Hut, hut…

Picture via Kateoplis.

Dig this terrific profile of Angela Lee Duckworth by Marguerite Del Giudice over at National Geographic:

At the moment, Angela and her team are working on clever interventions to help students learn how to work hard and adapt in the face of temptation, distraction, and defeat. The total educational challenge is to accomplish this while at the same time steering them toward their passions, making sure they run around enough and enjoy childhood, and taking care not to inflict psychological damage.

How do you increase grit and self-control, not just in children but also in teachers and people in general, beyond just exhorting them to grin and bear it? Angela cites a current “big study” in and around Philadelphia in which randomly assigned students are asked to change their house or their bedroom in some way that would make studying easier. It could be as simple as having a better light in the room or putting their cell phones on a faraway shelf. If you want to start eating a healthful breakfast—oatmeal instead of a doughnut and coffee, say—you might decide to put the oatmeal out where you can see it first thing in the morning, take a route that doesn’t go by the Dunkin’ Donuts, or simply cover up any intrusive pastry with a napkin to make it less appealing. “Even young children know these tricks,” Angela says, “but adults sometimes forget them.”

These ideas, and her findings about hard work and persistence, are so plain and seemingly self-evident that Angela sometimes has a heck of a time getting across what a profound difference they could make in expanding human potential.

“It’s so simple,” she says, “that it’s hard to explain.”

At the University of Chicago, before a group of professors, she was asked why she studies perseverance. “Why?” she said. “Because life is hard. Because there are just obstacles every day to everything that we want to do. If it were easy, it would be done already, and I think that goes for any work that’s worthwhile.”

In our talent-obsessed culture, talent has been studied and is well understood. Perseverance? Not so much. Meanwhile, what college admissions officers and business leaders have told her they’re looking for these days from applicants is in keeping with her findings. It’s no longer students who’ve padded their résumés by doing a little bit of everything or just prospects with the best college grades; they want people who stuck with something meaningful to them over time and demonstrated some level of mastery, and it doesn’t necessarily matter in what. In a grit presentation by Skype with a group of educators from the Southwest that I sat in on, Angela quoted Martha Graham talking about what it takes for a mature dancer to make it look easy: “Fatigue so great that the body cries, even in its sleep” and—here’s Angela’s favorite line—”there are daily small deaths.”

In other words, children need to be taught to appreciate that they’re supposed to suffer when working hard on a challenge that exceeds their skill. They’re supposed to feel confused. Frustration is probably a sign that they’re on the right track and need to gut it out through the natural human aversion to mental effort and feeling overwhelmed so they can evolve.

[Photo Via PBS]

Can the Royals winning streak continue? Will the Cards tie up the NLCS?

Which one of these?

Let’s Go Base-ball!

[Photo Credit: Ed Zurga/Getty Images via It’s a Long Season]

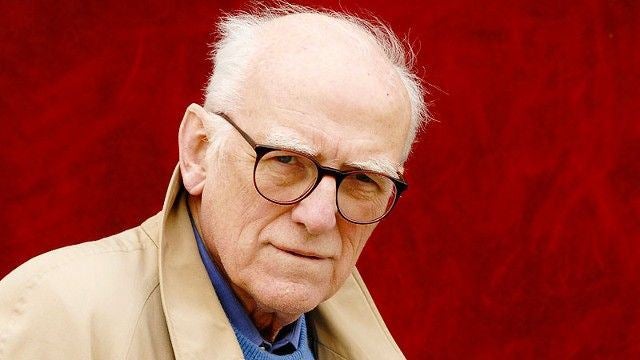

Donald E. Westlake (1933-2008) was one of our most prolific and entertaining writers. Now, we’ve got this posthumous treat: The Getaway Car: A Donald Westlake Nonfiction Miscellany, published by the University of Chicago Press and edited by Levi Stahl. The book is a ton of fun. I recently had the chance to catch up with Stahl. Hope you enjoy our chat.

Q: When did you start reading Donald Westlake?

Levi Stahl: I first encountered Westlake via Hard Case Crime: they published Lemons Never Lie, one of the novels he wrote under the name Richard Stark about the heister Parker’s associate Alan Grofield. I was impressed by it, but in that way that happens when you read a lot, I just kept moving and didn’t dig deeper.

Then on the day before Thanksgiving in 2007 I was at the office—and if you’ve ever been in the office the day before Thanksgiving (and don’t work for Butterball), you know that absolutely nothing happens. You’re there just in case something catches fire. That day, nothing was even smoldering, so at lunch I went browsing at my local bookshop, 57th Street Books, and plucked from the shelves what would end up being the penultimate Parker novel, Ask the Parrot. Back at my desk, I set to reading, and two hours later when my wife arrived for the long drive downstate to my parents’ house, I had to apologize: I had promised to do the driving, but now there was no way I could do any driving until I’d finished this book and found out what happened.

