Every few years, hair becomes a source of controversy in baseball. Yes, that’s right, hair. Earlier this season, Nationals first baseman Dmitri Young grew his Afro so large and curly that manager Manny Acta finally asked him to reach for a pair of scissors. Not wanting to upset his manager—especially after showing up to spring training at a robust 298 pounds—Young complied. (The loss of hair may have removed a pound or two from his weight, too.) In the meantime, Cardinals rookie outfielder Brian Barton continues to earn attention for his reggae style dreadlocks, which have given him a unique look among major leaguers. Barton’s hair, at least in some quarters, has gained him more notoriety than his impressive play—and the Indians’ ill-fated decision to leave him unprotected in last winter’s Rule 5 draft.

Barton and Young are not the first players to create a tempest in a teapot when it comes to the topic of hair. Here are a few other hair-related controversies that have spiced up the game off the field over the past 40 years.

Rey Sanchez, 2003: As the Mets found themselves enduring a blowout loss to the Cardinals in late April, Rey-Rey decided to spend part of the game in the clubhouse getting a hair cut. Sanchez reportedly left the Mets’ dugout in the fifth inning, sat down for his hair appointment, and later returned to the bench before being summoned as a pinch-hitter. Sanchez repeatedly denied receiving the infamous haircut during the game, but none of the other Mets supported his denial. Not surprisingly, Sanchez didn’t last the season with the Mets, in part because they wanted to make room for Jose Reyes. But the haircut may have played a role in his hairy—I mean hasty—departure.

Don Mattingly, 1991: We don’t usually associate "Donnie Baseball" with controversy, but in mid-August of 1991, Mattingly was benched by manager Carl "Stump" Merrill for his refusal to cut his lengthening hair. Mattingly’s locks, which came dangerously close to his collar, apparently upset George Steinbrenner, who allegedly told Merrill to pass the message of discontent along to the Yankees’ All-Star first baseman. In addition, the Yankees hit Mattingly with a $250 fine and told him that $100 would be added to the total for each day his hair remained "over the line." While Mattingly became the focus of the story, three other Yankees (catcher Matt Nokes and pitchers Pascual Perez and Steve "The Burglar" Farr) were also warned to get their hair trimmed—pronto. They did, and so did Mattingly. Yet, the story didn’t end there. After Mattingly sat down for his haircut, a New York radio station auctioned off the shorn hair for a charitable cause. A city policeman ended up submitting the winning bid at $3,000, and as a way of insuring that he was getting the actual goods, received a certificate of authenticity—signed by Mattingly, Merrill, and Yankee coach Carl "Hawk" Taylor, who enjoyed a one-day career as the barber and did the actual cutting of Mattingly’s hair. Only in New York.

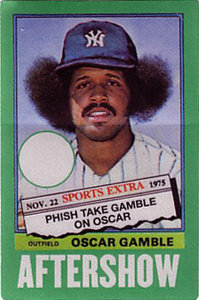

Oscar Gamble, 1976: "The Big O" owned baseball’s biggest Afro in the 1970s and likely the largest in all of baseball history. (In fact, Young may have been closing in on Gamble’s record before Acta put him in touch with a barber.) The Indians allowed Gamble to keep his Afro, which stretched beyond the normal dimensions of a batting helmet and sometimes made him look like he had Mickey Mouse ears, or in one particular photo, gave him a frightening hairstyle that appeared eerily similar to that of Princess Leia in Star Wars. Yet, Gamble’s hair became a real problem when he was traded by the Indians to the Yankees prior to the 1976 season. George Steinbrenner didn’t like Gamble’s hair protruding from both sides of his helmet and told his public relations director, Marty Appel, to order Oscar to remove the excess bulk. Appel arranged the now famous "Hair Cut Heard Round The World," which cost a cool $33 (a tidy sum in the mid-1970s economy), allowing Gamble to begin his Yankee career in appropriately conservative style.

