The Man with Oscar Peterson and Coleman Hawkins:

Monthly Archives: December 2011

The Emmis, Now and Forever

When he was twelve-years-old, Scott Raab saw the Cleveland Browns win the championship game. He was there, in person. No Cleveland team has won a title since, and Raab’s new book, “The Whore of Akron: One Man’s Search for the Soul of Lebron James,” is partly about being a Jew and a Clevelander and it is about noble suffering.

This is a good bit:

I know: it’s only a game. But what a game. The Colts were 7-point favorites, on the road. Coached by thirty-four-year-old Don Shula–drafted by the Browns after going to college in Cleveland–they boasted the league’s best offense, with six future Hall of Famers, led by Johnny U at quarterback–and the NFL’s best defense. But Unitas threw two picks into the wind. Dr. Ryan tossed three TDs, and Jim Brown gained 114 yards. The Browns won, 27-0.

The official attendance that day was 79, 544, and not one of them would’ve believed that he’d never live to see another Cleveland team win a championship.

The Cuyahoga River catching fire?

Maybe.

Fish by the thousands washing up dead on Lake Erie’s shore?

Possible.

Cleveland a national joke?

Not bloody likely.

But the notion that generation after generation of Cleveland fans could be born and grown old and die without celebrating a title?

Get the fuck outta here.

I was there. I saw it happen. It gave me an abiding sense of faith–in my town and its teams–that will never fade, that no amount of hurt and heartbreak can destroy. All those fucking Yankees fans are absolutely right. Flags fly forever. Forever.

“The Whore of Akron” can be purchased here.

[Photo Credit: baseballoogie]

Blahzay Blah in Big D (Bottom’s Up)

The Winter Meetings. Rumors and more rumors. Tweets, texts, posts, and TV updates. Back-slapping, guffaws, plenty of cologne, and more than the occasional malocchio. Oh, and maybe a drink or three. Grown ass men acting like children, only with millions of dollars at stake.

No better place to follow the action than Hardball Talk.

Let the mishegoss begin.

Update: First bit of business has Jose Reyes bringing his talents to South Beach.

Sundazed Soul

Winter Meetings, baby. Tomorrow, the breathless gossip begins. Today, we strut:

[Photo Credit: Sergiu Cioban]

Take the Train, Take the Train

Over at the New York Review of Books, here’s Bruce Davidson on taking pictures on the Iron Horse in the early ’80s:

In the spring of 1980, I began to photograph the New York subway system. Before beginning this project, I was devoting most of my time to commissioned assignments and to writing and producing a feature film based on Isaac Bashevis Singer’s novel, Enemies, A Love Story. When the final option expired on the film, I felt the need to return to my still photography—to my roots.

I began to photograph the traffic islands that line Broadway. These oases of grass, trees, and earth surrounded by heavy city traffic have always interested me. I found myself photographing the lonely widows, vagrant winos, and solemn old men who line the benches on these concrete islands of Manhattan’s Upper West Side.

I traveled to other parts of the city, from Coney Island to the Bronx Zoo. I revisited the Lower East Side cafeteria where I’d photographed several years before. The cafeteria was a haven for the elderly Jewish people surviving the decaying nearby neighborhoods. I photographed the people I had known there, survivors from the war and the death camps who had clung together after the Holocaust to re-root themselves in this strange land. I walked along Essex Street to visit an old scribe who repaired faded Hebrew characters on sacred Torah scrolls. He and his wife, both survivors of Dachau, worked together in their small religious bookstore. Occasionally, he’d allow me to take a photograph as he bent over the parchment with his pen. When the flash went off, he would wave me away. I would return later with prints that he put into a drawer, carefully, without looking at them. Sometimes, returning from his shop during the evening rush hour, I would see the packed cars of the subway as cattle cars, filled with people, each face staring or withdrawn with the fear of its unknown destiny.

Dig the book, a cherce holiday gift.

Oh, hell, and while we’re at it:

The Straw that Stirs the Hub

Guest Post

By Alex Salta (aka Raging Tartabull)

In the years since 2003 it’s become a popular myth that the Yankees/Red Sox rivalry has always been and will always be some kind of Baseball Forever War. Fans of both teams know better–“The Rivalry” has always had its peaks and valleys, and ever since Manny Ramirez of took his talents to Chavez Ravine we’ve been in a punchless valley .

