Alex Rodriguez stood alone as baseball’s only $200 million man for a decade, but now he has company. In the last six weeks, the fraternity has tripled with the addition of Albert Pujols and Prince Fielder. However, Arod still remains firmly planted atop baseball’s all-time salary totem pole.

10 Highest Paid Players in Baseball History, by Total Value and AAV

Note: Roger Clemens signed a pro-rated $28,000,022 deal with the Yankees in 2007, but he was only paid $17,400.000.

Source: Cots Contracts

If anyone was going to top Arod’s $27.5 million average annual salary, it seemed as if Albert Pujols would be the man. However, the new Angels’ first baseman “settled” on a contract that will pay him $24 million over the next 10 years, meaning he not only fell short of Arod’s current deal, but also failed to topple the contract Rodriguez signed with the Rangers in 2001. As a result, the Yankees’ third baseman seems to be a good bet to remain the highest paid player in baseball history for several more years.

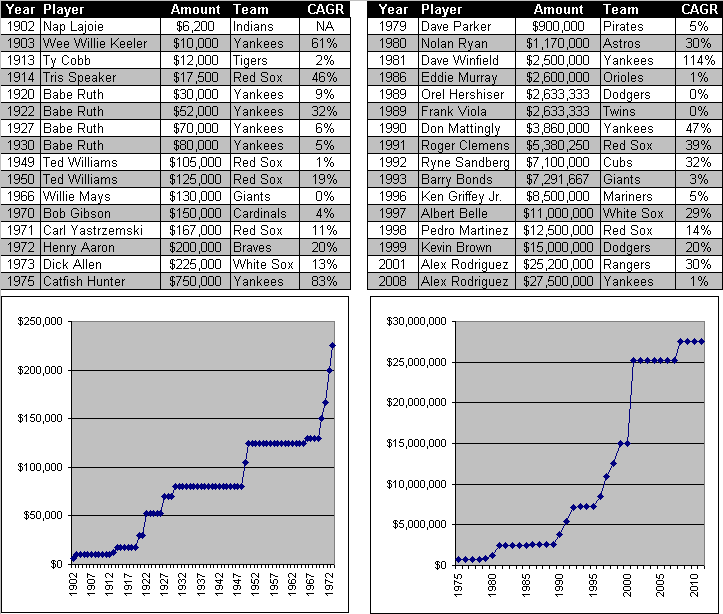

Only two other players have had a longer reign as baseball’s all-time highest paid player. Babe Ruth remained atop the financial heap for 29 years, a period that began when he first joined the Yankees in 1920 and continued until 1949, when Ted Williams finally surpassed the $80,000 earned by the Bambino in 1930 and 1931. After the baton passed from the Babe to the Kid, Williams carried it for another 17 years until Willie Mays finally claimed the throne. Between that point and Arod’s mega-$252 million deal in 2001, the title of highest paid player repeatedly changed hands like a hot potato, with some players claiming the distinction for only days.

Yearly Progression of Baseball’s Highest Paid Player

Note: Records for the period before Babe Ruth are not as complete. Salaries represent average annual contract values with bonuses included. In some cases, actual contract values may have been higher or lower based on interest/inflation adjustments and performance incentives. The highest paid designation was awarded to the player with the top average annual salary before the start of each season.

Source: archival newspaper accounts

Because of Ruth’s immense talent, his salary almost became a defacto ceiling for future players’ demands. In addition, the depression and World War II played a role in keeping players’ ambitions in check, as did the imposition of salary limits by the government’s Wage Stabilization Board during the early-1950s. Although players like Ted Williams and Joe DiMaggio finally surpassed the Babe’s benchmark and broke the $100,000 plateau during this period, it wouldn’t be until the mid-1960s when salaries started rise again.

In 1966, Willie Mays became the highest paid player in baseball history with a salary of $133,000, and then the dominoes started to fall. In the 1970s, a new player became the top man in almost every season, but in 1975, Catfish Hunter put them all to shame. After the 1974 season, Hunter discovered that Athletics’ owner Charley Finley had failed to fund an annuity as stipulated by his contract, so he claimed a breach and was eventually awarded free agency by an arbitrator. Fresh off four consecutive 20-win seasons, Hunter became the subject of a bidding war that was eventually won by George M. Steinbrenner. Hunter’s average contract value of $750,000 (his salary was much lower because of annuity deferments and other consideration) set the stage for the era of free agency that came to a crescendo when Tom Hicks handed out a whopping $252 million contract to Alex Rodriguez 25 years later.

For how much longer will Arod remain baseball’s salary king? This winter, Pujols and Fielder took their best shot at claiming the throne, but came up short. And, with more and more young superstars opting to sign long-term extensions before reaching free agency, it could be awhile before someone surpasses Rodriguez’s average annual salary of $27.5 million (which could wind up being even higher if certain milestone bonuses are achieved). Then again, with baseball enjoying unprecedented economic growth, maybe a $300 million/$30 million man is not that far away?