As impressionable youngsters growing up in Westchester County in the late sixties and early seventies, we reveled in imitating unusual batting styles and stances. Our favorite style to mimic was that of Willie Stargell, with his intimidating "windmilling" of the bat as he waited the next offering from a quivering pitcher. Then there was Joe Morgan’s patented "chicken-wing"—the repeated flapping of his left elbow to his side, a timing mechanism that became the signature of one of the era’s dynamic offensive stars. From the Yankees’ perspective, no one had a more distinctive stance than Roy White. Hitting out of a pronounced crouch, White tucked the knob of his bat toward his back hip, all while pointing each of his feet inward—toward the other. That latter trait characterized White’s signature pigeon-toed stance, one that I can’t remember any other player using in that era, or ever since, for that matter. I can’t imagine trying to stand pigeon-toed for any length of time, not to mention trying to do so while fending off a Bert Blyleven curveball or a Sam McDowell fastball.

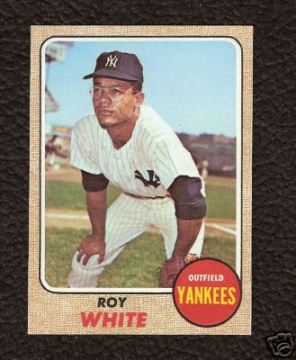

During that interim period of Yankee frustration that bridged 1965 to 1975, only a few Yankees garnered rabid fan followings in the Bronx. Most of us gravitated to stars like Thurman Munson and Bobby Murcer, or to a lesser extent, pitching stalwarts Mel Stottlemyre and Sparky Lyle. Few Yankee fans seemed to have much of an appreciation for Roy White, the team’s third best position player behind Murcer and Munson. White first became a regular in 1968, the year that this Topps card (No. 546, as shown above) was issued. There are a few alarmists who will contend that his skin color played a part in his lack of recognition. I’m sure it was a factor for some fans, but I don’t think it mattered much to us rabid diehards growing up near the Bronxville-Yonkers border. (After all, Mets fans in my neighborhood loved Willie Mays as much as any New York ballplayer in 1972 and ’73, even as his skills deteriorated badly.) White just happened to be very quiet, a player who never showed his temper (like Munson) or expressed himself outspokenly (as Murcer did at times). He wasn’t controversial; in fact, he was the opposite, he was as bland any player who ever wore pinstripes. And there’s nothing wrong with bland—if you’re good.

White was a very good player, but most fans (even the adults) of that time failed to recognize just how good. Given that Sabermetrics was in its infancy in the early 1970s, players like White tended to be underrated. As an all-around player who did a little bit of everything, nothing in White’s game stood out. He didn’t hit with a lot of power, so that certainly didn’t grab headlines. One of White’s greatest skills, his patience at the plate and ability to consistently walk more than he struck out, was not yet fully appreciated by either the fan base or the mainstream media. During his peak from 1968 to 1976, White had only one season in which his on-base percentage dipped below .350. In 1972, he led the American League in walks. And for his career, he drew 934 walks while striking out only 708 times.

As overlooked as White was for most of his career, the view of his worth as a player has undergone a stark revision. Historians and analysts now recognize him as one of the finer multi-talented players of the 1970s. Durable and dependable, he featured speed (stealing an average of over 15 bases a season over a 15-year career), a modicum of power (160 home runs, including a high of 22 in 1970), and an excellent glove in left field, skilled enough to handle the challenging dimensions of Death Valley of Yankee Stadium. White also fared well in the postseason, particularly in League Championship Series play. No less an authority than Bill James (who is ironically now a Boston Red Sox employee) has become one of White’s biggest champions, going so far as to claim that White was a better ballplayer than his Red Sox’ left field counterpart, Jim Rice. That’s especially noteworthy given that Rice undergoes an annual dalliance with the BBWAA, which has come within a whisker of electing him to the Hall of Fame. Rice is expected to win election next January, while White fell off the writers’ ballot after one inglorious campaign in 1985. White received no votes (while far lesser players like Don Kessinger and Jesus Alou garnered two and one, respectively), thereby dropping off the ballot immediately.

Now I don’t mean to carry the appreciation of White too far. Personally, I’ve never completely swallowed the comparisons with Rice. Rice’s lifetime on-base percentage was only eight points less than White’s, while his slugging percentage was light years better. The measure of ballpark effects is overrated here, too. While Rice certainly had an advantage hitting at Fenway Park, let’s remember that Yankee Stadium’s reputation as a pitcher’s park for much of the sixties and early seventies was overstated because of just how poor the Yankees’ offense was during those in-between years. Lineups overrun by players like Bobby Cox, Ron Woods, Jerry Kenney, and Celerino Sanchez tended to suppress the run-scoring totals at the Stadium. And then there was the matter of White’s arm, which might have been worse than that of Bernie Williams. White tended to throw "parachutes"—long, looping throws with a high arc—giving opposition baserunners an opportunity to take extra bases on balls hit to left field.

White’s popgun arm and lack of raw power will certainly keep him out of the Hall of Fame, but that shouldn’t detract from his importance to the Yankee franchise. He was a vital element in the Yankees’ pennant-winning run from 1976 to 1978. In the 1976 League Championship Series, White accumulated five walks, tying a major league record. In the 1978 LCS, White hit .313, once again tormenting the opposition Royals, and blasted a game-winning home run in the clinching sixth game. He then went on to hit a home run and drive in four runs against the Dodgers in the World Series, as the Yankees staked claim to their second straight world championship. Additionally, White supplied the Yankees with a critical off-the-field attribute. On a team filled with combustible, high-octane personalities, White provided some gentlemanly stability and a calming, even-keeled presence. Well liked and respected by his teammates, White never gave anyone on the Yankees reason to criticize him in the media, or challenge him to a fight in the dugout.

For those reasons, along with that delightful pigeon-toed stance, Roy White no longer deserves to be the forgotten Yankee.

Bruce Markusen is the author of seven books on baseball, but none about the Yankees. Please send any Yankee-related book deal offers to bmarkusen@stny.rr.com.