In 1975, the Yankees played the last of two seasons in which they called Shea Stadium their home. Reggie Jackson had not yet arrived, nor had Willie Randolph. Roy White, while still a good player, was past his peak. Thurman Munson was beginning to establish himself as a star, but was still one year away from being recognized as the American League MVP. So who was the Yankees’ best player during that final season at Shea? It had to have been the man that few remember as a Yankee. He was the same man that younger fans now remember mostly as the father of Barry Bonds.

In 1975, the Yankees played the last of two seasons in which they called Shea Stadium their home. Reggie Jackson had not yet arrived, nor had Willie Randolph. Roy White, while still a good player, was past his peak. Thurman Munson was beginning to establish himself as a star, but was still one year away from being recognized as the American League MVP. So who was the Yankees’ best player during that final season at Shea? It had to have been the man that few remember as a Yankee. He was the same man that younger fans now remember mostly as the father of Barry Bonds.

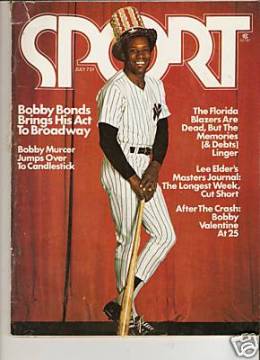

How talented was Bobby Bonds? He was the most gifted outfielder the Yankees had during the entire decade of the 1970s, more talented than even Jackson, a future Hall of Famer. A 30-30 man with game-breaking speed, Bonds was much faster, could play center field with skill and precision, and had just as much power. Jackson was physically better only in one respect; he had a stronger throwing arm, and even that capability had diminished by the time he joined the Yankees in 1977. Bonds was certainly more talented than the man for whom he was traded to New York after the 1974 season, Bobby Murcer. Bonds had more power, speed, and range, and drew more walks. Murcer made better contact, but that was about it. Clearly, Bonds was better.

Yankee fans didn’t care that Bonds had more physical ability and was capable of putting up superior numbers. They bemoaned the loss of the beloved Murcer, whose down-home personality, smooth left-handed swing, and embodiment of the little man made him an icon at Yankee Stadium. The Yankees could have traded Murcer for Hank Aaron or Frank Robinson and still felt a backlash from fans who believed the front office had been disloyal to a favorite son.

In spite of the hostile welcoming party waiting for him at the Shea Stadium turnstiles, Bonds played well during the first half of the 1975 season. He picked up enough votes in the fan balloting to win a spot as a starter on the American League All-Star team. His only adversity occurred in June, when he missed a week’s worth of games because of a strained knee. But then came a larger obstacle, one that arrived in the form of a mid-season managerial change.

On August 2, the Yankees fired the placid Bill Virdon (whom Bonds enjoyed playing for) and replaced him with the temperamental Billy Martin. Surely someone in Yankeeland realized that the new skipper could not coexist peaceably with Bonds. Martin brought with him a reputation for moodiness and mayhem; at every managerial stop, he constructed a virtual doghouse, in which he placed players who made mental mistakes, didn’t hustle, or challenged his authority. Bonds, in spite of his wealth of talent, had developed a reputation as a careless baserunner and occasional loafer in the outfield, where he was known to miss a cutoff man or three during his day. Martin liked players who scrapped, not players who sometimes overlooked the "little things," the way that Bonds did. And then there was the off-the-field factor. Both Bonds and Martin liked to drink—and drink heavily. Given such a combustible formula, the two men were bound to clash.

The inevitable collision occurred on August 17, during a road trip in Kansas City. The Yankees took an early 3-1 lead, but the Royals stormed back to tie the game in the bottom of the fifth against Jim "Catfish" Hunter. In the seventh inning, Kansas City’s Al Cowens hit a fly ball to deep center field. Bonds failed to track down the long drive, instead crossing paths with Yankee right fielder Lou Piniella. Cowens ended up with a triple, enraging Martin, who believed that Bonds could have made the catch with a more determined effort. Furious with Bonds, Martin sent backup outfielder Rick Bladt into the game, replacing his star center fielder. The move clearly upset Bonds, who refrained from directly confronting Martin. Instead, Bonds and Martin spent the rest of the game glaring at each other in the Yankee dugout.

The Yankees went on to lose the game, which resulted in Martin overturning the postgame spread during a clubhouse meltdown. Coincidentally or not, Bonds played the next game in right field, with former Orioles speedster Rich Coggins replacing him in center. Bonds then returned to center field the next day, but his relationship with Martin had been irreparably frayed.

Problems with Martin aside, Bonds led the Yankees in both on-base percentage and slugging in 1975. He again achieved the 30-30 milestone, something he had done twice during his days in San Francisco. He finished fourth in the American League in home runs, overcoming the difficult dimensions of Shea Stadium, known as a graveyard to most mortal power hitters. Given his ample on-field achievements, Bonds should have remained in pinstripes for years, becoming a player the Yankees could build around as they prepared to move closer to contention while simultaneously moving into the remodeled Yankee Stadium.

It didn’t happen. Yankees general manager Gabe Paul, knowing about the friction between his manager and his hard-living star player, shopped the 29-year-old Bonds until he received an offer he couldn’t refuse. The Angels ponied up Mickey Rivers, the fastest man in baseball, along with a young workhorse right-hander named Ed Figueroa. Casual fans, many of whom knew little about Figueroa, wondered why the Yankees had seemingly acquired so little for a star talent like Bonds. Less interested in name value than he was in fortifying the team’s starting rotation, Paul knew exactly what he was doing. Figueroa would emerge as the team’s number-two starter, behind first Catfish Hunter and then Ron Guidry. Rivers, while not nearly the ballplayer that Bonds was, would bring energy to the lineup and color to the clubhouse.

It would have been fun to watch Bonds and Reggie Jackson play together in the same outfield, but the situation turned out nicely for the Yankees. Figueroa and Rivers became key contributors, helping the franchise claim three American League pennants and two world championships in the span of three seasons. Unfortunately, Bonds’ fate turned wearisome and cruel. Averaging about a team per season, Bonds bounced from the Angels to the White Sox to the Rangers to the Indians before flopping with the Cardinals and Cubs. Worn down by too much drinking and too many cigarettes, Bonds aged badly while residing in the fast lane. By the age of 33, his days as a regular had come to an end. By the age of 35, his days as a major leaguer were over.

Twenty-two years later, Bonds’ life ended, his 57-year-old body victimized by a brain tumor and cancer in his kidneys. In so many ways, I wish it had turned out differently for Bobby Bonds.