I was hooked. By Christmas I’d read ten or so Parker novels, all harvested from the used book market, and was making the case to colleagues at the University of Chicago Press that we should try to bring the series back into print. Now, almost seven years later, I’ve read all 100 of Westlake’s books—the Westlakes, the Starks, the Samuel Holts, the Tucker Coes, and the one-shots from Timothy Culver, Judson Jack Carmichael, Curt Clark, and even “The Vibrant J. Morgan Cunningham.” And almost all have been worth reading—even the couple that I would regard as truly weak offer some elements of interest.

Q: Damn, Westlake wrote 100 books? And you read them all? Man, that’s daunting. Okay, before we even get to the collection you’ve assembled, what Westlake titles would you recommend for someone who’s never read him before?

LS: The two series are an obvious starting point: trythe first Parker book, The Hunter, and the first Dortmunder, The Hot Rock. Neither is necessarily the best in the series, but they’re both quite good, and they give a clear sense of what these books are up to and whether you’ll like them.

From the standalones, I tend to recommend Somebody Owes Me Money, a hilarious first-person narrative from a put-upon cabby that opens, “I bet none of it would have happened if I wasn’t so eloquent”; Killing Time, an early, hardboiled work that is clearly in thrall to Hammett and Red Harvest but satisfying on its own terms; 361, a crime novel that was written deliberately with no explicit emotional signposts; God Save the Mark, a brilliantly funny collection of cons and nonsense; and The Ax, a 1997 hardboiled crime novel that is also a dissection of contemporary economic pain, as a laid-off print shop manager decides to kill the competition for the job he’d like to land. It’s so unrelenting it can be hard to read at times.

Q: Also, for the uninitiated, can you talk about the difference between Westlake’s two most famous protagonists?

LS: What may be more interesting about Parker and John Dortmunder is a relatively underappreciated quality that they have in common: they’re both extremely good at their jobs, yet their well-laid plans always go spectacularly wrong. The difference comes in how they respond to that. Parker, while remaining utterly emotionless, is bothered when a job goes sour, and he then takes whatever measures are necessary, up to and including extreme violence, to extricate himself from the problem, preferably with the loot. Dortmunder reacts to problems with an unsurprised shrug of his shoulders. Everything has always gone wrong for him, so why should this time be any different? Parker is an existentialist, Dortmunder is a fatalist.

Dortmunder actually emerged out of those very differences: Westlake started writing what he thought was another Parker novel, in which Parker and a gang have to try multiple times to steal a giant diamond. When he got to the third or fourth time the gang tried to steal the diamond, however, he realized he couldn’t keep going: Parker would have already cut his losses and moved on. But he liked the concept enough that he created a heister who would just keep plugging away at it, and with that, The Hot Rock started really rolling, and John Dortmunder was born.

The other big difference is that Dortmunder actually likes and cares about his gang. They’re almost as much friends as colleagues, and it shows in his willingness to continue to put up with their irritating, silly quirks. Parker, on the other hand, sees his colleagues as mere tools, useful yet, like all tools, prone to failure. So the one time he does truly extend himself for a fellow heister—risking his life, and the job, to save Alan Grofield in Butcher’s Moon, it astonishes not just the other guys on the string, but the reader, too. The Parker novels are popcorn, or shots of whiskey; the Dortmunders are chicken soup, or a PB&J. You go to them on different days, for different reasons, and they deliver what you’re looking for.

Q: Okay, to the collection that you’ve edited. How did this project come about?

LS: I discovered Westlake the nonfiction writer via Trent Reynolds’s excellent Violent World of Parker site. He had posted a scan of an Armchair Detective article from the early 1980s that reproduced a talk Westlake had delivered at the Smithsonian about the history of hardboiled private eyes in fiction. That piece revealed Westlake to be a serious thinker about and critic of the crime genre, and it made me wonder what else he might have written. Quick searching turned up enough to build a book proposal, deeper library research fleshed it out nicely, and—best of all—a trip to the Westlake house to go through his files, courtesy of the endlessly gracious Abby Westlake, turned up a bounty of little-known and never-before-published pieces.

Q: With a guy as prolific as Westlake, how did you decide what to choose from—not only single pieces—but categories?

LS: The categories actually came last, when I looked at my giant stack of papers and realized, belatedly, that I would need to put them in some sort of sensible order. But once I started doing that, making stacks of pieces on Westlake’s own work, of pieces on other writers, of letters, etc., the very act of sorting helped me figure out whether I wanted to include the couple of pieces that were on the bubble. For example: you could probably do a whole book of Westlake interviews, but once I gathered what I had, it became obvious that the two I should include were the ones that focused largely on his film writing career, as most of the other topics that come up in interviews (his life and his books) were covered elsewhere.

My early readers, Charles Ardai of Hard Case Crime and Sarah Weinman, editor of Troubled Daughters, Twisted Wives, were also extremely helpful: seeing what pieces interested these two genre experts most, and which were less effective, helped to transform the early manuscript into something more compact and potent. The only piece that I knew from the very start had to be in the place it is was the final letter. The moment I read it, pulled from Westlake’s filing cabinet, I knew I had the last words of the book.

