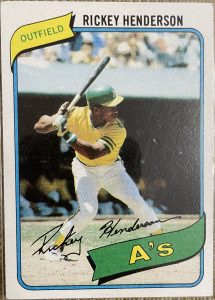

The greatness of Rickey Henderson was undeniable, even if it took baseball people longer than you’d think to recognize that Rickey could do more than just run. The Man of Steal burst on the scene with the Oakland Athletics not just by stealing more bases than anyone had before him, but by stealing more bases than anyone had thought possible. He bent reality in the way that only the greatest players can, but because people are the way they are, his early achievements were viewed from a deficit perspective.

Critics complained that he was selfish, that stolen bases in the ninth inning with his team down by four only tarnished the record, or they claimed that he was incomplete player, never mind the fact that at just 23 years old when he stole a preposterous 130 bases in that 1982 season, Rickey also scored 119 runs and led the league with 116 walks. The year before he had won a Gold Glove.

His greatest years, however, were still ahead of him. After being traded to the Yankees prior to the 1985 season, he thrived on the biggest stage in the game, becoming the only player in our lifetime to score more runs (146) than games played (143) while stealing 80 bases and slashing .314/.419/.516 only to lose the MVP to teammate Don Mattingly. Rickey would eventually get his MVP five years later after his return to Oakland when he stole 65 bases while hitting 28 home runs with a staggering 1.016 OPS.

How good was he? Without question, he was the greatest leadoff hitter of all-time. Bill James, the godfather of statistical analysis, once said that Rickey was so good that if you could split him into two players, you’d still have two Hall of Famers. (Here’s a discussion about that.) To that point, if we disregard his slugging numbers and his 3,055 career hits and focus on the true through-line of his career, the stolen base, the numbers are mind boggling.

- His 1,406 career stolen bases is just one steal shy of being a full 50% better than Lou Brock’s second place total of 938. For perspective on that, the top four active stolen base leaders (Starling Marte, José Altuve, Trea Turner, and José Ramírez) have a total of 1,480 steals.

- During the twelve-year stretch from 1980-1991, Henderson led baseball in steals eleven times.

- Seven years after the end of that run, in 1998, Rickey again led baseball with 66 stolen bases for the San Diego Padres at the age of 39.

The statistics eventually become mind-numbing, but the true measure of any legend lies in the mythology that grows up around them. Did Rickey really frame his first million dollar check rather than cash it? (Yes, but still got the money.) Did he really tell Jon Olerud that he had once had a teammate who also wore his helmet in the field, forgetting that the former teammate was actually Jon Olerud? (No, but it’s a good story.)

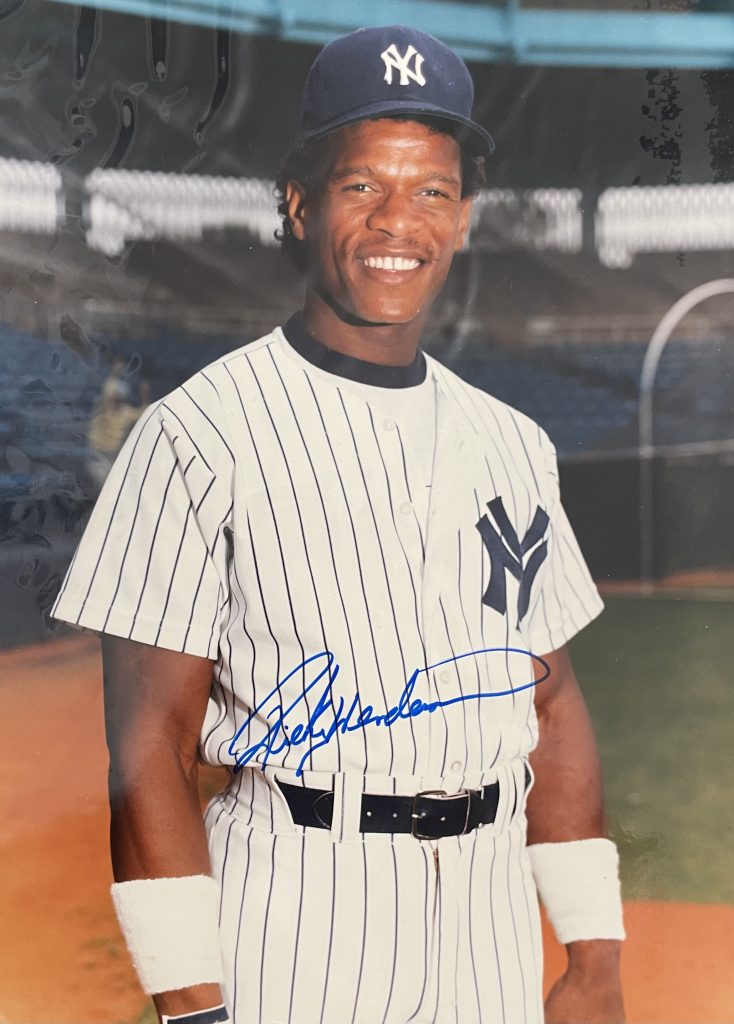

Everyone in Rickey’s orbit had a good story to tell, even me. I collected baseball cards growing up, and when the hobby exploded in the 1980s, I began going to card shows, not just to grow my collection but to collect autographs. Rickey Henderson was a guest at a card convention in the spring of 1986 during his second year with the Yankees, so I drove down to the freeway so I could pay ten or twenty dollars for the autograph of one my favorite players.

Most of the players who appeared at events like this simply churned out one signature after another, earning their appearance fee by mindlessly repeating autographs on balls, bats, and photos for an hour or two. They were often bored or disinterested, sometimes surly and dismissive. Rickey was none of these things. He had far too much energy to be trapped in a folding chair behind a plastic table, and his eyes darted around the room, taking in everything, but connecting with no one.

When I finally made my way to the front of the line, Rickey’s eyes stopped on mine. We were in Orange County in the mid ’80s. If the world outside that hotel was predominantly white, that said nothing about the demographics of the hall we were in that afternoon. It’s likely that Rickey and I were the only two Black people in the room, and Rickey’s darting eyes were keenly aware of that. He took one look at me, extended his hand and said — and I will never forget this — “What’s happenin, soul brother?”

I was sixteen years old, filled with the typical insecurities of adolescence, but because I had spent my life growing up in places like Naperville, Illinois, and Irvine, California, I had never been comfortable in my own skin simply because that skin wasn’t the same color as the kids at school or the people in my neighborhoods. I was different, and it would be years before that discomfort would go away.

Rickey could never have known any of this, but he saw me. I didn’t quite know what to make of it in that moment, but it’s something that’s stayed with me in the three decades since. When I heard the news that Rickey had passed, appropriately dying the same year his Oakland A’s did, I eventually thought about the afternoon in Oakland when two friends and I sat in the right field bleachers and watched Rickey grab his 939th stolen base, but my first reaction was to think back to that day at the card show when a legend reached out and connected with me.