Check out these beautiful photographs by Andrea Gentl over at the lovely site Hungry Ghost (food+travel).

Monthly Archives: January 2012

Afternoon Art

[Photo Credit: Nina Ai-Artyan]

New York Minute

Dial “W” for murder.

A photo gallery of Weegee’s murder photography over at the most wunnerful How to be a Retronaut.

Here’s another Weegee gallery, this one at the New York Times.

En Garde

Top 10, 20, or Top 100 lists are superficial and dopey. In the right hands, however, they can also be a ton of fun. Especially when the author embraces the silliness of it all, like Bill James does over at Grantland in his list of the 100 best pitchers’ duels of 2011 (“My list of the 100 best pitchers’ duels of 2011 is better than your list, for one reason and one reason only. You don’t have any list.”).

Dig in.

Million Dollar Movie

Here’s a selection of some of Jack’s Greatest Hits, the temper-temper blowups. They are obvious, and perhaps uninspired, highlight reel selections, yet still damned entertaining.

Easy Rider:

Five Easy Pieces:

Carnal Knowledge:

The Last Detail:

Chinatown:

Here’s the ballgame scene in Cuckoo’s Nest.

The Shining:

Terms of Endearment:

Cool and Calm

Coming close to the dead of winter. Not much doing for the Yanks as they wait to finalize the Pineda-Montero trade. Here’s a throwaway piece by Alvaro Morales at ESPN featuring Alex Rodriguez. Over at River Ave Blues, Ben Kabak makes a brief (and flimsy) case for Johnny Damon. And at It’s About the Money, Stupid, Chip Buck has an informative Q&A with Jim Callis of Baseball America.

Otherwise, it’s cool and quiet round here. Snow coming tonight.

Jock Art

Check out this fun gallery of sports posters from the 1980s over at SI.com.

Kenny Easley was my man.

Color By Numbers: The One that Got Away

Whenever a team makes a trade involving a young prospect, there’s always a fear he’ll wind up becoming a superstar. Considering the potential of Jesus Montero, that concern had to be foremost on Brian Cashman’s mind as he agreed to send the young hitter to the Seattle Mariners in exchange for Michael Pineda, a very promising prospect in his own right.

Years ago, before the information age, prospects seemed to magically appear on the doorstep of the major leagues. Nowadays, however, fans have the ability to track a player’s progress from the moment he is drafted until he takes his first pro at bat, so it’s easy to understand why many develop an attachment to homegrown prospects. And yet, in most cases, the pent-up anticipation usually leads to disappointment.

Since 1901, 379 position players (includes actives) have made their major debut in pinstripes, but only 52 ended their careers with a WAR higher than 15. Of that subtotal, all but 13 either spent most of their careers with the Yankees or were traded after establishing themselves in the big leagues, including 20 of the top 21 on the list. So, for the most part, the Yankees have been pretty good at not giving away their best position player prospects.

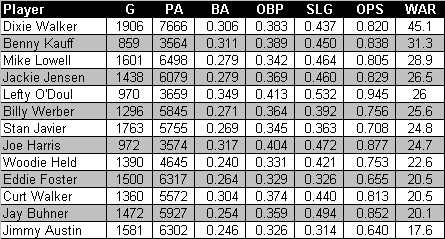

The Ones That Got Away

Note: Includes players with a WAR greater than 15 who were traded by the Yankees early in their careers.

Source: Baseball-reference.com

The only discarded Yankee whose career WAR would rank among the franchise’s best homegrown talents is Dixie Walker. After compiling only 422 plate appearances in five seasons with the Yankees, the 25-year old Walker finally blossomed after being sold to the White Sox for $12,000 in 1936. At the time, the Yankees were a powerhouse team about to embark on a four-year championship run, so there was little room for Walker. However, the move still proved to be short sighted, but not until two other teams also passed him over. Once Walker landed in Brooklyn, his career finally took off. In nine seasons as a Dodger, the outfielder compiled an OPS+ of 128 and received MVP votes in seven years. Admittedly, most of Walker’s success came during the war years, but that makes his loss even more regrettable from the Yankees’ standpoint. Had the team not traded him so many years earlier, perhaps Walker’s presence in the lineup would have helped the Bronx Bombers weather the loss of so many others to military service and avoid what for the Yankees was a long World Series drought from 1944 to 1946.

