The old bastard will be missed.

He was one great Yankee.

The old bastard will be missed.

He was one great Yankee.

Our man William’s got it going on. Man, this brings back good memories.

After 13 seasons, Melvin Mora has decided to retire from baseball. The announcement, which was made last week, went largely unnoticed, but that’s not really much of a surprise. After all, most people probably didn’t even realize he was still playing (in 2011, Mora played 42 games for the Arizona Diamondbacks before being released at the end of June).

Never a superstar, Mora did have a very productive career, compiling 26.5 Wins Above Replacement and producing an OPS+ of 105, which isn’t too bad for a player who filled in at seven different positions during his time in the majors. What makes Mora’s career interesting, however, is not how he performed in the majors, but how long it took him to get there.

After eight seasons and over 3,000 plate appearances in the minor leagues, Mora finally got a taste of big league life in 1999. A product of the Houston Astros’ Venezuelan player development machine, Mora never blossomed in that organization, but a strong campaign with the Mets’ Norfolk affiliate that year finally helped earn him a promotion. Although Mora had to be ecstatic about finally getting to play, facing Randy Johnson in his first big league game may have had him rethinking all those years he toiled in the minors.

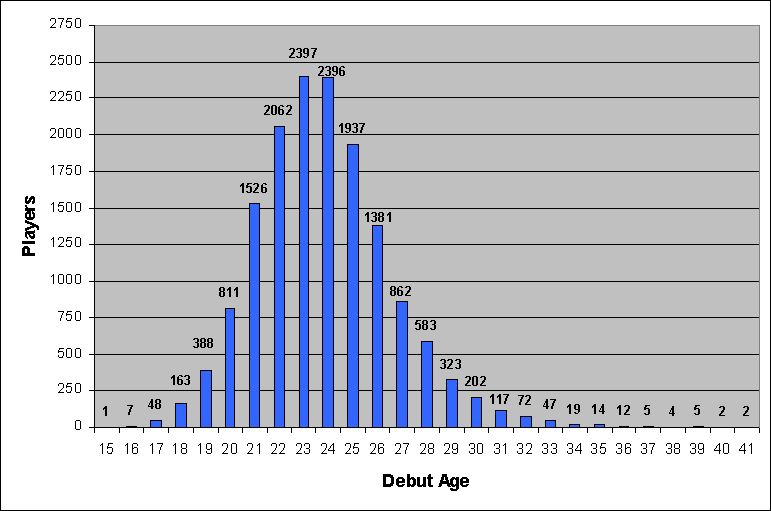

Distribution of Major League Debut Ages, Since 1901

Source: baseball-reference.com

Source: baseball-reference.com

When Mora played in his first game, he was already 27, which, by rookie standards, is rather long in the tooth. Since 1901, only 1,177 non-pitchers have debuted in the majors at that age or older, and just over one-quarter of that total lasted long enough to play a season’s worth of games. Mora defied the odds, however, and stuck around for 13 years.

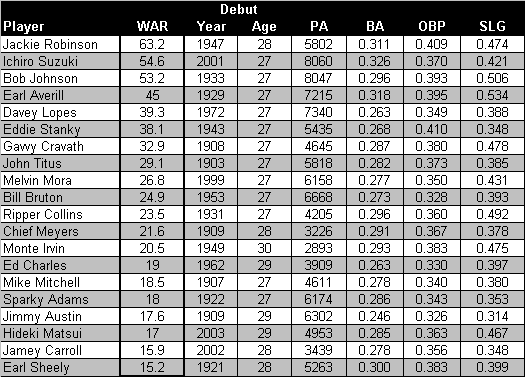

Among players breaking into the majors at age 27 or older, Mora ranks ninth in terms of cumulative WAR. At the top of the list is Jackie Robinson, whose debut was delayed by baseball’s color barrier, followed by Ichiro Suzuki, who got a late start in the majors because he previously spent nine seasons playing inJapan. Considering the extenuating circumstances pertaining to Robinson and Ichiro, Bob Johnson is more aptly considered the player who made the most of a late start. In 13 seasons following his promotion at the age of 27, Indian Bob posted a cumulative WAR of 53.2 during a career that featured seven All Star appearances. Who knows, had Johnson broken into the big leagues sooner, he could have end up as a Hall of Famer?

Late Bloomers: WAR Leaders Among Players Who Debuted At Age-27 or Older

Source: baseball-reference.com

At the other end of the spectrum is a player like Bob Lillis, who had the misfortune of being a short stop in the Dodgers’ farm system while Pee Wee Reese was going strong. In addition to be being buried on the depth chart, Lillis also had to contend with frequent injures, but, at the age of 28, he finally preserved by making the majors in 1958. Lillis actually had a very strong debut season, batting .391 in 69 at bats, but found himself now taking a back seat to new starting short stop Don Zimmer. After his first season, it was all down hill for Lillis, who ended up with an OPS+ of 55 and WAR of -6.9 over a career that spanned almost 2,500 plate appearances in 10 seasons. Apparently, good things don’t always come to those who wait, but at least Lillis qualified for the pension.

