Saturday afternoon’s debacle was the 100th game of the season for the Yankees, and they now sit at 59-41, but that obviously doesn’t tell the whole story of this seesaw season. So let’s take a deeper look by the numbers.

1

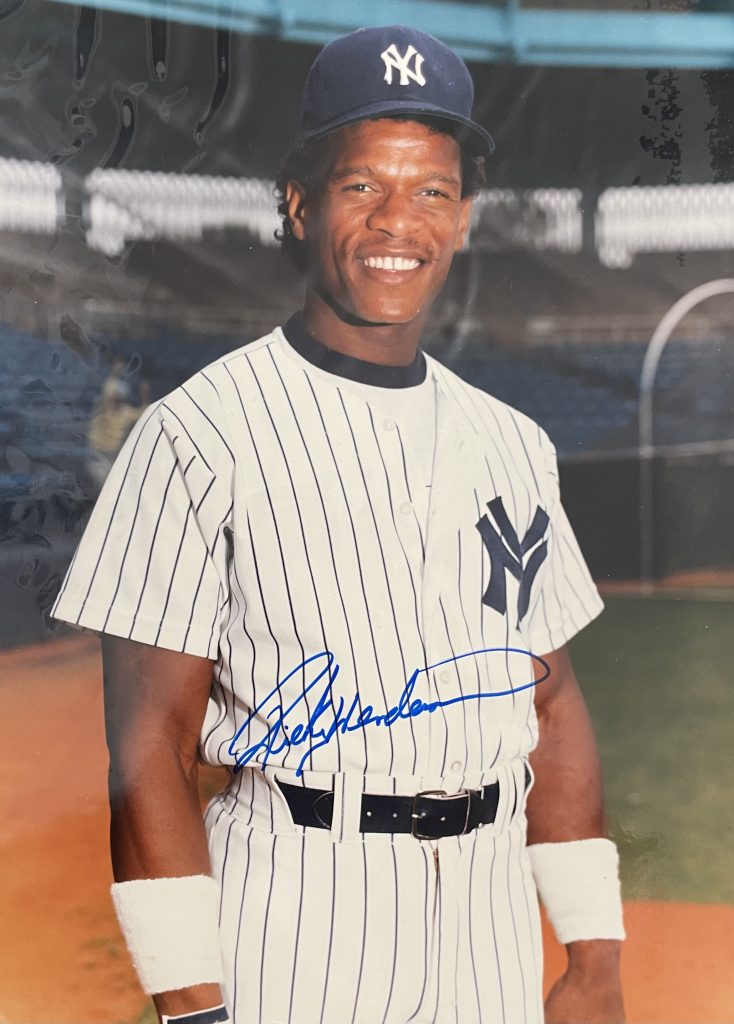

The leadoff spot in the order has been a problem for the Yankees for quite a while now. Brett Gardner held the job for years, DJ LeMahieu was great in 2020 and 2021, but this year has been a struggle, with five different players hitting at the top of the order, Gleyber Torres, Anthony Volpe, Alex Verdugo, LeMahieu, and finally Ben Rice. Anthony Volpe seems to have the tools to do the job for the next ten years, but right now the Yankees are struggling to find someone to hit in the coziest spot in all of baseball.

2

The Yankees are two games behind the Baltimore Orioles in 2nd place in the American League East.

3

We’ve only seen three wins from Gerrit Cole, but in his last two starts he’s thrown 12 innings, allowed 11 hits, 2 walks, and 2 runs while striking out 15 in wins over the Orioles and Rays. He seems like the the Gerrit Cole we remember.

4

Here’s the most perplexing statistic about the team that’s scored more runs than any team in baseball. Juan Soto and Aaron Judge lead the major leagues in on base percentage by a long shot, but the spot behind them has been absolutely anemic. No team’s cleanup hitters have been worse than whichever player Aaron Boone pencils into that slot.

5

The Yankees are averaging (just a touch under) five runs per game — actually 4.95, which is among the best in the game. No team, in fact, has scored more than their 495 total runs.

6

Carlos Rodón’s last six starts have been awful. He’s 0-5 with an ERA of 9.67, and he’s allowed 55 baserunners (including 9 home runs) in just 27 innings. Batters are slashing .336/.410/.656 over that stretch. If I hadn’t watched all this, I wouldn’t believe it.

7

There have been seven different starting pitchers — Nestor Cortes, Carlos Rodón, Marcus Stroman, Luís Gil, Clarke Schmidt, Gerrit Cole, and Cody Poteet.

8

When Oswaldo Cabrera finished a blowout game on the mound, it was the eighth position that he’s played as a Yankee, all positions but cacher and designated hitter.

9

Carlos Rodón has nine wins; Nestor Cortés has nine losses.

10

Ben Rice has ten extra base hits — four doubles and six home runs — and his three home run game earlier this month was one of the highlights of the season.