Mike Lowell’s ranking on the list is perhaps the most relevant in light of recent news because, like Montero, he was traded as part of a prospect swap. At the time, the Yankees had a stacked offensive team and decided to make a new three-year commitment to 3B Scott Brosius, which made Lowell expendable. Unfortunately, Ed Yarnall, the pitcher the Yankees received in return, didn’t exactly pan out. After only 20 innings in the Bronx, the lefty was traded to the Cincinnati Reds before departing forJapan. Needless to say, Cashman is hoping Michael Pineda does a lot better.

Like Lowell, Jackie Jensen is another discarded Yankee who eventually made his bones in Boston. In 1951, Jensen had a very strong campaign in limited duty, which he parlayed into being named Joe DiMaggio’s replacement the following year. Unfortunately for Jenson, that honor was short lived. In fact, it only lasted seven games. After hitting .105 during the first week of 1952, Jensen was traded to the Senators for Irv Noren. In the aftermath of the deal, Casey Stengel admitted that Jensen had talent, but stressed the Yankees’ need for a centerfielder who could “hit, run, field, and throw”. Of course, the irony was the Yankees already had someone on the roster who fit the description. His name was Mickey Mantle.

“We need a centerfielder who can hit, run, field and throw. I tried to give Jensen the job, but he couldn’t hit for me. I couldn’t wait any longer.” – Casey Stengel, quoted by the New York Times, May 4, 1952

Less than a month after the trade was made, Mantle was installed as the new center fielder and Noren was reduced to playing a utility role. Meanwhile, Jensen started to find his swing with the Senators, leading AP to suggest that the Yankees “pulled a whopper” by making a rare bad trade. Despite two solid seasons in Washington, Jensen really made his mark with the Red Sox. In seven seasons with Boston, the outfielder compiled an OPS+ of 123 and punctuated his career with an MVP in 1958.

Although his name appears at the bottom of the list, Jay Buhner probably stand outs to most fans as the best example of the Yankees trading away a promising young hitter. Seinfeld is largely to thank for that, but Buhner’s OPS+ of 125 with the Mariners wasn’t a work of fiction. Adding insult to injury, Buhner also tormented his former team on the field, batting .283/.379/.548 in over 400 regular season plate appearances to go along with a line of .366/.422/.537 in three post season series.

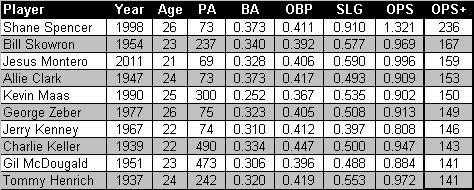

Top-10 OPS+ by Yankees in Their Debut Season

Note: Based on a minimum of 50 plate appearances.

Source: Baseball-reference.com

Albeit in only 69 plate appearances, Jesus Montero had the third highest OPS+ among all position players who debuted with the Yankees. That might seem like a bad omen, but he is surrounded on that list by more than a few players whose careers proved to be disappointments. Will Jesus Montero also follow that path, or join (and perhaps top) the list of young players who excelled after being trading by the Yankees? I wonder what Larry David thinks?

Afternoon Art

“My Daddy’s Gun,” Print by Emory Douglas

Million Dollar Movie

Jack Nicholson is stuck in Cuckoo’s Nest/Shinning mode for most of Bob Rafelson’s turgid 1981 remake of The Postman Always Rings Twice. His character, an ex-con in his mid-forties, was 24 in James M. Cain’s novel. Here, he feels underdeveloped and it’s hard to tell if the guy is sinister, a sap, or a heel. It is as if the actor and director never got a handle on who they wanted the character to be.

What’s compelling about Nicholson’s performance is that he doesn’t chew the scenery. He may fall back on his familiar screen persona but he’s restrained, too. Best of all, he’s generous and lets Jessica Lange dominate the movie.

The sexual charge between Nicholson and Lange is undeniable.

She is tough and it is refreshing to see a woman play a femme fatal and not look like a waif. Early on, she shoots Nicholson a look while she pours wine for her husband that’s enough to stop any man–or woman–dead in their tracks.

You can see why she’d drive a person to do crazy things. The pulp is drained out of this version (written by David Mamet, shot by Sven Nykvist)–it’s not nearly as appealing as the John Garfield original–but the electricity generated by Lange keeps you watching, and her sex scenes with Nicholson are savage and hard to forget.

For more, check out this article by Patrick McGilligan in American Film: The Postman Rings Again

Leave the Gun. Take the Cannoli.

I can’t relate to pitchers. I had to take the ball from the second grade up through freshman year of high school and I hated it most of the time. I could hit, though, until it was too dark out to see the ball. If my dad’s arm didn’t get tired, we might still be out there.

