A walk is as good as a hit. Even though some traditionalists might view such a statement as sabermetric hokum, that sentiment has been expressed by coaches from little league to the majors for who knows how many years. Of course, that doesn’t necessarily make it true. In many cases, a hit is much more valuable than a base on balls, but in terms of preserving precious outs, both are equally effective.

With the Rays in town, it’s the perfect time to examine the relationship between batting average and on-base percentage. Over the first two games of the current series at Yankee Stadium, the first two hitters in the Tampa lineup have been Ben Zobrist and Carlos Pena, whose relatively low batting averages make them seem like an unlikely pair to feature in the first two slots. Leave it to Joe Maddon to think outside the box, but, in this instance, his strategy isn’t very unorthodox. You see, Zobrist and Pena have two of the highest on-base percentages on the team.

Having a high on-base percentage despite a low batting average isn’t very common, but in Zobrist and Pena, the Rays have two of the top three hitters in terms of the differential between both rates (Zobrist is first at .152 and Pena is third at .150; Dodgers’ AJ Ellis is second at .151). Both hitters also rank among only 13 qualified batters who currently have an on-base percentage at least 150% greater than their batting average, so teams facing the Rays might be lulled into a false sense of security if they only focus on the latter.

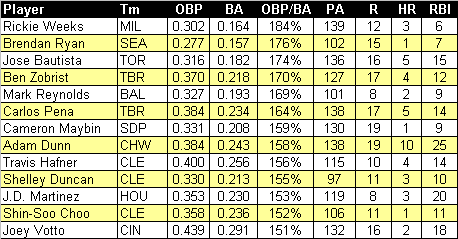

Hitters with OBP to BA Ratios of At Least 150%, Qualified Batters in 2012

Source: Baseball-reference.com

With an on-base percentage that is 184% of his batting average, Brewers’ second baseman Rickie Weeks has managed to salvage some value from the disappointingly slow start to his 2012 season. Like most of the members of the list above, his high ratio is mostly the result of having a subpar batting average. However, there is one standout. Reds’ All Star first baseman Joey Votto has piggybacked on a very respectable batting average of .291 with an on-base percentage that ranks fifth in the National League, which is par for the course for the former MVP, whose career ratio is 130% (.406 OBP vs. 312 BA).

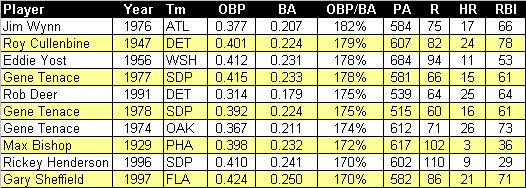

If Weeks maintains his current rates, he’d break the current on-base versus batting average differential record of 182% (based on qualified seasons), which was set by Braves’ outfielder Jimmy Wynn in 1976. That season, the Toy Cannon only hit .207, but, thanks to a league leading 127 walks, still finished in the top-10 in on-base percentage. In total, 175 players have had a qualified season with an OBP/BA ratio of at least 150%, but none has been more impressive than Barry Bonds’ 2004 campaign. That season, the homerun champion won the batting title with a .362 average and still managed to post a high multiple by reaching base in a remarkable 61% of all plate appearances.

10 Highest OBP to BA Ratios, Qualified Seasons since 1901

Source: Baseball-reference.com

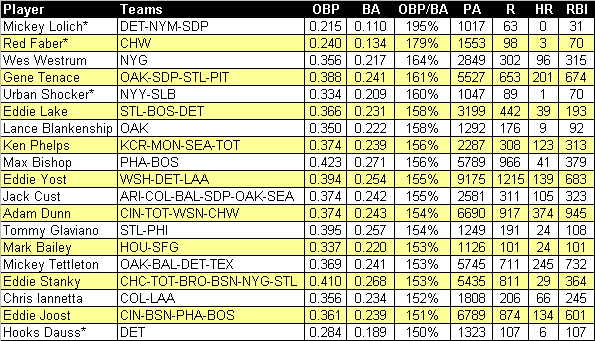

It’s hard enough for a hitter to reach base at a high multiple to his batting average in a single season, much less for an entire career. However, 19 players with at least 1,000 plate appearances have managed to turn the trick, and chief among them was Mickey Lolich. In his 16 major league seasons, which spanned the advent of the DH rule, the former Tigers, Mets, and Padres pitcher ended his batting career with more walks than base hits (105 to 90). As a result, Lolich’s on-base percentage was nearly double his batting average, a discrepancy that easily ranks as the widest in baseball history.

Hitters with Career OBP to BA Ratios of At Least 150%, 1901

*Indicates pitchers.

Note: Based on a minimum of 1,000 plate appearances.

Source: Baseball-reference.com

Among position players, West Westrum’s 164% multiple ranks as the largest differential, but the most impressive divergence probably belongs to Gene Tenace, whose on-base percentage was 161% higher than his batting average in over 5,500 plate appearances. Tenace, a catcher/first baseman whom some regard as a borderline Hall of Famer, ended his career with a very impressive OPS+ of 136, making him a prime example of a hitter capable of providing significant value over and beyond his relatively low batting average.

What about the other end of the spectrum? For a look at those hitters whose ability to reach base rests solely on their bats, join me for a companion piece over at the Captain’s Blog.

![steve_kerr[1]](http://www.bronxbanterblog.com/wordpress/wp-content/uploads/2012/05/steve_kerr1.jpg)