Q: Westlake’s generosity toward his peers—Rex Stout, Charles Willeford, even a review of a George Higgins novel come to mind—is admirable. He seemed not motivated by professional envy but professional admiration. I like the note he tacked up at his desk, NO MORE INTRODUCTIONS, but the truth is, he was very good at writing them, wasn’t he?

LS: He really was an astute and generous critic of other writers. His essay on Peter Rabe, whom he greatly admired and acknowledged was a huge influence, is the perfect example. In the book that section opens with a letter from Westlake to Rabe telling him he’s going to be writing about his work and asking some questions; the letter is appreciative, funny, and generous, and Rabe responded enthusiastically. However, knowing that Rabe would eventually read the essay clearly didn’t stop Westlake from offering strong criticism of his weaker books—but at the same time, the admiration for Rabe’s achievement is so strong, clear, and well grounded in detailed analysis that the overall effect is to make you come away wanting to read more of Rabe’s books. Ultimately, that’s the effect of all of Westlake’s introductions: it’s the job of the person writing the introduction to make you see what’s special about the writer being presented, and Westlake was spectacularly good at that.

Another example of his ability to analyze and offer criticism of crime fiction is the letter to David Ramus. Ramus had—I’m not sure through what channel—sent Westlake the manuscript of what would become his first novel, On Ice. I don’t know what he was expecting, but what he got was a detailed examination of what did and didn’t work in the book, with suggestions of how things could be done better—suggestions given, explicitly, not to say that Westlake’s way was right, but that another way was possible. The letter, and the investment of time it represents, is an act of stunning generosity. The most entertaining moment in that letter? “Finally, I have one absolute objection. We do not overhear plot points. No no no.”

Q: Can you describe how he used humor in his books? His wife said he wasn’t jolly in real life, but witty, loved to laugh and loved making people laugh.

LS: In his foreword to this book, Westlake’s friend Lawrence Block takes issue with my characterizing Westlake’s writing as being filled with jokes. It’s wit, rather than jokes, says Block, and I think he’s basically right. Perhaps the biggest thing I took away from my time researching this book was that Westlake hardly ever wrote a full page of anything—be it fiction or a business letter—without finding a way to get some humor into it. He just seems to have seen the world that way: everything is a tiny bit ridiculous, because, well, look at us? We’re not really very good at this living stuff, are we? Yet we have the audacity to make plans and think we’re in control. That illusion is the source of so much of Westlake’s humor. Everything is always going wrong, and that in and of itself is funny, if you look at it the right way. As he put it in his piece on Stephen Frears, “If we aren’t going to enjoy ourselves, why do it?” He really seems to have written, and lived, with that motto in mind.

Q: The most delightful surprise in the book is the chapter on the Goon Show, the British radio comedy hit that was the precursor to the Pythons and Beyond the Fringe.

LS: Wasn’t that unexpected? Westlake was a comic writer, obviously, but like you I was still surprised to find him writing about the show, and weaving his appreciation of it into a short autobiographical essay. I’d thought a lot about his genre forebears and influences, but I’d never given the same thought to the influences on his comedy.

Q: What did you find that surprised you?

LS: For me the biggest surprise was more structural: I knew that Westlake had written for Hollywood, but it wasn’t until I was going through his files that I realized what a big part of his work, and income, it was. Even as he was writing 100 books, he was also turning out screenplays, and treatments, and pilots, and rewrites, most of which never made it to the screen. That was a big reason why I wanted to include the two interviews that focused on film, and the piece on Stephen Frears: it’s a side of Westlake that I think even those of us who are big fans don’t necessarily know about. (My only regret with the book, meanwhile, is that I couldn’t find a way to work in even a single reference to Supertrain!)

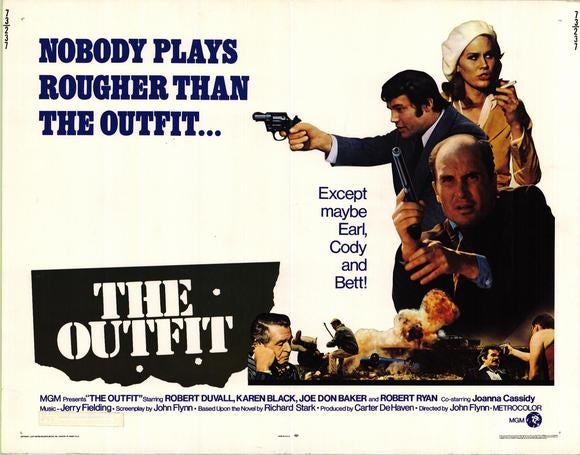

Q: What were Westlake’s experiences with Hollywood like? Several of his books were made into movies, some of them good—The Hot Rock, Point Blank. I didn’t know it at the time but I first remember seeing his name in the credits for The Grifters and a very good, creepy movie, The Stepfather.