This rivalry needed a jolt to the system and just got one in the form of one of the most volatile managers this side of Billy Martin. Bobby Valentine was only 35 when he started to make his bones as a major league manager in Texas, guiding bad Rangers teams to decent records in a division dominated by the Bash Brothers A’s. Then, after a brief stopover in Japan, he took good but flawed Mets teams to the playoffs back-to-back years losing in the NLCS and one of the best damn 5 game World Series you’ll likely see.

Valentine always had a little Billy in him. The undeniable tactical acumen, the chip on the shoulder, the paranoia that “they” would take it all away from him if given the chance, the charm and the spite. Anytime you steer a team where Jay Payton and Benny Agbayani are daily outfield fixtures to a pennant, it goes a long way to proving you are more than capable as a manager. Conversely, his years-long public feud with former GM Steve Phillips showed that both men knew how to hold a grudge with the best of them.

He could manage his ass off, and he would make sure you knew about it too. This is a man who once referred to the Mets managerial job as “the highest place in any job in the country, in the world, the thing that I live and breathe and die for every second of my life.” Comments like that either suggest tremendous commitment to the New York Mets, or tremendous commitment to promoting the brand of Bobby Valentine, Inc. What side do you think Fred Wilpon felt it landed on? A month after saying it, Valentine was on his way out the door at Shea.

Like Martin, Valentine knew what it was like to climb to the top of the heap in New York and still feel like you weren’t getting enough credit for it. Billy had Reggie and George, Bobby had Steve Phillips and Saint Joe.

Valentine managed the Mets from 1996 through 2002, the exact timeframe when Joe Torre convinced the town that could turn Bigelow Green Tea into wine; Valentine could never hope to be anything more than second banana, content with whatever scraps of media adoration were left over after the latest Yankee victory.

And Valentine was not one to be content with scraps. Mets fans could tell you that; hell everyone from Phillips to George W. Bush can co-sign that one.

Eventually, it all fell apart in a cloud of bizarre press conferences and whatever Tony Tarasco and Mark Corey had in that limo. The Bobby Act had grown tired in Flushing, someone needed Art Howe to come along and light up a room for a change. Bobby eventually packed his bags for the Far East and joined Buck Showalter in the “Managers Everyone Loves When They Aren’t Actually Managing” Club.

Meanwhile, the Red Sox spent the next decade turning themselves into a latter-day version of that Yankee team with tough pitching, long at-bats, and a manager that columnists loved to compare to some kind of mix between John McGraw and Jonas Salk.

Yankees vs. Red Sox became the dominant baseball storyline of the mid-aughts. It got ratings, it sold papers, kept the chatrooms and blogs humming. Still, the rivalry couldn’t sustain the fevered pitch indefinitely. The games between the two teams got longer and longer, the intensity unmistakably lower, and the atmosphere became almost dull.

Then came September 2011 and the grand collapse in Boston, blown saves and extra crispy thighs for all. The Sox got tired of Francona’s “Keep Calm and Win Ninety” style, Prince Theo left town and took his glow with him. The Red Sox needed someone new to come along and light up the room. They–and that “they” is Larry Lucchino–decided Valentine was their man.

Well now he’s back center stage, in a town where he isn’t going to have any trouble finding attention. He’ll manage against the Yankees 18 times next year, and the Joe in the other dugout may be hugely successful in his own right but no one is nominating him for sainthood either. No, it will probably be Bobby who is center stage for those 18 games. Don’t believe it? Just ask him.

Alex Salta is a New York-based writer, he can be reached at alex.salta@gmail.com.

For more on Bobby V:

Observations From Cooperstown: Golden Era Fab Four

On Monday, the Hall of Fame could grow by as many as four. That’s the maximum number of candidates who could be elected by the Golden Era Committee. After giving careful consideration to the ballot, I’ve decided to pass on former players Ken Boyer, Tony Oliva, ex-Yankees Allie Reynolds, Luis Tiant, and Jim Kaat (a particularly tough choice), and longtime executive Buzzie Bavasi.

On Monday, the Hall of Fame could grow by as many as four. That’s the maximum number of candidates who could be elected by the Golden Era Committee. After giving careful consideration to the ballot, I’ve decided to pass on former players Ken Boyer, Tony Oliva, ex-Yankees Allie Reynolds, Luis Tiant, and Jim Kaat (a particularly tough choice), and longtime executive Buzzie Bavasi.

That leaves exactly four men who are deserving of making the grade in Cooperstown.

Ron Santo:

Of the ten men being considered by the Golden Era committee, there is no stronger candidate for election than the late Ron Santo. Arguably one of the five greatest third basemen of all time, and conservatively one of the ten greatest to play the position, Santo has long deserved enshrinement in Cooperstown.