On a basic level, hitting is reaction and pitching is initiation. I’ve always had trouble getting started. I’d rather get a feel for something first and join in progress. And the precision required to throw it exactly where you intend every time? Screw that, let me just hit the ball as hard as I can and we’ll see what happens.

Maybe this prejudice influences the way I envision a baseball roster. The lineup is the body, the pitching staff is the wardrobe. The appearance of the team changes game to game based on the pitcher, but the core is the same. The ace is your best suit, your best reliever could be your smoking jacket. (I guess A.J. Burnett is your kid’s urine-soaked PJs)

So when I heard Jesus Montero was traded for Michael Pineda, I felt like we were trading a neck for a necktie. Sure, the tie is important, but without the neck, what’s the point?

Even without the catching, I’ll take Montero’s simple, solid bat over the complex musculature of Pineda’s throwing arm. You can watch Montero hit every game, all season long. There’s no better way to interface with a team than through a star hitter, especially for a young fan, because he’s always in the lineup.

I understand that having Pineda in the rotation probably makes the 2012 Yankees a better team than they would have been with Montero as the DH. But in 2013? And 2014?

Arod and Teixeira are already fractions of what they once were and they will be declining in the lineup for years to come. The Yankees have one big hitter in his prime, Cano, who is fierce but not flawless. You don’t have to squint too hard to see a Yankee team desperate for hitting.

The more I think about the trade, the more comfortable I am with Cashman’s logic and his vision. But I am firmly on the Montero side of the debate. It boils down to this: if they both become stars, I’d want Montero to be a Yankee.

Beat of the Day

Mid-’90s Gem.

New York Minute

There was a cool photo gallery of Steven Siegel’s photography yesterday at The Gothamist.

Afternoon Art

Picture by Carole Bremaud

Analyze This

There is a long piece by David Kamp on the late Lucian Freud over at Vanity Fair:

Freud’s was not one of those postscript deaths, the final headline in a life that had long ago ceased to matter or progress. It was an interruption—the ultimate inconvenience for a man who still had plenty of work to do and plenty of people who wanted to see his work. The restaurateur Jeremy King, who was more than a hundred sittings into an uncompleted etching when Freud died—having already sat for a painting completed in 2007—recalls that the artist “never came to terms with the fact that he was slowing down. He constantly said, ‘What’s wrong with me?’ And I’d say, ‘Well, Lucian, you’re actually much more active than any other 68-year-old I know, let alone 88.’ And the moment he lifted his hands, most of his ailments seemed to melt away. The concentration and the adrenaline pushed him through.”

From his mid-60s onward, the pinochle years for most men his age, Freud had been enjoying a fruitful and vigorous late period. This wasn’t a function of critical recognition, though it happened to be in this period that critical favor finally smiled upon him, with Time’s Robert Hughes judging him “the best realist painter alive,” a sobriquet that stuck. Nor was it a matter of commercial success, though it was in 2008 that Freud’s Benefits Supervisor Sleeping (1995) fetched the highest-ever auction price for a painting by a living artist, selling at Christie’s to the Russian petrogarch Roman Abramovich for $33.6 million.

Freud simply did great work as an old man, some of his greatest. “In a sense, I think he knew this was his last big push at making some remarkable works. I could just see that he was really ambitious, pushing as hard as he could,” says the naked man in that final painting, David Dawson, the artist’s longtime assistant and the owner of Eli, the whippet star of several late paintings. (Freud had bestowed the dog upon Dawson as a Christmas present in 2000.) When Dawson started working for Freud, 20 years ago, the artist was in the middle of a series of nudes of the drag performer and demimonde fixture Leigh Bowery. Bowery was a huge man, lengthwise and girthwise, with a bald, oblong head—a lot to work with in terms of topography, physiognomy, and epidermal hectarage. Yet Freud went bigger still, painting Bowery larger than life-size. Freud had his canvases extended northward, eastward, and westward as it suited him; often, he would work the upper reaches of a painting from atop a set of portable steps.

Worth checking out.

Taster’s Cherce

Saveur gives us a recipe for Mugua Ji (sweet and sour chicken stir fry).

--Earl Weaver

![Spy[1]](http://www.bronxbanterblog.com/wordpress/wp-content/uploads/2012/01/Spy1-1024x768.jpg)

![shoulder_muscle_group[1]](http://www.bronxbanterblog.com/wordpress/wp-content/uploads/2012/01/shoulder_muscle_group1.jpg)