Dock Ellis, 1973: At times, the behavior of the Pirates’ right-hander bordered on the bizarre. In perhaps his most celebrated incident—other than allegedly pitching a no-hitter under the influence of LSD, that is—Ellis walked out onto the field before a 1973 game against the Cubs wearing a head full of hair curlers. "I think the big thing with him when he come out on Wrigley Field with the hair curlers," recalled Pirates third baseman and teammate Richie Hebner, "is that when he did that, other than surprising a lot of people at Wrigley Field, it surprised a lot of guys on the Pirate team. When I saw it, I said, ‘What the hell is this?’ " Commissioner Bowie Kuhn offered a similar reaction and reportedly conveyed his unhappiness over the hair curler episode to Bill Virdon, the Pirates’ manager. Relaying the commissioner’s message, Virdon told Ellis to cease his practice of wearing the curlers on the field. "Look, Dock," Virdon said, "I don’t care what you wear, but the front office doesn’t like it, the umpires don’t like it, and if you’re not careful, you’re going to get fined."Another Pirate, slugging first baseman Bob Robertson, recalled his own involvement in the hair curler episode. "[The manager] comes to me and says, ‘Go out and ask Dock why he’s got those curlers in his hair?’ So I did. And I think, if I can remember correctly, Dock said, ‘That’s me. Those are my curls.’ And that was about it. So I went back and told [Virdon] and that was the end of that stuff." Much to Virdon’s delight, Ellis eventually backed off on his preference for curls and didn’t wear the hair curlers on the field again, sparing the Pirates the Wrath of Kuhn.

Reggie Jackson, 1972: Jackson, the most prominent player on the Oakland A’s, reported to spring training replete with a fully-grown mustache, the origins of which had begun to sprout during the 1971 American League Championship Series. To the surprise of his teammates, Jackson had used part of his off-season to allow the mustache to reach a fuller bloom. In addition, Jackson bragged to teammates that he would not only wear the mustache, but possibly a beard, come Opening Day.Such pronouncements would have hardly created a ripple in later years, when players would freely make bold fashion statements with mustaches and goatees, and routinely wear previously disdained accessories like earrings. But this was 1972, still a conservative time within the sport, in stark contrast to the rebellious attitudes of younger generations throughout the country. Given that no major league player had been documented wearing a mustache in the regular season since Wally Schang of the Philadelphia A’s in 1914, Jackson’s pronouncements made major news in 1972. (There is some dispute about this; some sources report that Dick Allen and Felipe Alou wore mustaches in 1970, or two years before Jackson, but I haven’t been able to prove this one way or the other.)

Not surprisingly, Jackson’s mustachioed look quickly cornered the attention of Oakland owner Charlie Finley. Attempting a bit of reverse psychology, Finley encouraged several of his players to grow mustaches, so that Jackson would no longer stand out as a rebel and maverick. Once Jackson saw the other players join in, he would then shave his mustache.

That was the thinking—at least in theory. Instead of making Jackson feel less individualistic, thus prompting him to adopt his previously clean-shaven look, the strategy had a reverse and unexpected effect on Finley. He liked the new look of the A’s, with his players wild, hairy and mustachioed, in contrast to the staid look of the other 23 teams. Finley arranged for "Mustache Day," promising $300 bonuses to each player who grew facial hair above the lip for the promotion. Baseball’s longstanding hairless trend had officially come to an end.

Joe Pepitone, 1960s: Flaky and well-traveled during his major league career, the former Yankee, Cub, Astro, and Brave became a baseball pioneer of sorts when he became the first man to bring a blow dryer into a major league clubhouse. Two of his teammates, Jim Bouton and Fritz Peterson, once filled the blow dryer with talcum powder, which left Pepitone with a replica George Washington powdered wig. Ever the pioneer, Pepitone also became the first major leaguer to use hairspray in the clubhouse.

Pepi’s trendsetting maneuvers struck some as ironic, given that he consistently wore hairpieces over his balding pate. In fact, Pepitone used two pieces; he sported a larger wig for social settings and a smaller one—his "gamer"—that snugly fit under his cap and helmet at the ballpark. Both pieces, by the way, looked hideous.

Other than their involvement in these hair-raising episodes, you might notice that all six of these players (Sanchez through Pepitone) have something in common. They all, at one time for another, played for the Yankees—the same Yankees who have never allowed their players to wear beards. As Cosmo Kramer might say, "That’s weird."

Bruce Markusen, the author of seven baseball books, writes "Cooperstown Confidential" at http://www.bruce.mlblogs.com.