LS: He worked hard with Hollywood and drew a substantial part of his income from there throughout his life. But he always seems to have held it at arm’s length. You get the feeling that the loss of control and independence that working with Hollywood, even in the relatively isolated role of screenwriter, required sat awkwardly with Westlake’s lifelong iconoclastic, individualistic, rebellious streak. There’s a reason that he didn’t like, and didn’t stick in, the Air Force; that same reason seems likely to be why Hollywood never truly seduced him.

Q: In a letter, Westlake described the difference between an author and a writer. A writer was a hack, a professional. There’s something appealing and unpretentious about this but does it take on a romance of its own? I’m not saying he was being a phony but do you think that difference between a writer and an author is that great?

LS: I suspect that it’s not, and that to some extent even Westlake himself would have disagreed with his younger self by the end of his life. I think the key distinction for him, before which all others pale, was what your goal was: Were you sitting down every day to make a living with your pen? Or were you, as he put it ironically in a letter to a friend who was creating an MFA program, “enhanc[ing] your leisure hours by refining the uniqueness of your storytelling talents”? If the former, you’re a writer, full stop. If the latter, then you probably have different goals from Westlake and his fellow hacks.

But does a true hack veer off course regularly to try something new? Does a hack limit himself to only writing about his meal ticket (John Dortmunder) every three books, max, in order not to burn him out? Does a hack, as Westlake put it in a late letter to his friend and former agent Henry Morrison, “follow what interests [him],” to the likely detriment of his career? Westlake was always a commercial writer, but at the same time, he never let commerce define him. Craft defined him, and while craft can be employed in the service of something a writer doesn’t care about at all, it is much easier to call up and deploy effectively if the work it’s being applied to has also engaged something deeper in the writer. You don’t write a hundred books with almost no lousy sentences if you’re truly a hack.

Q: I loved the piece that Westlake’s wife wrote about his working habits.

LS: Isn’t it great? In her tongue-in-cheek, yet insightful essay “Living with a Mystery Writer,” Abby Adams Westlake talks about the differences she would see in her late husband depending on which of his many personas he was writing as. In discussing his Timothy J. Culver pen name, she describes his writing set-up:

“His desk is as organized as a professional carpenter’s workshop. No matter where it is, it must be set up according to the same unbending pattern. Two typewriters (Smith Corona Silent-Super manual) sit on the desk with a lamp and a telephone and a radio, and a number of black ball-point pens for corrections (seldom needed!). On a shelf just above the desk, five manuscript boxes hold three kinds of paper (white bond first sheets, white second sheets and yellow work sheets) plus originals and carbon of whatever he’s currently working on. (Frequently one of these boxes also holds a sleeping cat.) Also on this shelf are reference books (Thesaurus, Bartlett’s, 1000 Names for Baby, etc.) and cups containing small necessities such as tape, rubber bands (I don’t know what he uses them for) and paper clips. Above this shelf is a bulletin board displaying various things that Timothy Culver likes to look at when he’s trying to think of the next sentence. Currently, among others, there are: a newspaper photo showing Nelson Rockefeller giving someone the finger; two post cards from the Louvre, one obscene; a photo of me in our garden in Hope, New Jersey; a Christmas card from his Los Angeles divorce attorney showing himself and his wife in their Bicentennial costumes; and a small hand-lettered sign that says ‘weird villain.’ This last is an invariable part of his desk bulletin board: ‘weird’ and ‘villain’ are the two words he most frequently misspells. There used to be a third—’liaison’—but since I taught him how to pronounce it (not lay-ee-son but lee-ay-son) he no longer has trouble with it.”

In an interview conducted by Albert Nussbaum, Westlake went into a bit more detail about his approach:

“If I work every day from the beginning of a book till the end, my production rate is probably three to five thousand words a day–unless I hit a snag, which can throw me off for a week or two. But if I work every day I don’t do anything else, because everything else involves alcohol; and I don’t try to work with any drink in me, so in the last few years I’ve tended to work four or five days a week. But that louses up the production two ways; first in the days I don’t work, and second, because I do almost nothing the first day back on the job. This week, for instance, I did one or two pages monday, five pages Tuesday, five Wednesday, fourteen Thursday, and three so far today.” He went on to say that he used to complain to his second wife, “I’m sick of working one day in a row!”

Q: Craft was central for Westlake. In some ways, his Parker books are an appreciation of craftsmanship, aren’t they?

LS: When I first started reading the Parker books, what struck me was that they were essentially books about work. In the first one I read, Ask the Parrot, Parker sets up a hidey-hole in an empty house, carefully sawing off some screws in the wood that’s boarding it up so that he can get in and out easily without being detected. The activity is described in detail, and I’m pretty sure Parker doesn’t ever end up needing the hideout. But it was part of doing the job (in this case, the job of staying alive after a failed heist), so Westlake included it. (I wrote a bit about the Parker novels as books about work on my blog way back in December of 2007.)