Let’s consider just a few of Santo’s accomplishments. A patient hitter with a keen eye at the plate throughout his career, Santo compiled a lifetime .366 on-base percentage. With 342 home runs, he managed a .464 slugging percentage, despite playing a good portion of his career during an era in which pitchers held major advantages over hitters. Santo’s defensive accomplishments were only slightly less impressive. A five-time Gold Glove winner, the defensively superior Santo led the National League in total chances nine times and led the league in assists seven times. Those numbers indicate that Santo had good range, in addition to the soft hands and ability to start double plays that characterized his long tenure with the Cubs.

With 66 WAR, Santo compares favorably to Brooks (69) and comes within striking distance of George Brett (85) and former Yankee Wade Boggs (89), two offensive-minded third basemen.

Gil Hodges:

Based solely on his accomplishments as a player, or only on his managerial tenure, Hodges likely does not have the requisite resume for the Hall of Fame. But that’s not how the Hall of Fame election process is supposed to work. According to the rules for election, voters are encouraged to consider a candidate’s entire career in assessing his worth for the Hall of Fame.

As a player, Hodges was a fine all-round performer who hit with power, drew walks, and played a Gold Glove-caliber first base, as he contributed prominently to five National League championships for Brooklyn. During his peak, he slugged .500 or better over a span of eight consecutive seasons. As a manager, Hodges oversaw one of the great franchise turnarounds in major league history. He took command of a perennially poor Mets team that had won 57 games, immediately elevated them to a 73-win level, and then engineered one of the most memorable upsets in World Series history. Hodges also maintained the Mets at a level of better than .500 in 1970 and 1971, despite the team’s glaring lack of offense at a number of positions.

In looking at Hodges properly as a combination candidate, the argument for his Hall of Fame election becomes much clearer.

Minnie Minoso:

Like Hodges, Minoso requires more than a surface look to understand his worthiness for the Hall of Fame. He did not become a fulltime major leaguer until the age of 25, through no fault of his own, but because of the Jim Crow segregation that kept black players in the Negro Leagues or the Caribbean.

Over four Negro Leagues seasons, Minoso earned two All-Star game berths and led his teams to two appearances in the Colored World Series. If the game had already been integrated, Minoso might have spent those four seasons playing in the major leagues during his age 20 to 23 seasons.

Even without major league credit for his Negro Leagues years, Minoso’s numbers are impressive. A player in the mold of Enos Slaughter and Pete Rose, Minoso compiled a lifetime on-base percentage of .389 while providing value as both a left fielder and third baseman. Minoso led the league in hits and total bases one time each, in stolen bases and triples three times apiece, and in hit-by-pitches ten times. One of the game’s premier tablesetters, Minoso scored 100-plus runs five times, while topping 90 runs on five other occasions.

Charlie Finley:

Charlie O’s bitter and tempestuous personality will keep him out of the Hall, but an objective look at his accomplishments reveals a deserving Cooperstown candidate. Under the leadership of Finley, the A’s accomplished more during the 1970s than any other major league team, winning three world championships and five division titles. As the team’s owner beginning in 1962, Charlie Finley realized that he was a relative novice at baseball. He listened intently to his scouts—people like Joe Bowman, Dan Carnevale, Tom Giordano, Clyde Kluttz, and Don Pries—who told him which amateur players to pursue as free agents and which ones to draft. As a result, the A’s developed future standouts like Sal Bando, Vida Blue, Bert Campaneris, Rollie Fingers, Catfish Hunter, Reggie Jackson, Blue Moon Odom, and Gene Tenace.

In later years, a more confident and penurious Finley pushed out many of his veteran scouts and tended to ignore the advice of those he still employed. Yet, he still managed to exhibit a deft hand in making trades and signing bargain basement role players. In 1971, Finley made perhaps his best trade, sending an underachieving Rick Monday to the Cubs for Ken Holtzman, who would win 77 games over four seasons in Oakland. Finley also engineered the five-player deal that brought a young left-handed power hitter (Mike Epstein) and an important left-handed reliever (Darold Knowles) to the Bay Area. In 1973, the A’s might not have won the World Series without Knowles, who pitched in all seven games against the Mets.

After the 1972 season, Finley acquired a much-needed center fielder in Billy North for aging middle reliever Bob Locker. In his first four years with the A’s, North played a solid center field, stole 212 bases, and become both a capable leadoff man and No. 2 hitter. Finley also swung unheralded deals for key role players like Matty Alou, Deron Johnson, and Horacio Pina, who would fill important holes in the outfield, at designated hitter, and in middle relief, respectively, during the 1972 and ’73 seasons.

