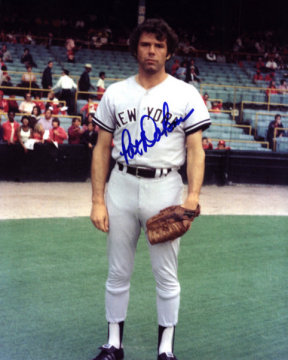

Right from the get-go, I have to admit I’m cheating a bit with this article, the last in my series on the "relics" of Shea Stadium. The previous three articles profiled Yankees of the 1970s who never called Yankee Stadium home, since their careers coincided only with the Shea Stadium seasons of 1974 and ’75. In actuality, Pat Dobson did pitch for the Yankees during the second half of the ’73 season, the final campaign at the "old" Yankee Stadium. But I’m willing to make an exception for "Dobber." He’s worth it.

I never met Dobson, but I always enjoyed reading articles that quoted him, especially from his days as a scout. Known as a funny free spirit during his playing days, Dobson became known for the strange vernacular he invented. He called curve balls "yakkers." He referred to liquor as "oil." And he called a big game a "bogart." Many of his invented terms were adopted by his teammate in Cleveland, Dennis Eckersley, who made such slang famous later in his career.

After his playing days, Dobson became a legendary storyteller and an incisively honest assessor of major league talent, both good and bad. Largely employed as an advance major league scout, Dobson did good work for a number of years with the Rockies and the Giants, who benefited from the opinions he offered based on his years of experience.

Dobson also happened to be a very good pitcher, a legitimate No. 3 starter for some excellent postseason teams of the 1970s. In today’s game, a younger Dobson would have merited a four-year contract worth $40 million, maybe more, on the open market. He was that good.

Dobson is best remembered for being one of four 20-game winners on the 1971 Orioles, but he was previously an important part of a World Championship bullpen. He pitched in long relief for the 1968 Tigers, succeeding the likes of Denny McLain and Mickey Lolich on those rare occasions when those workhorses didn’t last through the eighth or ninth innings. Although the Tigers’ starters accumulated a ton of innings in 1968, Dobson did pitch effectively when called upon. He posted a 2.66 ERA in 125 innings, finished second on the team with seven saves, and even started 10 games as a spot starter. Dobson filled a role that is rarely seen in baseball today: that of the utility pitcher who can close, pitch middle relief, or start from time to time. In short, he was an early day version of two other former Yankees known for their versatility, Dick Tidrow and Ramiro Mendoza.

After trying to find a more defined niche with the Tigers and the Padres in the late 1960s, Dobson blossomed fully under the tutelage of Hall of Fame manager Earl Weaver and pitching coach George Bamberger with the Orioles. At the time that Dobson joined the Orioles, he featured five pitches that he threw from several different angles and windups. Weaver simplified his approach, encouraging Dobson to adopt a single windup and concentrate on using his two or three best pitches. The approach worked; Dobson not only won 20 games in 1971, but also remained an effective starter in 1972 before the Orioles foolishly traded him to the Braves as part of the ill-fated Earl Williams deal. In the middle of his first season in Atlanta, the Braves gave up on him (as if they had too much pitching to spare), sending him to the Yankees for a package of four minor leaguers—first baseman Frank Tepedino, minor league outfielder Wayne Nordhagen, and pitching prospects Dave Cheadle and Alan Closter. None would have much impact with the Braves. Score another one for underrated Yankee general manager Gabe Paul.

Just as he did with the Orioles, Dobson became a workhorse in pinstripes. In 1974, he totaled 285 innings, won 19 games, completed 12, and posted a 3.07 ERA. His performance fell off in 1975, perhaps an effect of overwork, but he still pitched over 200 innings and contributed 11 wins to the cause. Now 33 years of age and on the downhill side, Dobson became expendable during the winter, when the Yankees traded him to the Indians for another favorite, Oscar Gamble.

As a pitcher, Dobson left a lasting impression with one of his featured pitches. He threw a phenomenal overhand curve ball, which he couldn’t throw for strikes in Detroit but began to refine with more precision in Baltimore and maintained in New York. It wasn’t as good as that of one of his contemporaries, the incomparable Bert Blyleven, but it was only a notch below. (Think of Neil Allen or Rod Scurry, two former Yankees from the late 1980s, in terms of similarly devastating curve balls.) If Dobson had ever developed another pitch with remotely the same effectiveness as his curve, he would have likely been a 200-game winner and a borderline Hall of Fame candidate.

After his playing days, Dobson remained highly successful. He became a respected pitching coach for the Brewers, Padres, Royals, and Orioles —he could diagnose a flawed pitching delivery almost immediately—and then a trusted scout and front office advisor for the Giants. Here’s what I really liked about Dobson: as a scout, he was outspoken to colorful extremes. He gave honest opinions to the media, sometimes so brutally forthright that he put himself into the line of fire. A few years ago, a USA Today Baseball Weekly article quoted Dobson liberally, featuring some of his typically frank assessments of various players, especially of opposing players. These were the kinds of comments you often see in print, only they’re attributed to an "unnamed" or "anonymous" scout. Not so with Dobson, who believed in expressing his opinions freely and openly when asked. The Giants, his employers, reacted angrily and reprimanded him. As I recall, they came close to firing him. Thankfully, they didn’t. A few years later, they actually promoted him, making him an assistant to GM Brian Sabean.

In November of 2006, while still working for the Giants, Dobson learned that he was suffering from leukemia. Exactly one day after hearing his diagnosis, he died in a San Diego hospital. His death was tragic on a number of levels. He was still working, still only 64 years old. He still had plenty of stories to tell. If he had lived a little longer, he probably would have expressed a colorful opinion or two about the leukemia that had taken hold of his body.

Fortunately, Dobson extracted the most out of his 64 years. "He made his life baseball," Earl Weaver said of his onetime pitcher, "and enjoyed every minute of it."

Bruce Markusen writes "Cooperstown Confidential" for MLB.com.