Lillis was lucky to stick around for so long because so many others in a similar situation were only given a fleeting glimpse of life in the majors. Moonlight Graham is probably the most famous case of such a player. At age 27, the right fielder finally got his big break, but it only lasted for 1 1/3 innings as a defensive replacement. Graham went on to become a doctor, and his story became immortalized on page and screen, but so many others had to be content with a page in the baseball encyclopedia (click here for list of players who appeared in one major league game). When you think about, even that’s not so bad, considering the thousands of career minor leaguers who would have given an arm and a leg (and some probably did) to join them.

Melvin Mora could have been one of those long suffering journeyman who never realized his dream. Instead, he is retiring after 13 productive seasons in the majors. Fortunately, Mora had the patience to wait for his chance, but it makes you wonder, how many others forfeited a big league career because theirs ran out?

Three days ago I received a package from Pat Jordan. Twenty pounds of pecans from the pecan trees in his backyard. Unshelled. The son of a bitch didn’t have the decency to include a nutcracker although he had a few suggestive hints how the wife and I could get them open. He did attach a note, however:

“To Whom it May Concern: Send pralines and pecan-bourbon pie to Susan and Pat Jordan, Abbeville, S.C. ASAP.”

My pal.

[Photo Credit: Simply Recipes]

Roger Ebert on “The Thin Man”:

Nick Charles drinks steadily throughout the movie, with the kind of capacity and wit that real drunks fondly hope to master. When we first see him, he’s teaching a bartender how to mix drinks (“Have rhythm in your shaking … a dry martini, you always shake to waltz time”). Nora enters and he hands her a drink. She asks how much he’s had. “This will make six martinis,” he says. She orders five more, to keep up.

Powell plays the character with a lyrical alcoholic slur that waxes and wanes but never topples either way into inebriation or sobriety. The drinks are the lubricant for dialogue of elegant wit and wicked timing, used by a character who is decadent on the surface but fundamentally brave and brilliant. After Nick and Nora face down an armed intruder in their apartment one night, they read about it in the morning papers. “I was shot twice in the Tribune,” Nick observes. “I read you were shot five times in the tabloids,” says Nora. “It’s not true,” says Nick. “He didn’t come anywhere near my tabloids.”

And Pauline Kael’s blurb:

Directed by the whirl-wind W.S. Van Dyke, the Dashiell Hammett detective novel took only 16 days to film, and the result was one of the most popular pictures of its era. New audiences aren’t likely to find it as sparkling as the public did then, because new audiences aren’t fed up, as that public was, with what the picture broke away from. It started a new cycle in screen entertainment (as well as a Thin Man series, and later, a TV series and countless TV imitations) by demonstrating that a murder mystery could also be a sophisticated screwball comedy. And it turned several decades of movies upside down by showing a suave man of the world (William Powell) who made love to his own rich, funny, and good-humored wife (Myrna Loy); as Nick and Nora Charles, Powell and Loy startled and delighted the country by their heavy drinking (without remorse) and unconventional diversions. In one scene Nick takes the air-gun his complaisant wife has just given him for Christmas and shoots the baubles off the Christmas tree. (In the ’70s Lillian Hellman, who by then had written about her long relationship with Hammett, reported that Nora was based on her.) A married couple, Albert Hackett and Frances Goodrich, wrote the script; James Wong Howe was the cinematographer. The cast includes the lovely Maureen O’Sullivan (not wildly talented here), the thoroughly depressing Minna Gombell (her nagging voice always hangs in the air), and Cesar Romero, Porter Hall, Harold Huber, Edward Brophy, Nat Pendleton, Edward Ellis (in the title role), and a famous wirehaired terrier, called Asta here. Warning: There’s a lot of plot exposition and by modern standards the storytelling is very leisurely. Produced by Hunt Stromberg, for MGM.

It’s the most cheerful drinking movie ever and one that is still a pure joy.

Dig Richard Sandomir’s piece on Mr. Met in the New York Times today.

Mr. Met has always given me the willies.

While you are at it, dig Larry Granillo’s Handy Dandy Mascot Guide over at Baseball Prospectus.

[Image Credit: Uni-Watch]

Hiroyuki Nakajima? Pass.

In 1974, when I was three years old, my grandparents returned from a trip to Florida with a gift for my mother and my aunt. They carried it in a box, a few small branches of an orange tree. My aunt planted hers and it died immediately but mom, who has a way with plants and flowers, potted the branch and it grew into a small bush. For years, it didn’t produce any fruit. Then, a few, small yellowish oranges appeared, too sour to eat.

Still, mom brought the orange tree with us when we left Manhattan and it survived a divorce, a new marriage, and five homes.