Then there is Finley’s impact as an innovator. He championed the cause for night World Series games, the use of the designated hitter, and interleague play, all before they were officially adopted. He also dressed the A’s in colorful green and gold uniforms, giving the team a unique brand and setting a trend for the game’s changing on-field appearance in the 1970s.

Bruce Markusen writes “Cooperstown Confidential” for The Hardball Times.

Back in the Swing of Things?

Over at River Ave Blues, Joe Pawlikowski suggests that Mark Teixeira could be 2012’s biggest offensive addition for the Bombers.

Oh, and check out this interesting note by Chad Jennings on the lack of trades made by the Yankees in the last year.

One Last Whiskey Dawn

No Regrets: A Hard-Boiled Life

By John Schulian

The train to glory left without James Crumley, who seems to have been too busy examining life’s gnarly side to bother catching it. There are no best-sellers for him, no money-bloated deals with Hollywood–just hard-boiled novels that are better than anybody else’s because all those lost nights stashed in the margins make each one a survivor’s story.

Crumley has never shot a man in Reno just to watch him die, but he knows how blood looks when it’s spilled against a backdrop of whiskey dawns, cocaine pick-me-ups, and wall-shaking sex. His is a wisdom acquired by bellying up to the bar in roadhouses where bikers, ranch hands and oil-field workers beat each other senseless for playing the wrong Merle Haggard song on the jukebox. It’s no life for the delicate, but the delicate don’t have a taste for Crumley’s novels anyway, so the hell with them.

The time is right for saying so now that Crumley has again unleashed Milo Milodragovitch, one of his two memorably unapologetic rogue heroes. Milo comes barreling back in “The Final Country” because he needs something to keep Texas and a woman who’s the queen of mood swings from driving him crazy. To tell the truth, he’d rather be home in Montana after reclaiming his father’s stolen inheritance and snagging some unlaundered drug money in the process. Failing that, he uses a sap on a sucker-punching lady bartender, knocks the teeth out of a one-armed man’s mouth, and almost twists the nose off a security-company executive’s face–all before the shooting gets serious. Crumley, for what it’s worth, says Milo represents his kinder, gentler side.

They’ve both passed 60 without a whimper, no problem for Crumley, but strange territory for a hero in a genre that avoids aging as if it were a homely blond. Be advised, though, that when readers first met Milo, in “The Wrong Case,” in 1976, he was in strange territory for a PI then, too–the modern West–and he survived nicely. So when he talks about the two white streaks in his hair early on in “The Final Country,” he isn’t worried. It’s like he says: “I’m old, babe, but not dead.”

Of course, he comes close to making a liar of himself when the simple job of tracking down a runaway wife puts him in the path of a drug dealer “no larger than a church or any more incongruous than a nun with a beard.” The drug dealer, fresh out of prison, is looking for a woman, too, and when he doesn’t succeed, he decides the next best thing is to kill a bar manager. In the midst of the mayhem, over drinks, naturally, he and Milo connect. So it is that Milo decides to help a guy who doesn’t look like he needs any.

The set-up is straight out of Raymond Chandler’s “Farewell, My Lovely,” which Crumley admits and which, when you think about it, is only fitting since he has been described as Chandler’s “bastard son.” Anyone who doubts the accuracy of that label should read Crumley’s 1978 masterpiece, “The Last Good Kiss.” With all due respect to Elmore Leonard, James Lee Burke and the genre’s other heavyweights, it’s the best hard-boiled novel of the past 25 years. Some admirers swear it is even more than that, comparing it to Jack Kerouac’s “On the Road” and Hunter Thompson’s “Fear and Loathing in Las Vegas.” To make their case for Crumley’s artistry, true believers don’t have to go any farther than “The Last Good Kiss’s” first sentence:

“When I finally caught up with Abraham Trahearne, he was drinking beer with an alcoholic bulldog named Fireball Roberts in a ramshackle joint outside of Sonoma, California, drinking the heart right out of a fine spring afternoon.”

The hero of “Kiss” is C.W. (Sonny) Sughrue, whose last name, as Crumley once explained it to me, is pronounced “sug as in sugar and rue as in rue the goddamned day.” Sughrue is a little younger than Milo and he isn’t as bright, but he’s a lot meaner, which comes in handy for a private eye wading through obsessions, sordid pasts and the dark places in men’s souls. When questioning a particularly difficult thug, Sughrue shoots him twice in the foot: “‘Once to get his attention…and once to let him know I was serious.’”

