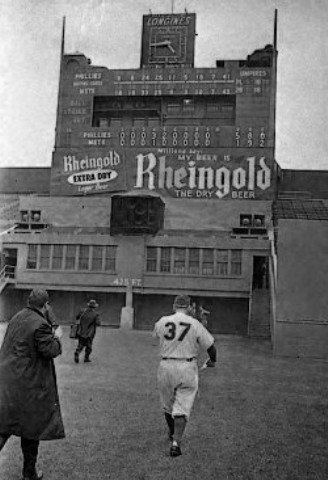

In the coming weeks, we’ll see more than our fair share of tributes to Yankee Stadium. Here are a couple of excellent farewells to the old Polo Grounds…

Arnold Hano, who wrote the terrific account of Game One of the 1954 World Serious, A Day in the Bleachers, was on hand for the Giants last game at the Polo Grounds. He wrote about the experience for Sports Illustrated:

It was a few minutes before one o’clock in the afternoon, and Willie Mays and Valmy Thomas were socializing in center field of the Polo Grounds with Pittsburgh Pirate Outfielder Jim Pendleton, against all the rules of the game. It was obviously going to be that sort of day.

Wafted across the field, through the gravel-throated public-address system, sweet music entertained the early crowd. A fan sang softly, "Sweetheart, if you should stray/A million miles away/I’ll always be in love with you." It was that sort of day.

The sky was gray, and there was a ring around a hazy yellow sun. It was also that sort of day. A fan walked through the bleachers. "Wanna buy a crying towel?" he said. "Buy a set of crying towels." There were no other vendors. You couldn’t buy a scorecard in the bleachers. You couldn’t buy a hot dog or coffee. The vendors hadn’t showed up. The concession stand was open, though. You could get a beer. There are two big signs in the Polo Grounds that read: "Have a Knick." The concession man was selling Ballantine’s.

At 1:32 the public-address announcer said, "Will the guests of the Giants assemble at home plate?" A fan near the third-base boxes snarled, "We’re the guests, you jerks.

Six-and-a-half years later, Roger Angell said goodbye to the Polo Grounds in a short essay for The New Yorker:

What does depress me about the decease of the bony, misshapen old playground is the attendant irrevocable deprivation of habit–the amputation of so many private, and easily renewable small familiarities. The things I liked best about the Polo Grounds were wights and emotions so inconsequential that they will surely slide out of my recollection. A flight of pigeons flashing out of the barn-shadow of the upper stands, wheeling past the right-field foul pole, and disappearing above the inert, heat-heavy flags on the roof. The steepness of the ramp descending from the Speedway toward the upper-stand gates, which pushed your toes into your shoe tips as you approached the park, tasting sweet anticipation and getting out your change to buy a program. The unmistakable, final "Plock!" of a line drive hitting the green wooden barrier above the stands in deep left field. The gentle, rockerlike swing of the tloop of rusty chain you rested your arm upon in a box seat, and the heat of the sun-warmed iron coming through your shirtsleeve under your elbow. At a night game, the moon rising out of the scoreboard like a spongy, day-old orange balllon and when the whitening over the waves of noise and the slow, shifting clouds of floodlit cigarette smoke. All these I mourn, for their loss constitutes the death of still another neighbhorhood–a small landscape of distinctive and reassuring familiarity. Demolition and alteration are a painful city commonplace, but as our surroundings become more undistinguished and indistinguishable, we sense, at last, that we may not possess the scorecards and record books to help us remember who we are and what we have seen and loved.

Man, how I wish I could have seen that joint up close.