"Bill Heinz is a walking contradiction of the stereotype of the phlegmatic Teuton. He is emotional and demonstrative. He can sink into depressions so deep they would give a sandhog the bends. His highs are several stories high. As cityside reporter, war correspondent, sports columnist, freelance journalist, and novelist, he was and is a dedicated craftsman and a penetrating observer who never gives half measure.

‘Bill,’ his doctor once told him, ‘if you don’t stop trying to be the greatest writer in the world, you’re going to kill yourself.’

‘I’m not trying to be the greatest writer in the world,’ Bill said, ‘I’m only trying to be the best writer I can be.’"

Red Smith, from the Introduction to Heinz’s collection, American Mirror.

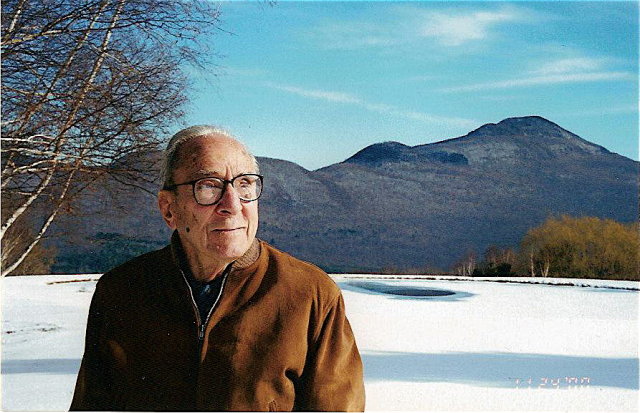

W.C. Heinz, one of the finest journalists this country has ever produced, died earlier this year. A few months ago, a tribute was held in Vermont in his honor, and Adam White wrote a fine piece on the event for the Bennington Banner. In it, he quotes Bob Matteson, who was the editor-in-chief of the Middlebury College newspaper when Heinz was sports editor in 1936-37.

"He could spot make-believe – or phoniness – right away in a person," Matteson said. "And he wanted no part of it."

White continues:

Therein would seem to lie the key to Bill Heinz’s writing, his true method for distilling parable from the mundane. There is a sort of universal admission among those who were close to Heinz that he could be averse to, even dismissive of, certain people and personality types – but there is equally compelling evidence that such an attitude stemmed from his heightened sense of intuition regarding truth. Without such intuition, it is unlikely that he could have even recognized – let alone captured – the majesty and romance that pervades so much of his work.

"The secret is love," (Jeff) MacGregor said. "It’s his empathy, [though] not for individuals; I don’t know that [Heinz] even liked people. His genius was his empathy for the situation that we all share, that common cause of human enterprise. The truth that [Heinz] wrote about is the struggle that we all face, every day, when we get out of bed – and how good a fight we put up before the end of the day."

I find this last paragraph especially gripping. I asked his daughter, Gayl what she made of MacGregor’s observation:

My father had a huge social conscience; he was extremely aware of the condition of society in general, and the debt that Americans, in particular, owe to society. He translated that perception to individuals and had tremendous respect for those who gave of themselves to better the world around them. He had little or no respect for those who made an easy buck (corporate in particular) and spent it on themselves.Did he like people? As a reporter, he had to like people. He spent his career delving into people and practically becoming them in order to effectively portray them on paper. His dismay with people was mostly with those who did not strive to be professionals in whatever their chosen endeavor. "The highways to everyhere," he said, "are crowded with amateurs." And he hated amateurs. And so he didn’t like "people." On the flip side, with his keen sense of humor and insight, he delighted in his observations of people and found great amusement in their idiosyncrasies and personality traits. His greatest amusement? Children. He empathized the most with them.

I think MacGregor’s take on Bill Heinz is right on the money, and I suspect that it could be applied to MacGregor’s work, too. Without empathy, a writer is dead. You’ve got to feel for the people you’re writing about. And I like to think that it helps if you’ve lived and suffered yourself. Think of someone like Breslin at his best. He knew the products of the New York streets he wrote about because he was one of them. He had the same fears and doubts, reveled in the same small triumphs, and probably always suspected that The Man was still going to have his head on a platter by the time his race was run.

When I think of my own work, I realize how easy it was for me to talk to, say, ballplayers who’d spent their careers marooned in tank towns and how little I had in common with team owners, general managers and league executives. It seemed as though I was always at a loss for words when I was around people who had wealth and power. The guys I did best with were the ones who reminded me of the railroad machinist who coached my American Legion team and the old minor-leaguer who taught how to be a catcher. My father may have worn a suit and tie to work — not that we were rich, mind you; we didn’t even come close — but in my heart I was pure blue collar.

Curiosity, empathy, professionalism, authenticity. These are the qualities that count in life, right?