Culture critic Greil Marcus recalled that quote in the issue of Rolling Stone devoted to the September 11 attacks, as if to suggest that America can play as rough as any terrorists. But the quote’s presence so many years after it appeared in a novel that didn’t sell all that well also suggests an enduring fascination with Crumley. It’s not just that there’s enough demand for his six novels before “The Final Country” to keep reviving them as paperbacks; it’s that there are people who pay upwards of $300 for leather-bound copies of scripts he has written for movies that were never made. And there are even more people, it seems, who will gladly recall finding this expatriate Texan in his Missoula, Montana, lair and joining him in debauches worthy of rock stars.

Documentation of such events is hard to come by, if not impossible, but nothing Crumley has written or said in interviews discourages the telling of such tales. “I think there are more people who drink a lot in America than ever show up in fiction,” he said once, the implication being that he was one of them. And he said, and implied, the same about drugs. But there was a 10-year lull after 1983’s “Dancing Bear” that left the impression his excesses may have gotten the best of him. When he finally reappeared with “The Mexican Tree Duck,” he used the acknowledgments to thank his agent for sticking with him and his publisher for gambling on him. The sentiment didn’t sound like it was coming from someone who’d been lounging on top of the world.

Three years after that, Crumley delivered “Bordersnakes,” which teamed Milo and Sughrue for the first time. And now there is “The Final Country,” his finest work since “The Last Good Kiss,” a splendid balancing act between Milo’s sense of moral outrage and his flare for the outrageous. It’s good to know there’s still a private eye who can enjoy a ménage a trois and then face down a rich, corrupt Texan he sees as “a hyena in the rotten wake of the multinational prides.”

Crumley obviously has a full head of steam, and the news from his camp is that he’s deep into writing his next Sughrue novel, “The Right Madness.” It’s hard to say what’s driving him. Maybe he feels the dogs of mortality nipping at his heels, maybe he has decided to get the most out of his vast talent. Not that he has ever given the impression of someone burdened by regrets. He did, however, apologize the day he showed up 10 minutes late for a writers’ panel on which he was the cult hero.

“I lost my watch,” he said.

“Any idea where?” asked an unsuspecting straight man.

“Yeah,” Crumley said. “I threw it out a car window in El Paso in 1978.”

Crumley died in 2008 at the age of 68. This piece originally appeared on MSN.com (12/3/2001).

Taster’s Cherce

My wife is a Ho for pecan pie. Seriously, it’s embarrassing. She likes to pick off the nuts and just eat the filling. I can’t take her anywhere, I tell you.

I don’t have any strong feelings about pecan pie but for the sake of either inspiring or grossing out the Banter’s resident food-tasters, Thelarmis and Chyll Will, check out this tasty recipe for chocolate pecan pie from David Lebovitz.

The Stacks

Check out these blog posts about how people organize their books. I’ve arranged my books by topic but am too lazy to do it by author within a topic. Sometimes, I do it by size, or I clump together one author’s titles.

Once a year, I might be inspired to clean the mess up but maintaining it is another thing. Plus, I’m forever running out of space so things tend loose any sense of strict purpose. What I need is more space (the New Yorker’s lament), or less books, or a nook or a kindle. But I can’t imagine not collecting more books. It’s how I was raised and I don’t see it stopping.

Course, there’s also the books that are stacked on my night table, but here’s a look some of my library.

Beauty and the Beast

Tonight at the Varsity Letters speaking series, Harvey Araton will talk about his new book about the great Knicks teams from the 1970s, and Scott Raab will discuss his latest, “The Whore of Akron: One Man’s Search for the Soul of Lebron James.” They will be joined by True Hoop blogger, Henry Abbott.

Promises to be a fun evening.

Color By Numbers: A King And A Prince

So far, the Hot Stove has resembled more of a cold shoulder. Despite some very high profile names, the early transactions this offseason have mostly involved a myriad of middle infielders and back-up catchers. Although the wheeling and dealing should ratchet up a notch during next week’s Winter Meeting, the relative silence to this point has been a little surprising.

Among all the free agents available on the market, Albert Pujols is the cream of the crop. However, with the exception of a recent report about interest from the Cubs, there hasn’t been much talk about where the three-time MVP will wind up. In fact, there was more early speculation surrounding Pujols last year, when he and the Cardinals flirted with a contract extension.

