In his first installment of our series about the box set of the 1977 World Series, Jay Jaffe mentioned how much his father admired Reggie Jackson:

Reggie made a big impression on my father, himself a second-generation Dodger fan who had no truck with the pinstripes. Via him, Reggie gained larger-than-life status in my eyes. When we played catch, occasionally Dad would toss me one that would sting my hand or glance off my glove. If I complained, he’d shout, “Don’t hit ’em so hard, Reggie!” In other words, don’t bellyache, and don’t expect your opponent to cut you any slack.

Longtime readers of Bronx Banter know that not only was Reggie my favorite player as a kid but he was one of the few Yankees my Dad also enjoyed too. Shortly before my father died earlier this year, I wrote a memoir piece about him and Reggie Jackson. I was thinking a lot about the old man two days ago on Father’s Day, and thought now would be a good time to share this story with you.

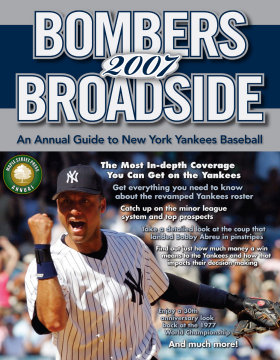

“Dad, Reggie, and Me” was originally published in Bombers Broadside 2007: An Annual Guide to New York Yankees Baseball (March, Maple Street Press). (c) 2007 Maple Street Press LLC. All Rights Reserved.

Dad, Reggie and Me

There is nothing like the first time. Nothing is as intense, as memorable as your first love, your first break-up or, in this case, your first hero. Mine was Reggie Jackson, who signed as a free agent with the Yankees 30 years ago. I was six years old during Jackson’s first year in pinstripes, a time when I was as interested in action heroes and comic books as I was in baseball. Reggie was more a superhero—a “superduperstar” as Time magazine once dubbed him—than a ball player. Bruce Jenner may have been on a box of Wheaties but Reggie had his own candy bar. (Catfish Hunter once said “I unwrapped it and it told me how good it was.”) Reggie arrived in New York at a time when I desperately needed a fantasy hero; his five volatile years in pinstripes coincided with the disintegration of my parents’ marriage.

The truth is the Yankees never wanted Jackson in the first place. In 1976, they won the pennant with an effective left-handed DH in Oscar Gamble. But after they were swept in the World Series by the Reds, Yankees owner George Steinbrenner was bent on adding a big name. The first free agent re-entry draft was held that fall and the Yankees drafted the negotiating rights for nine players. Reggie was their sixth choice. Steinbrenner and his general manager, Gabe Paul, coveted second baseman Bobby Grich; manager Billy Martin pined for outfielder Joe Rudi. Then, over the course of a few days in mid-November, seven of the nine players the Yankees were interested in signed elsewhere, and suddenly Steinbrenner had no choice but to court Reggie. Paul was against it, but Steinbrenner courted Reggie anyway, wining and dining the superstar around New York. In the end, Jackson couldn’t resist the Yankees anymore than Steinbrenner could keep himself from wooing the slugger. He turned down bigger offers from the Expos and the Padres and signed. “I didn’t come to New York to be a star,” he said. “I brought my star with me.”

I remember my father in those years sitting in his leather-bound chair, reading The New York Times, a glass of vodka constantly by his side. In 1976, we moved from Manhattan to Westchester and my father had a heart attack at the age of 39. He was unemployed for a year, horribly depressed. My mother got a job and chopped wood to keep our gratuitously spacious house warm. We moved to a nearby town, Yorktown Heights, in 1977 before my father began to work again.

My dad could be warm and loving. His imitation of the gibberish-talking Swedish chef on The Muppet Show never failed to make my twin sister, younger brother, and me laugh hard from the gut. But he would become furious with us when we didn’t wash our hands for dinner or brush our teeth before bed. My mother’s friend Chrissy, who often substituted for my father on camping trips, whispered to us that he was a bad guy. I remember my parents yelling in their bedroom, my mother smashing plates in the kitchen. (She once painted the floor of my bedroom lime green just to infuriate him.) During the holidays, my father’s eyes would be glassy, and my relatives would glare at him.