Luc Sante, in his foreword for some of Chicago’s Parker editions, put the same point this way:

“Westlake has said that he meant the books to be about ‘a workman at work,’ which they are, and that is why the have so few useful parallels, why they are virtually a genre unto themselves. Process and mechanics and troubleshooting dominate the books, determine their plots, underlie their aesthetics and their moral structure. . . . Parker abhors waste, sloth, frivolity, inconstancy, double-dealing, and reckless endangerment as much as any Puritan. He hates dishonesty with a passion, although you and he may differ on its terms. He is a craftsman who takes pride in his work.”

There’s a passing line in The Man with the Getaway Face that has stayed in my head for seven years now: “When the mechanic came in at seven o’clock, he looked at the truck in disgust. He got interested, though, being a professional, and worked on it till nine-thirty.” That’s what a professional, a craftsman, is: a person who actually cares about, and becomes deeply engaged with working his best at, the job at hand.

[Photo Credit: Pictures of Westlake via Omnivoracious and Grantland; Drawing by Darwyn Cooke]

From the funtastic new book, The Getaway Car: A Donald Westlake Nonfiction Miscellany, check out this short essay Westlake wrote about working with Stephen Frears.×

Westlake wrote a screenplay based on Jim Thompson’s The Grifters for Stephen Frears’s acclaimed 1990 film adaptation, which ended up receiving four Academy Award nominations, including one for Best Screenplay. This essay was published in Writers on Directors in 1999.

Here are two things Stephen Frears said to me. The first was several months before The Grifters was made and, in fact, before either of us had signed on to do the project. We had just recently met, brought together by the production company that had sent us to California to look at the place. Driving back from La Jolla toward L.A., me at the wheel of the rented car, Stephen in the seat beside me musing on life, he broke a longish silence to say, “You know, there’s nothing more loathsome than actually making a film, and it’s beginning to look as though I’ll have to make this one.” The second was the night of the same film’s New York premiere, at the post-opening party, when he leaned close to me in the noisy room and murmured, “Well we got away with it.”

I think what attracted me to Stephen in the first place is that, in a world of manic enthusiasm, here at last I’d met a fellow pessimist. Someone who would surely agree with Damon Runyon’s assessment: “All of life is six to five against.”

Not that he’s a defeatist, far from it. For instance, he refused to let me turn down the job of writing The Grifters, a thing that never happens. The normal sequence is, a writer is offered a job, thinks it over, says yea or nay, and that’s that. Having been offered this job, I read Jim Thompson’s novel—or reread, from years before—decided it was too grim, and said nay. That should have been the end of it, but the next thing I knew, Frears was on the phone from France, some Englishman I’d never met in my life, plaintively saying, “Why don’t you want to make my film?” I told him my reasons. He told me I was wrong, and proceeded to prove it—”It’s Lilly’s story, not Roy’s,” was his insight, not mine—and I finally agreed to a meeting in New York, which was the beginning of the most thoroughly enjoyable experience I’ve ever had in the world of movies.

Here’s another thing Stephen said to me: “I like the writer on the set.” This is not common among directors, and I wasn’t at all sure what it meant. Did he want a whipping boy? Someone to hide behind? Someone to blame? (You can see that I too am not a manic enthusiast.)

Anyway, no. As it turned out, what he wanted was a collaborator, and what we did was a collaboration. I didn’t direct and he didn’t write, and between us both we licked the platter clean.

I am not a proponent of the auteur theory. I think it comes out of a basic misunderstanding of the functions of creative versus interpretive arts. But I do believe that on the set and in the postproduction process the director is the captain of the ship. Authority has to reside in one person, and that should most sensibly be the director. So my rare disagreements with Stephen were in private, and we discussed them off-set as equals, and whichever of us prevailed—it was pretty even—the other one shrugged and got on with it.

The result has much of Jim Thompson in it, of course. It has much in it of the talents of its wonderful cast and designer. It has some of me in it. But the look of it, the feel of it, the smell of it, the three-inches-off-the-ground quality of it; that’s Stephen.

If we aren’t going to enjoy ourselves, why do it? Stephen’s right, much of the filmmaking is loathsome. Pleasure and satisfaction have to come from the work itself and from one’s companions on the journey. The Grifters was for me that rarity; everyone in the boat rowing in the same direction. I hadn’t had that much fun on the job since I was nineteen, in college, and had a part-time job on a beer truck with a guy named Luke.

The Getaway Car is on sale now.

[Copyright Donald E. Westlake. Reprinted with permission from The Getaway Car: A Donald Westlake Nonfiction Miscellany, published by the University of Chicago Press. All rights reserved.]

Paul Newman had been a star for more than two decades when he went on fantastic run. It might not be his best string of movies, but starting in 1977 with Slapshot and lasting through The Color of Money in 1986, Newman delivered some of his most impressive work in movies like Fort Apache, the Bronx; The Verdict; and Absence of Malice.