11

Clarke Schmidt only had 11 starts before an injury sidelined him for a few weeks, but he was good while he was out there. His return, hopefully next month, would be a nice boost for a rotation that’s been struggling.

12

Even though there’s been a lot of concern about the Yankees’ inability to throw out opposing base stealers, they actually rank 12th in opponent steals per game.

13

The Yankees have hit 13 triples, which is sixth in the American League.

14

Aaron Judge has grounded into 14 double plays, most in baseball.

15

Marcus Stroman arrived with the reputation of being a ground ball pitcher, but he’s struggled with the long ball this season, coughing up 15 home runs and headed for what will easily be the highest home run percentage (3.4%) of his career.

16

Trent Grisham has walked 16 times.

17

Marcus Stroman has been good, probably about as good as most were hoping. How could? His ERA+ of 117 tells us that he’s been 17% better than league average, which isn’t bad for a fourth or fifth starter.

18

The Yankees are currently 18 games over .500 — which means they’d finish 90-72 if they go .500 the rest of the way.

19

Luís Gil has been the surprise of the season for the Yankees. He didn’t project to be in the rotation, but he’s made 19 starts, and about fifteen of them have been brilliant. He had three straight bad starts from June 20-July 2, but in his last two starts he’s looked like the world beater that he was in April and May.

20

Carlos Rodón has twenty starts and has given up twenty home runs.

21

Clay Holmes has 21 saves and went to the All-Star Game, but it’s the blown saves that we remember. If the Yankees have plans for October, they’ll need to upgrade the bullpen.

22

Gleyber Torres strikes out 22% of the time (22.4%), which slightly below league average.

23

Gleyber Torres has 23 extra base hits — 15 doubles and 8 home runs. In his first few seasons it looked like Gleyber was on his way to the Hall of Fame, but this appears to be who he is now.

24

Aaron Judge leads the team with 24 doubles.

25

Austin Wells has scored 25 runs. He’s not Mike Piazza, but he’s beginning to look more and more like the catcher of the future.

26

The Yankees have used 26 actual pitchers this season, plus two position players.

27

José Treviño has 27 RBIs.

28

Giancarlo had 28 extra base hits (18 home runs and 10 doubles) before his current injury. His bat has been missed, even if his baserunning hasn’t.

29

Anthony Volpe has walked 29 times.

30

Jahmai Jones has appeared in 30 games.

31

Gerrit Cole has allowed 31 hits.

32

Giancarlo Stanton has a strikeout rate of exactly 32%, which is the highest on the team.

33

The Yankees have hit 33 sacrifice flies, which is second best in the league.

34

Aaron Judge is the most fearsome hitter on the planet, but his 34 home runs tell only part of the story.

35

Reliever Jake Cousins leads the team with a strikeout rate of 35.2%.

36

The organization continues to build its reputation for finding and fixing relievers. This year’s success story is Luke Weaver. He’s appeared in 36 games and posted a 2.47 ERA.

37

The Yankees have played 37 games against the American League East, compiling a disappointing record of 17-20.

38

The Yankees have stolen only 38 bases this season. Only the San Francisco Giants are worse, with 31.

39

LeMahieu’s OPS+ is 39, which is preposterously low. This means he’s a staggering sixty-one percent below league average. His slash numbers are somehow even uglier. Since he has fifteen walks but just three doubles, he somehow entered Saturday’s game with a lower slugging percentage (.207) than on base percentage (.275), which is hard to do. I’d guess there are at least five players in the Yankee system right now who could play third base and top these numbers. It’s time to stop running him out there.

40

Closer Clay Holmes leads the team with 40 appearances.

41

The Yankees have 41 losses this season.

42

Yankee fans were spoiled by Mariano Rivera, and we knew it.

43

Ian Hamilton has a ground ball rate of 43%. (Well, actually 43.8%, but we aren’t rounding.)

44

DJ LeMahieu has a wRC+ of 44, which is 56% lower than league average. This is the worst on the team.

45

Forty-five different players have appeared in pinstripes this season.

46

The Yankees have played 46 games at home, compiling a 26-20 record.

47

Oswaldo Cabrera has struck out 47 times.

48

Number 48 on the roster, Anthony Rizzo, was a drag on the lineup when he was healthy. Ben Rice isn’t exactly Don Mattingly, but I don’t think he’s Kevin Maas, either. It would be disappointing to see Rizzo back in the lineup this season.

49

On June 12 the Yankees finished the day at 49-21. They’ve won ten games in the five weeks since then.

50

Oswaldo Cabrera has made 50 put outs at third base.

51

Oswaldo Cabrera has 51 base hits.

52

Trent Grisham has appeared in 52 games, which is far more than expected. He’s been solid in center field, but hasn’t produced much at the plate. (.188/.292/.376)

53

Oswaldo Cabrera has started 53 games at third base.

54

The Yankees have played 54 games on the road, compiling a 33-21 record.

55

Judge has cooled off recently, but he’s still on pace to hit 55 home runs this season.