Nobody had his back, which made me want to protect him. Like Reggie, my father was an egotist who believed he was somehow being targeted, victimized (Pop led the league in righteous indignation). After Jackson was famously pulled off the field by Martin in a nationally televised game, he told two reporters, “I’m just a black man to them who doesn’t know how to be subservient. I’m a black buck with an IQ of 160, and making $700,000 a year. They’ve never had anyone like me on their team before.” Reggie was the rebel outsider and so was my father. It was Reggie vs. the World, and Dad vs. the World.

Reggie became a fantasy stand-in for my father. They didn’t look alike, but they both wore glasses and had black mustaches and thick torsos. My father’s eyebrows were often raised in anger, and when he yelled, his face turned red and he began to tremble, as if he was going to suddenly pop. When Reggie came to bat, I remember him securing the shiny dark Yankee helmet to his head with his right hand, and then pushing his glasses to the bridge of his nose. Unsmiling, he looked intimidating. Reggie measured his bat out across the plate several times and then stood erect looking out at the pitcher. He’d spit between the space in his front teeth and finally crouch slightly into his stance. Reggie and my old man: they were the two male faces that I was most familiar with.

I was in awe of my father, in the old sense of that word. He had the power to control my feelings. He could make me laugh or cry or convince me that I was lying when I wasn’t. I studied his mannerisms, his gestures, just as I became an expert mimic of Reggie’s practiced, self-conscious movements on the field—the way he wore his uniform, the way he threw the ball, and, most importantly, the way he admired his long home runs.

* * * *

Baseball was the only sport that my dad cared about, though he only followed it casually in The Times. An old Brooklyn Dodger fan, he loathed the Yankees as only someone from his generation could. He thought Billy Martin was a thug and that Steinbrenner was a bully and a boor. But he respected Jackson. Reggie came through in the big spots, and even when he failed, Reggie still evoked wonder. But most of all, Reggie was a true showmen, and my dad loved showmen—from George M. Cohan to Gene Kelly (when he took us to see Superman, he marveled, “It looks like he’s really flying.”) After all, how can anyone deny three home runs on three swings in the sixth game of the World Series?

He admired Reggie’s chutzpah. By the time he came to New York, Reggie was an all-or-nothing player. When he hit a single, I was disappointed; it never filled me up enough. “Reggie would try the impossible,” wrote historian Bill James. “He didn’t mind failing when striving for the spectacular, a trait that all great performers share.”

And like all great performers, Reggie wanted to be needed, loved, worshipped. When he signed with the Yankees, Reggie told reporters, “For me to get applause from the crowd or slaps on the back or have George Steinbrenner say to me that he felt he wanted me to play here and always wanted me here, that’s something I never had. I never felt wanted like that.”

“Reggie doesn’t want just to be recognized,” wrote Sparky Lyle in The Bronx Zoo. “He wants to be idolized.”

I was convinced that Reggie needed me, just like I had to believe that my father needed me. Just like I needed him to come through for me and just like Reggie needed Steinbrenner to like him, and like Martin needed to be the manager of the New York Yankees.

* * * *

Books, not sports, were the proving ground for masculinity in my family. When my paternal grandfather took me to Scribner’s elegant shop on Fifth Avenue to buy a book for me, it was a rite of passage. My grandfather was a circumspect, reserved man who didn’t relate intuitively to small children. My father was convinced that he was born wearing a suit; there was something about him that didn’t wrinkle.

I was allowed to choose whatever book I wanted. My grandfather led me to the children’s section and recommended handsome editions of Treasure Island and Huck Finn. I humored him and then hurried to the sports section and found The Reggie Jackson Scrapbook, a glossy book with a cover photograph of Jackson in his twisted pretzel swing. I didn’t need to look any further. My grandfather shrugged and seemed bemused and then disappointed, but he bought the book for me anyway. I felt guilty, ashamed that I had let him down, but secretly, I was thrilled.

