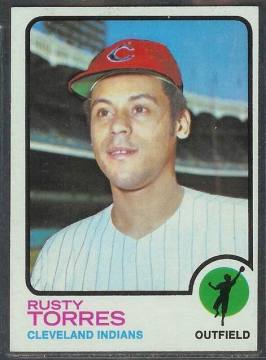

If you were born after 1965, you probably don’t have many memories of Rusty Torres in a Yankees uniform. A lean, switch-hitting outfielder in the Roy White mold, Torres played for the Yankees in 1971 and ’72 before being packaged to the Indians as part of the deal that brought Graig Nettles to New York. Torres never became a regular, instead settling for a journeyman nine-year career that included stops with the Angels, White Sox, and Royals.

In contrast to some pedestrian players, Torres’ story is far more interesting than that of a backup. After signing with the Yankees’ organization, the Puerto Rican-born Torres became an unofficial liaison between Yankees management and Latino players. Having spent much of his childhood in Brooklyn, Torres became fluent in English, a skill that helped him serve as an interpreter for the Yankees’ young Latino players and prospects. For this, he received no extra pay, and seemingly no extra consideration from manager Ralph Houk when it came to playing time. On one occasion, Torres challenged Houk to play him every day for 20 consecutive games; if Torres flopped, he would pack his bags and head back to the minor leagues. Houk refused the offer.

Although Torres continually pined for playing time during his career, he did have the bizarre and unprecedented distinction of actually playing in three forfeited games during the 1970s. (There were a total of four forfeited games that decade, so Rusty made it for three out of the four.) Each time, he witnessed spectacles rarely seen in ballparks today, all while managing to escape tangible harm from unruly fans.

Now retired from baseball for 27 years, Rosendo "Rusty" Torres serves as the president of Winning Beyond Winning, a non-profit group that attempts to educate and counsel young athletes. Last weekend, I met Torres at the Museum of the City of New York, where we both participated in a panel discussing the changing roles of Latinos in baseball. Engaging, charming, and thoughtful, Rusty took some time to talk to me after the program. Here is part of our discussion.

Markusen: I love nicknames. Where did Rusty come from? How did that start?

Torres: I came to Brooklyn in 1955, when I was seven years old. When I was young, I had blond hair and blond eyebrows; my father was an Anglican Spaniard. I have the African side from my mom, who is half Caribbean Indian and half African American. The color of my skin was like gold. Then we moved to another neighborhood in Brooklyn, one that had a lot of kids. It was always packed outside. I went outside, and they’re checking me out real good, and they asked me my name. I said my name is Junior. They said, "No, no, no, we have plenty of Juniors." They said, "What’s your first name?" I told them it was Rosendo. They said I needed a nickname. I didn’t really understand this thing with nicknames. One guy called me Rosy, not only that, he said, "You look Rosy." I told my dad my new name. He said, "No, you’re not a Rosy, you’re a Rosendo, Rosy—that’s a girl’s name." So I went back outside. There used to be this thing that announcers would say, "He swings like a rusty gate." Here I am playing stickball, I couldn’t play, I was only about eight years old, I was horrible. They gave me a bat, I couldn’t hit. One of the guys, whose name was Manuel, looks at me and says, "Hey, Rusty, Rusty. We’re going to call you Rusty. Not only that, but you are rusty, you swing like a rusty gate, and you look rusty. And you know what, that has stuck to this day. Years later, my whole family calls me Rusty. Junior left, Rosendo left, and Rusty took over.

Markusen: As you look back, do you have any regrets over the fact that maybe people didn’t know about your Latino background because they didn’t call you Rosendo? Do you regret that you didn’t ask people to call you by your real name?

Torres: Well, believe it or not, after I was with the Yankees and went through the experience of being a babysitter for the [Latino] Yankees all those years and being an interpreter for those Spanish-speaking ballplayers, when I was traded to Cleveland, I kind of rebelled against the system.

When I got traded to Cleveland, I was traded for [Graig] Nettles in the winter of ‘72, and then got to Cleveland in ’73, and they called me Rusty. They called me Rusty. I was sitting on the bench still and I got angry. I got angry about the situation and I rebelled against the whole system and made them call me Rosendo. Aspromonte, who was the manager, Ken Aspromonte, came up to me and said, "Why did you tell them to stop calling you Rusty. Rusty Torres, that’s a great baseball name." I said, if I can’t play regularly in the major leagues, and I’m not good enough to play in the major leagues everyday, I want to be called by my [real] name. At least I have my heritage. And my name that I can use. So they started calling me Rosendo.

And then years later, I gave up fighting it. I just withdrew. I still fought management, insisting about being called Rosendo, but I withdrew. I withdrew to the dugout.

Markusen: You played in three forfeited games during the 1970s, the last game for the Washington Senators in ‘71, Ten-Cent Beer Night—which was a disaster—and Disco Demolition. Talk about that, playing in those three forfeited games. That’s an incredible coincidence.

Torres: (laughing) That’s my claim to fame in baseball. A lot of people ask me about that. I came up in 1971; that was when I was called up from the Yankee farm team. We were going to Washington and I really didn’t know what was going on even though all the players were talking about it. It didn’t really hit me [about the Senators’ impending move to Texas]. What I was thinking about was that Ted Williams was the manager and that the Senators had about ten minor league players who had played against me. And I was dying to see them. I had my mind completely off the topic of the team moving.

So I go to the stadium. I used to go in early to run because I was really enthusiastic about running. Plus, I was in Washington, it was exciting. All of a sudden I see these people dragging this huge thing, I couldn’t tell what it was, but it looked like a huge dummy. They were pulling it by the neck by a big rope. I’m looking and running, and I see this people pulling this thing all the way down the right field line. And all of a sudden, they start pulling it up toward the upper deck. It’s going up, first deck, second deck. I looked and it was a big gigantic dummy! Right on its chest, it had a sign that says, Short—that was the name of the owner of the team—"Short Sucks." So then they had it up by the neck with a noose and everything. I’m going, "What the heck is going on?"

All of a sudden the game starts, we’re playing the game, and people are shouting, and I’m still not into it. Jerry Kenney, who was traded with me to Cleveland, said to me, "You better hold onto your hat. There’s something going to happen here." So I said, "What’s going to happen?"

It just so happens that I was supposed to hit [in the ninth inning]. Bobby Murcer hits a ground ball. He gets thrown at first. They thought it was three outs. It was only two outs. And they rushed us! They rushed the field. They took dirt. People were taking dirt, taking the bases. They were tearing up the seats. It was unbelievable. That was a real scary experience.

Thankfully, none of us got hurt.

The author of eight books on baseball, Bruce Markusen writes "Cooperstown Confidential" for MLB.com. He can be reached at bmark@telenet.net.