In a recent e-mail, she explained:

I had close-to-death encounters with this one: once going on vacation and finding it all dried up, I put a plastic tent over it and misted it to bring it back to life. Another time one of the cats peed in the dirt and nearly killed it. I had to wash the roots and repot the tree. I kept my fingers crossed on that one, I can tell you. Before we left Croton, a bug infestation, the tree got covered with scales. I hand picked the bugs and spay each leave on the top and on the bottom…

The tree survived and then flourished once mom moved up to Vermont two years ago.

I never knew you could eat the fruits. Then in a catalog recently, I read that a calamondin is a cross between a clementine and a kumquat.

This fall, as by conspiracy, the tree was covered with the biggest fruits ever. (The Vermont air and the Vermont compost…) So I decided to try to make marmalade. I added an orange to brake down the tartness of the calamondin, and bingo. Delicious, tart but nor sour, clementine-parfumed marmalade. The natural pectin in the fruit worked like a charm. All I needed was sugar and cute little pots.

She needed more than that. Patience, devotion, love. Mom’s got it. Got it in spades. It took close to forty years but she never gave up on her little plant, and I can’t wait to taste the marmalade.

Before I walk into an elevator I look up at the mirror. Force of habit from when I was a kid. Maybe “Dressed to Kill” got into my head. More likely, it’s a reflex I developed growing up in New York during a time when you expected to get mugged at any moment. I know it might be extreme now, but the mirror is there for a reason. When the elevator doors open I brace myself and look up at the mirror. Just in case.

Over in the New York Times, Tyler Kepner explains the Yankees’ approach this off-season:

It turns out the Yankees are not obliged to sign a player just because he happens to be a free agent who would fill a need. They won 97 games last season, the most in the league, before their first-round playoff loss. They can give it another try with these players and go back on the market next winter, when the free-agent starters should be much more appealing.

Cole Hamels and Matt Cain, All-Stars younger than 30 with strong postseason pedigrees, are unsigned past this season. Either would make more sense for the Yankees, in the long term, than [C.J.] Wilson or the other top starters on this winter’s market.

…What they are doing is planning ahead, a strategy that fits Hal Steinbrenner much better than it ever did his impatient father, George. Incentives in the new collective bargaining agreement would essentially reward the Yankees for reducing their payroll to $189 million by 2014. By then, Burnett, Mariano Rivera, Rafael Soriano and Nick Swisher will be off the payroll, which has exceeded $200 million in each of the last four years.

At the moment, the Yankees owe just over $80 million to Sabathia, Alex Rodriguez, Mark Teixeira and Derek Jeter for 2014. That leaves a lot of room for marquee talent, some of which is already in pinstripes.

This is all so sensible, though it feels odd on some level, a George-less Yankee team, one that exercises caution. Part of me is waiting for someone there to stop making sense–another Soriano maybe? In the meantime, they are being very Dude-like about it. Go figure.

In case you’ve never read it, here is Jonathan Lethem’s long 2006 James Brown profile for Rolling Stone:

To be in the audience when James Brown commences the James Brown Show is to have felt oneself engulfed in a kind of feast of adoration and astonishment, a ritual invocation, one comparable, I’d imagine, to certain ceremonies known to the Mayan peoples, wherein a human person is radiantly costumed and then beheld in lieu of the appearance of a Sun God upon the Earth. For to see James Brown dance and sing, to see him lead his mighty band with the merest glances and tiny flickers of signal from his hands; to see him offer himself to his audience to be adored and enraptured and ravished; to watch him tremble and suffer as he tears his screams and moans of lust, glory and regret from his sweat-drenched body — and is, thereupon, in an act of seeming mercy, draped in the cape of his infirmity; to then see him recover and thrive — shrugging free of the cape — as he basks in the healing regard of an audience now melded into a single passionate body by the stroking and thrumming of his ceaseless cavalcade of impossibly danceable smash Number One hits, is not to see: It is to behold.

The James Brown Show is both an enactment — an unlikely conjuration in the present moment of an alternate reality, one that dissipates into the air and can never be recovered — and at the same time a re-enactment: the ritual celebration of an enshrined historical victory, a battle won long ago, against forces difficult to name — funklessness? — yet whose vanquishing seems to have been so utterly crucial that it requires incessant restaging in a triumphalist ceremony. The show exists on a continuum, the link between ebullient big-band “clown” jazz showmen like Cab Calloway and Louis Jordan and the pornographic parade of a full-bore Prince concert. It is a glimpse of another world, even if only one being routinely dwells there, and his name is James Brown. To have glimpsed him there, dwelling in his world, is a privilege. James Brown is not a statue, no. But the James Brown Show is a monument, one unveiled at select intervals.

For more on James Brown, check out this piece by Chairman Mao.

[Painting by Ben Harley]

I was in Big City Records last week and listened this 45 by Paul Nice and the Diabolical One. And it made me happy.

Sunday at the Walter Reade Theater gives an evening with one of our heroes: Albert Brooks. Also a screening of his latest movie, the 2011 thriller, “Drive.”

Man, that sounds like a good time.

“From Williamsburg Bridge,” By Edward Hopper (1928)