56

Gleyber Torres has 56 singles.

57

Aaron Judge has played 57 innings in right field.

58

Luke Weaver has 58 strikeouts.

59

As Aaron Boone is fond of saying, the wins in April and May count just as much as the ones in August and September. He’s not wrong.

60

Sixty percent (60.7) of Aaron Judge’s balls put in play have had an exit velocity of 95MPH or higher.

61

Anthony Rizzo has 61 assists.

62

Yankee pitchers have hit 62 batters, most in baseball.

63

Nestor Cortés has given up 63 earned runs, already the most of any season in his career.

64

Luke Weaver and Michael Tonkin, two of the hardest workers in the bullpen, have combined for 64 appearances.

65

Game 65 was once of the best games of the season. The Yankees and Dodgers were scoreless all night until Teoscar Hernández doubled in two runs in the eleventh. Aaron Judge drove in a run in the bottom half, but the Dodgers held on for a 2-1 win.

66

Juan Soto has 66 RBIs, ninth most in baseball.

67

Clarke Schmidt has 67 strikeouts.

68

Aaron Judge has 68 unintentional walks.

69

Jose Treviño has 69 total bases.

70

Juan Soto has struck out 70 times, while walking 80 times. If this trend continues, it would be the fifth straight season with more walks the strikeouts, an impressive feat in this day and age.

71

In Game 71, the Yankees suffered a walkoff loss to the Royals. It seemed like nothing at the time, but it marked the end of a brilliant start and the beginning of a five-week malaise.

72

In Game 72, the Yankees beat the Red Sox 8-1 in Fenway Park. Alex Verdugo went 3 for 5 with a double, a home run, and four RBIs. It was clear in that moment that the Red Sox had made a huge mistake in trading him, as Verdugo was a key part of the best offense in baseball. And then Verdugo completely disappeared.

73

Aaron Judge has played 73 games in the outfield, 4 in left, 63 in center, and 7 in right.

74

Aaron Judge has walked 74 times this season, second best in baseball.

75

The Yankees have spent 75 days in first place.

76

The Yankees have played 76 games against right-handed starters, going 48-28 in those games.

77

Anthony Rizzo’s OPS+ of 77 is by far the lowest since his short rookie season of 2011.

78

Marcus Stroman has 78 strikeouts.

79

Juan Soto has an OPS+ of 179, which means he’s 79 percent better than league average. Aside from the Covid-shortened 2020 season, this is the best season of his career.

80

Juan Soto leads all of baseball with 80 walks.

81

Marcus Stroman has stranded exactly 81% of the baserunners he’s allowed.

82

Anthony Rizzo has a wRC+ of 82 according to Fangraphs, which is much lower than Ben Rice (118) and lower than all but two Yankees with significant at bats (Oswaldo Cabrera, 79, and DJ LeMahieu 44).

83

Tommy Kahnle has faced 83 batters in his 23 appearances.

84

Alex Verdugo has 84 hits. But not many of them have been recently.

85

Alex Verdugo has an OPS+ of 85, and his abysmal stretch over the past five weeks has been a big reason why the Yankees have struggled during that same period. He peaked when he hit a home run on the first pitch he saw upon his return to Fenway Park, and he’s been statistically the worst hitter in baseball since. He’s probably also cost himself tens of millions of dollars.

86

Aaron Judge leads all of baseball with 86 RBIs.

87

Ben Rice has 87 at bats, roughly 87 more than expected.

88

Gerrit Cole has recorded 88 outs.

89

Probably the most significant under-the-radar injury the Yankees have suffered this season was to #89 Jasson Dominguez. Were it not for his oblique injury, he’d likely be DHing in the Bronx right now during Giancarlo Stanton’s absence.

90

Giancarlo Stanton has struck out 90 times.

91

Ian Hamilton has an ERA+ of 91, nine percent below league average.

92

Juan Soto has played 92 games in the outfield, 89 in right and 3 in left.

93

Fangraphs currently projects the Yankees to win 93 games. (Actually 93.6)

94

The Yankees have hit into 94 double plays, the most in baseball.

95

Anthony Volpe has struck out 95 times, more than anyone but Judge. This is obviously a problem.

96

The average exit velocity of the balls put in play by Aaron Judge is 96MPH. (96.2)

97

According to Fangraphs, the Yankees have a 97% chance to make the playoffs. (Actually 97.9%)

98

Game 98 was the worst loss of the season for the Yankees. They had appeared to right the ship and were a pitch away from sweeping the Orioles and moving into first place heading into the all-star break. But Anthony Volpe bobbled a routine ground ball to allow one run, and then Alex Verdugo misplayed a routine fly ball into a two-run, game-winning double. It was a devastating loss in the final game of the first half.

99

No matter what happens, there’s still Aaron Judge, #99.

100

One hundred games down, just 62 (and hopefully a dozen or so more) to go. Let’s go, Yankees!