a Wetteland delivery toward the right-field alley, high and far, but short of home run distance. Racing toward the wall, O’Neill finally caught up with the drive, barely snaring it in the webbing of his glove before slapping his hands against the padded wall at Fulton County Stadium.

If Cardenal had not moved O’Neill several feet toward the gap, Polonia’s drive would have eluded him. At the very least, Jones would have scored, tying the game. Although it’s not a certainty, Klesko very possibly would have scored from first, giving the Braves a dramatic come-from-back victory. And who knows how the Yankees would have reacted in Game Six, now down three games to two and emotionally devastated by a ninth-inning loss on the road. So who knows if the Yankees even win the 1996 World Series without the strategic re-positioning performed by Cardenal.

So that’s how most Yankee fans will remember Cardenal. Still, his days as one of Joe Torre’s lieutenants tells only a fraction of his fascinating journeys throughout baseball. It’s been a wild ride, aided and abetted in part by some of Jose’s unusual personality quirks.

A journeyman outfielder who broke into the big leagues in the 1960s, Cardenal came up through the San Francisco Giants’ system as a coveted prospect with five-tool talents. Scouts loved Cardenal’s speed, arm strength, and developing power. Sadly, the Giants did a poor job in evaluating their young players and prospects and didn’t always handle their Latino players fairly at the time; along those lines, they traded Cardenal to the Angels for fringe back-up catcher Jack Hiatt. The trade to the American League gave Cardenal a chance to play games head-to-head against his cousin, Kansas City A’s shortstop Bert "Campy" Campaneris. (In a rather remarkable coincidence, Cardenal became the first batter to step in against his cousin when Campy moved to the mound as part of Charlie Finley’s nine-positions-in-a-day stunt in 1965.) Showing promise in his first two seasons with the Angels, Cardenal then flopped in his third year, prompting a trade to the Cleveland Indians for utilityman Chuck Hinton. Cardenal played two seasons by the lake before packing his bags again; this time, the Indians traded him back to the National League, more specifically to the St. Louis Cardinals.

The Cardinals, playing half of their games on the expansive artificial turf of Busch Stadium, seemed like an ideal fit for a fast flychaser like Cardenal. (He also became "Cardenal the Cardinal," creating all sorts of marketing possibilities.) With Cardenal in center and Lou Brock in left field, the Cardinals featured speed galore in the outfield. Yet, the marriage between Cardenal and the Cardinals didn’t last. After a season and a half, the Redbirds dealt Cardenal to Milwaukee in a midsummer trade. It would not be until his next stop that Cardenal would find some long-term stability. After the 1971 season, the Cubs packaged right-hander Jim Colborn with two lesser players and sent them to the Brewers for Cardenal. Grouping him with Billy Williams (left field) and Rick Monday (center field), the Cubs formulated one of their best outfields in years, consisting of a Hall of Famer (Williams) and two players with the speed to cover center field (Cardenal and Monday). Cardenal, who would remain a fixture in front of the Wrigley Field ivy for six seasons, had finally found a home. (It would also be during his days in Chicago that Cardenal would develop his trademark king-sized Afro; more on that development later.

Then came Cardenal’s decline phase. With the Cubs realizing that the 33-year-old Cardenal could no longer play every day, they traded him to the Philadelphia Phillies after the 1977 season. He struggled as a bench player with Philly, found himself traded to the New York Mets in the middle of a doubleheader, and endured two more half-seasons of utility play with the lowly Mets before enjoying a last hurrah with the 1980 Kansas City Royals. Signed off the waiver wire in late August, Cardenal batted .340 in 53 at-bats and then delivered a pinch-hit in the ninth inning of Game Six of the World Series. Even though his hit against Tug McGraw ultimately didn’t matter in the Royals’ loss, it did allow Cardenal to leave his major league career on the high note of a World Series single.