In her review of Slapshot, Pauline Kael wrote:

“Newman is an actor-star in the way Bogart was. His range isn’t enormous; he can’t do classics, any more than Bogart could. But when a role is right for him, he’s peerless. Newman imparts a simplicity and a boyish eagerness to his characters. We like them but we don’t look up to them. When he’s rebellious, it’s animal energy and high spirits, or stubbornness. Newman is most comfortable in a role when it isn’t scaled heroically; even when he plays a bastard, he’s not a big bastard—only a callow selfish one, like Hud. He can play what he’s not—a dumb lout. But you don’t believe it when he plays someone perverse or vicious, and the older he gets and the better you know him, the less you believe it. His likableness is infectious; nobody should ever be asked not to like Paul Newman.”

His last great performance came a few years later in Robert Benton’s adaptation of Richard Russo’s wonderful book, Nobody’s Fool.

That’s when our man Peter Richmond—whose terrific first YA novel, Always a Catch, was published a few weeks ago—caught up with him. This piece first appeared in the January 1995 issue of GQ and appears here with the author’s permission.

—Alex Belth

He answers the door in slippers, a polite and questioning half-smile set off by tortoiseshell bifocals perched on the bridge of his nose. He offers toast in the kitchen of his prewar penthouse late on a Sunday morning when the New York autumn is chilled by October showers and the sky is as absent of color as the froth of hair on top of his head. He is slicing a stick of butter, very carefully, with a serrated knife, peering over his spectacles so as not to cut off his fingertips. He is talking about the weather.

“I love it,” he says. “I just think the cold is blissful”—a pause for an inside-joke smile—“in my antiquity.”

It would seem, at best, an uneasy fit: Paul Newman and his seventieth birthday, this month. But spend more time with him and it’s clear that the man and the age are a good and comfortable match.

Eddie Felson, Cool Hand Luke, all the cons in search of the angle—maybe they’d fight it, fighting the roll of the seasons. But Paul Newman—who now, finally, is none of these people—is clearly at home with his current circumstance: as no one but himself.

You knew him for the color of his eyes and the chiseled perfection of his torso, but in fact you knew nothing but the way Paul Newman looked. You have never been on familiar terms with Paul Newman the symbol, the symbol of whatever it was you wanted him to be: the defiant youth, perhaps, but without the darker currents of James Dean, or the outcast, but without the bluster of Brando, or, eventually and most memorably, the cad thief or villain eternally redeemed by a beatific smile.

But he is no symbol now. Paul Newman’s physical presence is no longer overwhelmingly compelling, a fact that leaves us—and him—with much more of the essence of the man. In his new movie, the story of nothing but the quiet emotions of an aging man, his looks are irrelevant, and he seems entirely suited to the role.

***

He does not pretend to have all of the answers. Questions remain. He asks them gently, in a low voice, using measured words and separated by long pauses, all of it punctuated by frequent glances at the rain patting the terrace outside the living-room windows.

“I am thoroughly and predictably concerned about what was my accomplishment and what was the accomplishment of my appearance, which I have no control over,” he says. “What was attributable to me? And what is the difference between a truly creative artist and an interpretive artist? I have not concluded anything about that, but it’s fair to ask the question.”

It’s not the usual rope-skip one expects from people of note who deign to cede a few minutes of their days to an interviewer. This is a deliberative conversation, and he tries to get as much meaning into as few words as possible. He’s never had any love for the interview process, but he is nonetheless polite enough to want to convey something substantial in a short time. Envision, if you can, a weight attached to every phrase.

“And everybody shakes their head and says ‘Oh, isn’t it too bad that he doesn’t enjoy…more of a sense of accomplishment,’ and so forth,” he continues. “But it’s not a false sense of modesty or self-deprecation. It’s really just looking at it and saying ‘Where did it come from? What do you owe it to?’”

So it should come as no surprise that the definitive question Paul Newman poses about his life is whether an entire career was forged on the pigment of his eyes.

“You’re constantly reminded,” he says. “There are places you go and they say ‘Take off your dark glasses so we can see your beautiful blue eyes.’ And you just want to…you just want to…I dunno, um…thump them.”

He holds up his right hand—“A short chop right above the bridge of the nose”—and gives up a laugh.

“They could say, ‘Hey, its very nice to meet you’—that’s great. Or ‘Thanks for a bunch of great performances,’ and you can feed off that for a week and a half. But the other thing, which is always there, is a never-ending reminder.”

The eyes. He proposes that if we insist on putting his picture on GQ’s cover, we eschew the usual mug of shot and run one simply of his eye. His right eye. Close up. Just the eye.

“This bloodshot blue eye,” he says, and he laughs. And then he says, “Or take the engine out of a stock Ford. Have the hood up. I’ll just be sleeping in there.”

