Dick Tidrow wouldn’t fit into today’s game. In an era in which pitchers have become so specialized—there are set-up men, lefty specialists, innings eaters, one-inning closers, five-inning starters, crossover relievers, and never shall any of these categories overlap—no one would fully appreciate Tidrow’s value. That’s because a large part of Tidrow’s value was the actual versatility he brought to the pitching table. He could pitch set-up relief, serve as a long man, close out games occasionally, and fill in as a starter on a moment’s notice. He could perform all of those roles effectively, sometimes within a span of about two weeks, making him one of the most subtle but vital contributors to the Yankees’ mini-dynasty of 1976 to 1978.

Yet, Tidrow didn’t become a bastion of versatility overnight. Bursting onto the major league scene in 1972, Tidrow emerged as a durable right-handed starter for the rebuilding Cleveland Indians. Pitching only occasionally in relief, Tidrow made 74 starts for the Indians in 1972 and ’73, logging over 500 innings in the process. As the Indians’ number-two starter (behind Gaylord Perry), the young workhorse pitched well enough in 1972 to earn The Sporting News’ American League Rookie of the Year award. After a poor four-game stretch to start the 1974 season, the Indians foolishly included Tidrow in the deal that sent Chris Chambliss to the Yankees for an array of can-miss prospects and pitchers. It was another in a series of brilliant moves by Yankee general manager Gabe Paul, who knew the Indians’ talent base as well as anyone, having worked for the Tribe prior to his relocation to New York.

Yankee manager Bill Virdon called on Tidrow 33 times that season—25 games as a starter and eight as a reliever. The following year, Tidrow worked solely in relief, pitching primarily as Sparky Lyle’s main set-up man, at first for Virdon and then for Billy Martin. Except for two spot starts, Tidrow remained in that role exclusively through the end of 1976. During that time, he built up the trust of Martin, who loved Tidrow’s durability and willingness to take the ball. So in 1977, Martin tested Tidrow by starting him seven times, giving him the ball 42 times out of the pen, and allowing him to finish 26 of those games. In his seven starts, Tidrow compiled a spotless record of 5-0. On the season, Tidrow won 11 games, saved five others, and logged 151 innings. Who does that in today’s game? No one does, that’s who.

Tidrow’s jack-of-all-trades role continued in 1978, only this time with more emphasis on starting. When injuries to Don Gullett, Jim "Catfish" Hunter, and Andy Messersmith threatened to wreck the rotation, Martin and Bob Lemon turned to Tidrow. Making only six relief appearances that season, Tidrow started 25 games. He actually notched four complete games, borderline remarkable for a part-time reliever. That summer, he soaked up 185 innings that might have otherwise gone to the Ken Clays and Larry McCalls of the world. In a season in which Hunter made only 20 starts, Gullett registered only eight, and Messersmith made a mere five, those innings amounted to lifesavers for managers Martin and Lemon.

Many pitchers tend to become regimented and like to follow their routines to the point of superstition. The more defined their roles, the better they like it. If you ask some pitchers to do something outside of their proverbial boxes, they bristle at the suggestion. Not so with Tidrow. Whatever Virdon, Martin, or Lemon asked him to do, he did. We never heard one shred of complaint—at least not publicly. In the Bronx Zoo atmosphere that engulfed the Yankee world in the late 1970s, those gripes tended to get published, yet nothing came from Tidrow.

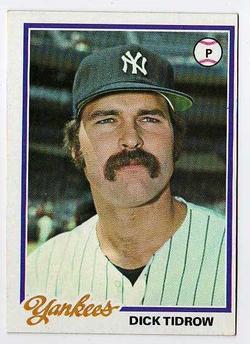

The absence of complaint played a part in the acquisition of his nickname. Teammates called Tidrow "Dirt." He simply did his job, without fanfare or histrionics, like a blue-collar worker who was willing to throw himself into the muck and mire. Old school all the way, Tidrow wore his stirrups high, showing plenty of the Yankees’ navy blue stocking. The rest of his physical appearance also played a large part in the nickname. Tidrow wore his hair longer than most of his Yankee teammates, complemented by an oversized Fu Manchu mustache (seen vividly in his 1978 Topps card above) and the chronic presence of a few days’ worth of bearded stubble. When Tidrow entered a game in relief, it sometimes looked like he had spent a few innings wrestling in a bullpen mud puddle. (Actually, while playing a game called "flip" prior to actual games, Tidrow often dove into the dirt in an effort to keep the ball alive. Hence the dirty uniform.) Somehow Tidrow’s unkempt exterior managed to escape the ire of George Steinbrenner, perhaps because "the Boss" was too concerned about the main carnival participants in his ongoing three-ring circus—Martin, Thurman Munson, and Reggie Jackson.

Tidrow’s look wasn’t his only distinctive feature. His pitching motion left a clear but unusual impression. As part of his windup, Tidrow kicked his left leg high into the air, until he seemingly bounced his knee off his chest, and then released the ball from a three-quarters angle. In many ways, his motion resembled Dennis Eckersley’s, but "the Eck" kept his left leg fully extended while Tidrow flexed his knee.

Tidrow was fun to imitate, but easy to overlook. Frankly, I didn’t really appreciate him until after he left the Yankees. In the midst of a bad start to the 1979 season, Tidrow turned in a lousy performance against the Tigers, raising his ERA to an unspeakable 7.94. After the game, Steinbrenner told vice president and general manager Al Rosen to trade Tidrow—NOW. Making the best possible deal available to him at the time, Rosen sent Tidrow to the Cubs for Ray Burris. While the likeable Burris imploded in pinstripes, Tidrow regained his form, becoming a valuable set-up man, at first for Bruce Sutter and later for Lee Smith.

Sadly, Tidrow has few ties to the Yankees today. He worked for as a special assignment scout with the organization several years before becoming a successful executive with the Giants, where he serves as vice president in charge of player personnel. I have no idea whether he’s particularly good at that job—the Giants have developed young pitching in recent years but virtually no hitting—but it just seems like he should be working for the Yankees in some capacity. If nothing else, he could teach the pitchers a thing or two about being professional, being versatile, and getting just a little bit dirty.

Bruce Markusen writes "Cooperstown Confidential" for MLB.com.