Seven Layer Chocolate Cake

By Jane Leavy

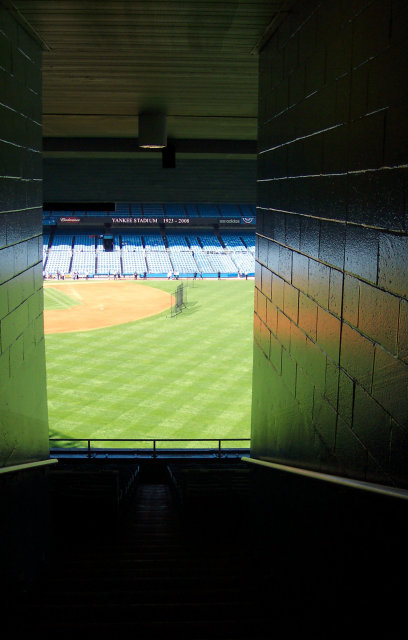

May 18, 1962 was a raw spring night in the Bronx. A mean chill filled Yankee Stadium suppressing attendance at the Friday night game between the Yanks and the Minnesota Twins. A forgotten tributary of the Harlem River, on whose banks the stadium was built, runs on a diagonal from left field toward the hole between third and short—like a cut off throw. The ancient waterway, Cromwell’s Creek, buried deep beneath the sedimentary rock of urbanization, asserted itself in the dew and chill of that otherwise fine Friday evening. Mist enveloped the scalloped copper frieze that ringed the upper deck of the Stadium. I remember thinking: if Mick hits one tonight nobody will ever see it again.

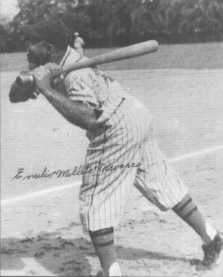

That was the thing about Mantle: you never knew what might happen when he stepped to the plate or what might happen to him.

My father, who grew up on the other side of the Harlem River cheering for the Giants from a rocky perch on Coogan’s Bluff, had gotten box seats behind the dugout along the third base line. It was the best seat I would ever have in a ballpark until I went to work as a sportswriter fifteen years later.

I was ten years old that sweet evening. What could be better-a visit to see The Mick and a sleepover at my grandmother’s? Her apartment was just up the street in a building called The Yankee Arms, a long, loud foul ball from home plate.

Mickey was my guy but I was grandma’s girl, her favorite, I thought (as did all her grandchildren). I knew this because although she loved frilly things and rose sachet, because canasta not baseball was her game, because in the 20 years she lived in the shadow of the ballpark she was never once tempted to step inside, despite all this she put on her mink stole and open-toed shoes and took me to Saks Fifth Avenue to buy my first baseball glove. It was an odd place to go in search of a mitt but she only wanted the best for me.

Providence intervened–a mannequin in the front window had a Sammy Esposito glove on her hand. “We’ll have that one,” my grandmother told the flummoxed salesman, who pointed out it was not for sale. He was no match for a Jewish grandmother, mine anyway. I took Sammy home; I took Sammy everywhere, including the stadium on May 18, 1962.

My grandfather, a manic-depressive immigrant tailor, had made me two identical wool, plaid skirts, one in tones of beige, brown and gold, the other in red and green, Christmas-tree green, perfect for Hanukah. They were reversible and indestructible. A whole wardrobe, these skirts. They went with everything and nothing. He was in a manic mode when he sewed them; their oscillating hems reflected his ups and downs.

In an act of filial devotion (and parental betrayal), my mother had made it a condition of attendance that I wear one of these atrocities. I chose the more muted tones and an overly generous straw-colored Irish cable knit sweater over a white turtleneck. I looked like a pre-pubescent haystack.

In an act of solidarity for which I remain grateful five years after his death, my father went to the concession stand and bought me an adult-size Yankee cap, large enough to hide most of my embarrassment.

I knew it was going to be Mick’s year. It had to be after the disappointment of 1961. God owed him after allowing Roger Maris to claim Babe Ruth’s title as home run king. Being second fiddle made him more loveable to the masses, but not to me–I couldn’t love him anymore than I did already.

“In 1961 I became an American hero because he beat me,” he would say later. “He was an ass and I was a nice guy. He beat Babe Ruth and he beat me so they hated him. Everywhere we’d go I got a standing ovation. All I had to do was walk out of the dugout.”