So why did Cardenal, a solid ballplayer who hit for a decent average, stole bases aggressively, and played all three outfield positions to a capable level, find himself suiting up in nine different uniforms over a journeyman 18-year career? Two factors may have been at work. First, Cardenal didn’t hit with the kind of power that he had flashed as a prospect in the Giants’ system. Satisfied with spraying the ball from alley to alley, he never hit more than 17 home runs in a single season. Second, Cardenal may have aggravated some of his teams with his behavior, which was either quaint or bizarre, depending on your perspective. Some of his managers considered him moody, though that could have resulted from racial and ethnic misunderstanding. A free spirit with an odd sense of logic, Cardenal did frustrate his managers and front office bosses with his quirks and habits. Some of those habits damaged his reputation, while others were flat-out harmless, but all of them made Cardenal one of a kind:

*Cardenal liked to wear his uniform pants exceedingly tight at a time when most players preferred the baggier look of the late 1960s. According to former Seattle Pilots right-hander Fred Talbot, Cardenal once sat out three straight winter league games because he couldn’t find pants that were tight enough around his legs. And yes, that does sound like something out of a Seinfeld episode.

*As illustrated by Talbot, Cardenal became legendary for concocting strange excuses for an inability to play. In addition to the "tight pants" episode, there were bizarre eye injuries and nighttime distractions created by thoughtless crickets. In 1972, Cardenal claimed that he couldn’t see properly. The reason? He had woken up with his eyelid and his eyelashes stuck to his eyeball. "I woke up and my eye was swollen shut," Cardenal explained to a reporter without snickering. "My eyelashes were stuck together. I couldn’t see, so I couldn’t play." On another occasion, Cardenal told Cubs manager Jim Marshall that he couldn’t play in a 1972 spring training game because some particularly loud crickets had kept him up the entire night. Marshall didn’t believe him, but gave the veteran outfielder the day off. When it came to odd excuses not to play, Cardenal was the Chris Brown of the 1970s.

*Unlike many Latino players of his era, Cardenal spoke English well enough to give him a comfort level with reporters. Sometimes, his ability to handle interviews translated into too much irreverence for some people’s liking. When teammate Rick Monday rescued an American flag from two migrant workers in a 1976 game, Cardenal became one of the few players to react with a level of derision. He sarcastically wondered whether Monday would be regarded as much of an American patriot as Lincoln or Washington.

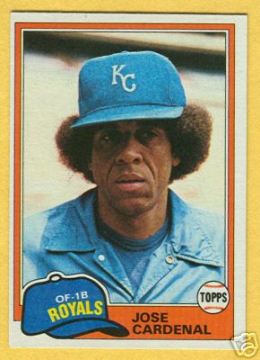

*Cardenal became well known for sporting one of the game’s largest Afros of the 1970s. In fact, other than Oscar Gamble, no one had an Afro the height or girth of Cardenal’s. As a result, Cardenal required caps and helmets that were appreciably larger than his head size—somewhere in the Bruce Bochy/Hideki Matsui range. That necessity is well illustrated in his final Topps card (1981), which shows Cardenal wearing the cap and colors of the Royals.

*According to Pete Rose (I guess you have to consider the source with this one), Cardenal corked bats blatantly during his days in Philadelphia. Rose says he could plainly hear the "sounds of the drill" in the Phillies’ clubhouse, as Cardenal plied his woodwork to a variety of bats. Rose claimed that he used one of Cardenal’s corked bats in batting practice, but never in an actual game.

In spite of his reputation for offbeat, sometimes daffy behavior, Cardenal went on to enjoy a long career as a coach, gaining respect for his knowledge of baserunning and outfield play, including his days with the Yankees. But now he finds himself in baseball limbo. In November, the Washington Nationals chose not to renew his contract as an advisor to GM Jim Bowden, leaving him unemployed. Rumors then swirled that Torre might reunite with Cardenal by bringing him to Los Angeles to serve as one of his coaches, but that never happened. So for the moment, Cardenal’s career in baseball, which has continued uninterrupted since the early 1960s, seems to be at a crossroads. It would be a shame if there were no place in the game for a coach—and a character—like Jose Cardenal.

Bruce Markusen writes "Cooperstown Confidential" for MLB.com. He always appreciates feedback—along with monetary donations—at bmark@telenet.net.