As I’ve watched the Yankees throughout the first half of 2008, I’ve come to the conclusion that they could use someone like Cliff Johnson. Of course, Cliff is 60 years old now, and probably not in condition to bend his knees behind the plate or swing a bat in anger. In actuality, I’m referring to the Cliff Johnson of roughly 30 years ago, when he gave the Yankees the kind of right-handed hitting and bench strength that this year’s Yankees so badly require.

For much of the 1970s, the Yankees tried to acquire some extra right-handed hitting. In 1973, they purchased Jim Ray Hart, who lasted only a calendar year as a platoon DH before it became obvious that he was washed up, in part because of his problems with drinking. After the season, the Bombers acquired switch-hitting Bill “Suds” Sudakis from the Texas Rangers. Sudakis succeeded in one thing—making headlines when he brawled with Sweet Lou Piniella during a road trip in Milwaukee. In the spring of 1974, the Yankees acquired Walt “No Neck” Williams as part of a larger deal with the White Sox. Williams made a splash, but mostly because of his unusual head-and-shoulders appearance. Later that season, the Yankees made a last-minute deal for Alex Johnson, followed by a December transaction that brought in Bob Oliver from Baltimore. Both players had once been highly productive; both players failed to last a full season at Shea Stadium.

In the spring of 1976, the Yankees gave Tommy Davis, one of my favorites, a look-see. He never made it into a game, released on the eve of Opening Day. Then came another favorite, Cesar Tovar, who was also one of Yankee manager Billy Martin’s preferred pets. Tovar could play anywhere, but unfortunately couldn’t hit anything—at least not any more. After the season, the Yankees appeared to have hit the jackpot with the perennially underrated Jimmy Wynn. But “The Toy Cannon” had little fodder remaining; he batted .143 in 77 at-bats and received the boot.

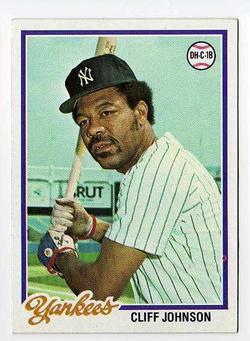

Still searching for a right-handed role-playing bat in 1977, the Yankees then pulled the trigger on a deal just before the June 15th deadline. General manager Gabe Paul sent three extraneous minor leaguers—first baseman Dave Bergman, infielder Mike Fischlin, and lefty Randy Niemann—to the Houston Astros. In exchange, the Yankees received what they desperately needed on two different counts—a right-handed bat and a backup catcher. Cliff Johnson had finally come to town.

Coming to bat 142 times for the ’77 Yankees, Johnson provided exactly what Martin and Gabe Paul wanted. Heathcliff batted .296 with 12 home runs; more significantly, he slugged .606 and compiled a .405 on-base percentage. When the opponent threw a left-hander at the Yankees, Martin rightly found a place for Johnson in the lineup. Granted, Johnson wasn’t much of a catcher—at six-four and 240 pounds, he was clumsy and owned hands of stone—but he could play the position in short doses. He could also fill in at first base and the outfield corners (though he never did play in left or right field during his Yankee days). Most critically, Johnson could hit—swinging the bat better than any backup catcher the Yankees had featured since the salad days of Johnny Blanchard.

Johnson became an important part of the Yankees’ second-half surge that summer. He also devoured the Kansas City Royals’ pitching staff in the ALCS. In 16 at-bats, Johnson delivered six hits, swatted one home run, and slugged .733, helping the Yankees clinched the American League pennant in a wild five-game series. As far as June 15th trade deadline deals were concerned, Johnson had become one of the best mid-season acquisitions in Yankee history.

The 1977 season turned out to be the peak of Johnson’s career in pinstripes. In 1978, the bottom fell out of his game. Losing his stroke in his continuing role as a spare part, Johnson batted .184 with only six home runs in 174 at-bats. He became a nonentity in the postseason, going hitless in three at-bats against the Royals and Los Angeles Dodgers. The following spring, Johnson became a liability in the clubhouse. In late April, he took offense at some playful ribbing from Goose Gossage and gave the Yankees’ relief ace a slap of his hand. That led to a full-scale wrestling match—and a tumble into the bathroom toilet stalls. Johnson escaped unharmed, but the Goose endured a torn ligament in his pitching thumb. He would miss the next three months of the 1979 season, which turned into a lost journey for the Yankees.

With that one incident, Johnson signed his Yankee death notice. Within two months, he was gone—shipped off to the Cleveland Indians in a bad deadline deal for a mediocre left-hander named Don Hood. (Hood was better than Billy Traber, though. Hood could have helped the 2008 Yankees, too.) Johnson would eventually resuscitate his career as a power-hitting DH and occasional catcher, and would later become a highly effective pinch-hitter for the Toronto Blue Jays, but his days as a Yankee had come to an ungracious end.

I wish it had turned out different for Johnson. I’ve always liked journeyman ballplayers who aren’t stars, but are still useful players—just like Johnson was. I remember how Phil Rizzuto used to playfully refer to him as “Heathcliff.” That wasn’t his real first name (it’s Clifford), just a clever-sounding nickname. Others called him “Topcat,” for reasons that remain a mystery to me to this day. Not surprisingly, Gossage described Johnson as a “lazy and worthless piece of crap” in his 2000 autobiography, ripping into Johnson for his tendency toward “moping around,” around the bullpen, where he allegedly refused to warm up pitchers from time to time. I read those descriptions with some sadness, mostly because they didn’t jell with the image I had of Johnson as a mammoth man who spoke softly but carried a big bat—literally.

Come back, Cliff Johnson. We could use someone like you in 2008.

Bruce Markusen writes “Cooperstown Confidential” for MLBlogs at MLB.com.