The Reggie Jackson Scrapbook chronicled Jackson’s career from childhood through Arizona State to Oakland, but mostly it covered his first year in pinstripes. Photos were accompanied by bold-faced captions from Reggie himself: “Home run hitters strike out a lot,” and “I’ve got a heck of an arm most of the time.”

Banner headlines from the tabloids and action shots from the playoffs filled the pages—Hal McRae upending Willie Randolph, George Brett fighting with Graig Nettles. One page had a large photo of Reggie superimposed over a series of headlines. An arrow pointed to Jackson’s mouth, and under the picture a caption read, “Sometimes I wish I could keep this thing closed.” On another page was a picture of Reggie lying on the ground near home plate after being hit by a pitch. The caption underneath said, “This is the way I felt almost all year—down. But luckily finding a way to get up and keep going.” Finally, each of his three dramatic home runs in the final game of the ’77 World Series had their own page. The last one showed Jackson watching his longest homer, the one he hit off Charlie Hough. The catcher, Steve Yeager and the home plate umpire had their heads cocked in the air too, like baby birds waiting to be fed by their mother.

Since we read only The New York Times in my house, it was thrilling to see the cartoonish pictures and brash headlines from the Daily News and the New York Post: “Billy + Jax Clash in Dugout,” “Steinbrenner Lectures Club.”

I read and re-read the book. The last two pages featured a shot of Billy Martin drinking champagne in his office after the Series ended. The headline read: “Reggie Lauds Billy: ‘There’s Nobody I’d Rather Play For.'” On the next page was a picture of Reggie at his locker with his arm around his dad, a short, chubby man with a pencil-thin mustache. “Nice guy—that dad of mine!”

* * * *

I was seven when I went to my first Yankee game in 1978, but Reggie was not playing that day and my friend Liz and I were more interested in eating hot dogs, ice cream, and Cracker Jack than in the game itself. It wasn’t until ’79 that I began following the game daily, reading box scores and recaps. Reggie was injured for a good portion of the summer and his fighting with Steinbrenner had begun.

My father’s drinking worsened. My mother kept extra candles in the house that we used when the heating bill went unpaid. Dad seldom played catch with me. It was not fun for him, having to get up from his drink and the Times. He was impatient and irritable, and he threw the ball hard as if he were having a catch with an adult. I recall shedding my glove one day and walking back into the house in tears, wondering what I had done wrong.

I had just turned eight that summer when I visited my mother’s family just outside of Brussels for a few weeks. It was the first time I made the trip by myself and I was palpably homesick. My dad sent me the box score from the All-Star Game and wrote that I had better be speaking French or else. Sitting in the attic room of my grandparents’ home, the smell of tarragon and potatoes drifting up from the kitchen, and the sounds of a British serial on the BBC radio coming from an old tuner in the corner of the room, I cried as I wrote my father a letter. I smudged the tears on the paper, hoping he would notice.

My father cried the day after Thurman Munson died in a plane crash. He sat at his desk with a glass of vodka and watched the ceremony at Yankee Stadium, the smoke of a Pall Mall filling the dim room. He began to sob uncontrollably. I didn’t understand why; he didn’t even like the Yankees. But dad explained to me that sometimes it is sad when a person dies, even if they did play for the Yankees.

* * * *

My dad was given a copy of Sparky Lyle’s vulgar inside-account of the 1978 season, The Bronx Zoo, which I read eagerly, scanning the pages for the word “Reggie.” Along the way, I discovered that a big league locker room was a pungent, vulgar place. I learned many curse words, and how much many of the Yankees despised Reggie. Lyle was loyal to Martin and disliked Reggie’s theatrics. However, he admired Jackson’s ability to produce in key moments, like when he hit a long home run in the playoff game against the Red Sox (which proved to be the deciding run), or when he hit a dinger off the Dodgers’ Bob Welch in the final game of the World Series. “Despite the fact that Reggie at times can be hard to take,” Lyle wrote, “there’s no question that in the big games, he can get way up and hit the hell out of the ball.”