The last is not a non sequitar. It’s an allusion—a comic allusion—to an arena in which Paul Newman answered the question of how much of his success was due to talent and hard work. He was a champion race-car driver. He was good at driving; his looks didn’t matter. But that time is over now, too. Newman raced just once last year. The previous year, he’s raced in six events and crashed in five of them.

“Driver error,” he says now. “The teeth get longer. The hair gets thinner. The eyes and ears don’t sense danger as quickly as they did before. You can’t go fast, so you try and go faster.”

Madness lies that way, of course. And so on a Sunday morning when two years ago he might have been up on the track at Lime Rock, in Connecticut, he’s wending his way through The Times instead. His wife is in another part of the apartment, listening to opera. An aria winds out of the room and finds us. Newman falls silent; the conversation pauses.

But it is the most welcome of silences, too; fifteen stories above the Central Park reservoir, amid books and family photographs and very old paintings. It is so peaceful that time feels if it’s not even passing.

“Bette Davis said it best of all: ‘Getting old ain’t for sissies,’ “he said eventually. “I mean—suppose, to do it right, it ain’t for sissies.”

How do you do it right?

“Stay in the thick of it, I guess…I’ve been working on this thing on and off for seven years.”

I need a moment to make the connection: The “thing” is his current project—not Nobody’s Fool, the movie just out, but the next one—he assumes that I know what he’s talking about because it’s on his mind all of the time; it’s what binds his professional life now. It’s the script he’s been writing for the past year and a half. The film he’ll direct.

The writing is what drives him. It’s easier than getting in front of the camera, where the way he used to look has become an issue. “Which is part of why I’m directing this next film,” he says. “I don’t have to worry about it. I wouldn’t worry about it. But other people worry about it. And I’m at that point where…it just takes too much effort.”

***

They never seemed effortless, the men in Paul Newman’s catalogue. They were all highly complicated, not a flat-out, clear cut hero among them—pool hustler, grifter, alcoholic lawyer and now, in Nobody’s Fool, a man who abandoned his family because it was the easy thing to do. They were flawed and beautiful men in circuitous search of redemption, and Newman wore the characters effortlessly.

This was not luck or fortuitous casting. He did the foundation work for years, on the stage and in bad films, but so did any number of pretty young men. What Newman brought to the screen, what allowed him to blossom, was his ability to make Hud and Harper and Fast Eddie so familiar. So identifiable. Their troubles were always, somehow, real.

“I had some troubling years,” Newman says.

Newman did what many young men do. He drank; he fought. He should have known better, he says now. After combat duty in the Pacific, he put in four years at Kenyon College and a year at Yale Drama. He was kicked off the football team at Kenyon for taking part in a tavern rumble between college kids and townies—a particularly embarrassing episode, given that Newman hadn’t even been rounded up with the original arrestees; it was only when he showed up at the jail to give the quarterback his car keys that a cop saw the second-stringer’s scuffed knuckles and locked him up, too. Several years later, there was an arrest for leaving the scene of an accident in which no one had been hurt. “A mistake,” he admits. “Dumb.”

“I barely made it in my time,” he says. “And don’t forget that the acceleration of everything was much slower. We only had booze in our day—which was bad and ugly enough. We didn’t have crack.”

In the kitchen, two empty beer cans stand upside down, side by side, in the dish rack, rinsed for the recyclers—aligned in orderly fashion, in defiance of any hint of impropriety.

Did his drinking ever come close to derailing what he had going?

After a moment’s thought, he nods and nods and nods. The silence stretches on and on. Then he says, “Fortunately, that was back in the Stone Age.” Silence again. “So.”

It is neither the time nor the place to ask for elaboration. Not in Paul Newman’s living room. That is a given. The overriding theme of the hundreds of interviews Newman had granted is his discretion. He saves a special disdain for the public’s gutter curiosities. Several years ago, amid the flowering of tabloid journalism, Newman announced that he’d adopted a personal theme: Fuck Candor.

***

His father was the successful proprietor of a sporting-goods store in Cleveland, and when Newman speaks of him, it is with respect for nothing so much as Arthur S. Newman’s integrity: “In the Depression,” he says, leaning a little closer over his coffee, “[he] got $200,000 worth of consignment from Spalding and Rawlings because [his] reputation for paying, [his] honesty, was so impeccable.” Arthur Newman, his son says, was many things: ethical, moral, funny. And distant. Newman once spoke of his anger and frustration at never being able to earn his father’s approval.

He met and married his first wife, Jacqueline Witte, in 1949, when they were members of an acting troupe in Illinois. Upon his father’s death, in 1950, Newman moved his wife and infant son back to Cleveland but couldn’t put his heart into selling sports goods. He turned the business over to his brother and took his family to New Haven, for his year at Yale; soon afterward, he was working in New York. But his ascent on the stage coincided with a muddying of emotional waters: He met Joanne Woodward in 1952, worked with her frequently and found himself being pulled toward her. Newman and Jacqueline had three children by the time they divorced. In 1958, he married Woodward, and they subsequently had three daughters of their own. His career took flight.