There are two factors complicating Pujols first crack at free agency. The first one is the major market teams either already have a big ticket first baseman (Yankees and Red Sox) or are currently embroiled in a financial morass (Dodgers and Mets). The second factor is the free agency of fellow first baseman Prince Fielder, who is not only four years the junior of Pujols, but, in 2011, actually had a better season with the bat than the Cardinals’ stalwart.

Top-10 Career OPS+ Leaders

Note: Minimum 3,000 plate appearance

Source: Baseball-reference.com

Despite some of the concerns about Pujols emerging mortality, it’s worth noting that while his OPS+ of 150 was the lowest of his career, that level of production was still eighth best in the National League (and higher than Fielder’s career rate of 143). That some would consider his 2011 campaign worthy of a red flag indicates how historically spectacular Pujols’ career has been.

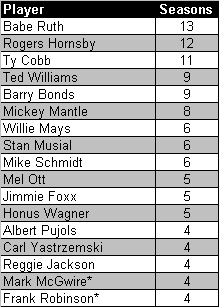

Most Seasons as OPS+ League Leader

*Was the leader in both the American and National Leagues.

Source: Baseball-reference.com

Only seven players with at least 3,000 major league plate appearances can boast an OPS+ higher than Albert Pujols’ career rate of 170, and all of the names ahead of him qualify for the inner circle of baseball’s immortals. On a per season basis, Pujols has led his league in OPS+ on four different occasions (including three straight seasons from 2008 to 2010), an accomplishment bettered by only 12 other players.

Intuitively, most people have regarded Pujols as the best hitter, if not best player, in the game, at least up until last year. Instead of awarding that title subjectively, however, I thought it might be interesting, and fun, to pass the torch using statistics. For this purpose, OPS+ seemed like the best metric to use. Although there are other statistics like wOBA that better measure overall offensive performance, OPS+ still has the advantage of being more well known, easier to compute, and adjusted for ballpark and era. Also, instead of taking one-year snapshots, sustained periods of excellence seemed more appropriate. Is 10 years the right barometer? That can be debated, but if it’s good enough for the Hall of Fame, it’s good enough for me.

“Diamond Kings”: Succession of OPS+ Leaders Over 10-Year Periods

Note: Minimum 5,000 plate appearances for each 10-year period.

Source: Baseball-reference.com

Based on the chart above, Pujols has been a Diamond King for the past four seasons, joining a royal lineage that began with Nap Lajoie and almost exclusively includes undisputable legends. A quick scan of the list reveals all the names you’d expect to be included: Honus Wagner, Ty Cobb, Rogers Hornsby, Babe Ruth, Lou Gehrig, and so on. However, there are some surprises. Bill Nicholson is probably a name not well known even among many diehard fans, but for three 10-year periods, he ranked as the top hitter in the game. Of course, his era of dominance happened to coincide with World War II, which, at the risk of disparaging his accomplishment, probably explains his inclusion. The only other ranking member of the list who isn’t in the Hall of Fame (excluding those not yet eligible) is Dick Allen, who was the top dog for four 10-year periods. Unlike with Nicholson, however, there is no extenuating circumstance. Allen’s career OPS+ of 156 ranks among the 20 best all-time, which makes his Cooperstown snub one of the most unfortunate.

Two other unlikely names who can lay claim to an OPS+ crown also happen to be former Yankees. Although no one would dispute that Wade Boggs and Rickey Henderson were all-time greats, their presence atop a list that disproportionately favors sluggers is somewhat surprising. Nonetheless, it does help to illustrate how complete their offensive games really were. In many ways, Henderson and Boggs are two of the most underrated Hall of Famers, even though most people hold them in very high regard.

Finally, the biggest surprise from the list above is one who is not included: Ted Williams. If the threshold considered had been 4,000 plate appearances, Teddy Ballgame would have been front and center for most of his career. However, because of his two stints as a fighter pilot in the Marine Corps, the Splendid Splinter never qualified. I like to think his exception proves the rule.

Pujols’ status as one of the greatest hitters in baseball history isn’t exactly a secret, but it’s still impressive to consider his body of work within the context of the all-time greats. Entering his age-32 season, the future first ballot Hall of Famer may no longer be in his prime, but if continues to keep the same company he has enjoyed for his entire career, there’s no reason to think his twilight will be a flicker.

Where will Pujols end his career? In St. Louis? How about Chicago? Pinstripes might look nice. Regardless, Prince Albert remains the King, and my bet is he isn’t yet ready to submit to a succession.

--Earl Weaver