The next year, under new manager Dick Howser, was Reggie’s finest as a Yankee. He hit 41 homers in 1980, which led the league, and batted .300 for the first, and only, time in his career. It was also the final year of my parents’ marriage. That summer, I cajoled and begged anyone I could to take me to see The Empire Strikes Back, the first movie I ever saw more than twice in the theater. Reggie and George and the Dark Side of the Force were all mixed up in my imagination. It was wrenching when Vader told Luke that he was his father, and when the movie ended with a frozen Han Solo being shipped off to the faceless bounty hunter, Jabba the Hut. The movie seemed to be soaked in defeat. My dad was both Han Solo and, as it turned out, Darth Vader. He was both Reggie and George—a bully, the very thing he hated so much in Steinbrenner.

The Yankees won 103 games in the regular season but were swept by the Royals in the playoffs. Howser was sacked, and on New Year’s Eve, my mother decided that she wanted out. She convinced my father to see a therapist with her, which they did for several months. Dad refused to admit that he had a drinking problem and my mother finally had the courage to tell him to leave. By the spring of ’81, we had moved to another Westchester town while dad returned to Manhattan. I desperately wanted to live with the outcast; he was flattered but said that it wouldn’t be practical. Before the summer was over, the baseball players went on strike. Suddenly, everything was so grown up.

It was a depressing year for Reggie as well. Steinbrenner had acquired Dave Winfield the previous winter, and refused to discuss a new deal with Jackson (whose contract was expiring) until after the season. He humiliated Reggie by having his slugger undergo a physical examination while in the midst of a terrible slump. The Yankees made the playoffs again that October and Reggie launched a monumental home run against the Brewers, but he missed the first two games of the World Series due to injury, and was benched in the third game (the order came from Steinbrenner). Otherwise, he played well as the Yankees crumbled in Los Angeles. They finally lost, but it was more than that. I was inconsolable.

As a consolation, my mom bought me a big, gray Venezuelan rabbit. I named him Reggie. He lived in a cage in my bedroom. Though he was house trained, he had an insatiable appetite, eating the corners of my Sports Illustrated magazines and the noses and feet of my sister’s Barbie dolls. He chewed his way through most of our Christmas lights, which killed him a few days later.

* * * *

George Steinbrenner has often said that the biggest mistake he ever made was not re-signing Jackson in 1982. Reggie went to the Angels. I was three-quarters of the way through the fifth grade when he returned to New York for the first time. We still had a 13″ Sony Trinitron, which rested on the dresser of my mom’s bedroom. I sat on the edge of her bed and watched as Reggie hit a long home run off Ron Guidry in the seventh inning. It bounced off the façade of the upper deck in right field and I went wild, running around the house screaming. The landlady downstairs pounded on the ceiling but I didn’t care.

The entire Stadium chanted “Steinbrenner sucks.” I was both happy and vengeful. All the emotions of a difficult first year of divorce spilled out of me when he hit that home run. For the Yankee players, it was a release of sorts too. Guidry placed his glove in front of his face to cover a smile; the players in the dugout loved the chanting. Reggie had escaped the Zoo but reminded everyone that he would be missed. My father wasn’t around, but he would have appreciated the moment. I would see him that weekend in Manhattan, and I was sure to tell him about it.

When he was still living with us, my dad would occasionally come into the den while I was watching the game. Preoccupied with something on his desk (maybe he was looking for a book), he would pause for a moment if he saw that Jackson was batting. These fleeting moments were precious. My father, standing there, a cigarette in his hand, his eyes alight. Dad, Reggie, Me.

Dad would usually make a call: “whiff” or “home run.” He was wrong more often than not. When he called a home run and Reggie struck out, I would be furious, not just disappointed. I thought that my father was purposely denying me. But there were a few times that he called a home run and was right (including once at a game). Although it was Reggie who hit the home runs, I was filled with pride when my dad called them. A surge of power shot through my body. At these moments he was no longer my dad, who drank too much, or belittled me. Instead, he was the man who really mattered in my life. Not exactly my hero like Reggie, but my dad, who, on those rare occasions, righted my world in a way no one else, not even Reggie, could ever do.