In 1978, Scott Newman, his 28-year-old son, died of an accidental drug and alcohol overdose. The family endowed a drug-education foundation in his name. Several years later, Newman started a Connecticut camp for seriously ill children, and now his charity work had become the stuff of legend. He has gone into the food business and has been wildly successful in it. It’s typical refutation by Newman the person of Newman the Hollywood icon: Matinee idol joins the merchant class.

“I worked in the [sporting goods] store every Saturday as a kid,” he says. “And now I’m hustling salad dressing. What is the circularity of things?”

But the answer doesn’t seem too difficult to divine. The success of his food endeavor made Newman a businessman of good refute—someone his father could admire—and by donating his considerable profits ($56 million, so far) to various charities, he has equaled his father’s reputation for integrity.

More: He derives genuine pleasure from watching something he created flourish. “I can understand the romance of it,” he says. “Where you create something. It’s kind of like writing, in a way…where you say [to your creation] ‘Just stay right there’ and it says ‘I got other plans,’ and it goes shooting off in other areas. And you say ‘Look at that little fucker go.’ “

Clearly, the greatest joy he derives from the business these days is in designing the labels—fanciful, nonsensical, joyous paeans to the simple goodness of good food, Whitmanesque in spirit: “Terrifico! Magnifico…share with guys on the streetcar…ah, me, immortal!”

He writes the copy himself. On the new Caesar salad-dressing bottle, the government has co-opted three-fifths of his label for the mandatory nutritional data, robbing him of the space needed for what he wanted to write—an apocryphal story of the time he played Caesar at a regional theater and how, after he was stabbed, an offstage phone rang and another actor ad-libbed “I hope it wasn’t for Caesar.” Instead, he settled for a sketch of the morally wounded emperor, a bloody dagger pointing to the ingredients, and Caesar saying “Don’t dilute us, Brutus.”

Newman laughs at that one. Then he pauses again. Half of the morning in pauses.

Writing—the next movie, the labels—is a sensible thing for a man grown distrustful of the camera to do. He has found, in the scripting of a very personal film, a new creative surge. “I could have given up on this thing,” he says, “a long time ago.”

Did people tell him to?

“Oh boy—writers and friends. But I really am pleased with it. The way it turned out. It has the same kind of emotional progression as Nobody’s Fool. But much more personal.”

Nobody’s Fool is personal, too. As written, the character of Sully—an underachieving, good-natured, down-on-his-luck handyman in a depressed, snow-locked upstate-New York town—allowed for a great deal of invention on Newman’s part. “There wasn’t a tremendous amount of plot progression,” he admits. “[I] had to create the progression of where he was emotionally.”

In giving Sully a life, he gave the character some of his own life. And after a couple of intentionally over-the-top roles—Governor Earl Long in Blaze, a corporate shark in The Hudsucker Proxy—he may have finally come up with a way to quiet his own questions about how much of his success is the result of a craft he worked hard to perfect.

At first glance, Sully appears to be a man who finds a small nobility in living a life that requires nothing but getting through each day with his circle of small-town friends. But his story is tangled when, by chance, he meets the son he abandoned when the boy was a year old and the grandchildren he’s never met and has never particularly wanted to meet. Thereafter he is forced to examine his life: simple and reassuringly placid on the surface but rooted in irresponsibility and neglect. Sully decides to face the truth of what his negligence has sown. And to make amends.

“His bravery,” Newman says, “was that he was at that point in his life when he did not want to…deny it anymore. He no longer tries to keep his own…accessibility…away from himself. [He finally] accepts his sense of family. And the incredible magnetism of that.

“I don’t know whether the audience will get that,” he says. “They may get something else. I don’t know that they’ll get all of the things this film means to me…[the] secrets between me and the character. They are tiny discoveries. And they’re mine. I don’t know if they’ll be visible.”

It is an oblique soliloquy. The gist of it seems to be that in Sully, Paul Newman had finally found a man who has made the right decision: to face himself in his waning years.

I begin to observe that it sounds as if Sully is in microcosm what Newman himself…but that is as far as I get.

“Yeah,” he says, interrupting me. “Painfully close. As this next film will be.”

His wife has taken the dog for a walk. The radio is silent. The rain has stopped. The coffee is cold.

“The nice thing about the picture was that you didn’t have to discover where the money was—you had to discover where he was,” Newman says. “It’s an examination of the good in ordinary people. But maybe in order to be good [in movies] you have to kill 53 people. Used to be you only had to kill three or four. Now everything has escalated. The insistence on sexual, visceral gratification has become so intense…The human animal is an escalating beast.”

His expression makes it obvious that he is reluctant to be led into this old swamp, into routine condemnation of the modern age, but it would hardly be right to talk with Paul Newman without getting his take on the social pulse. He was a Connecticut delegate in the Democratic National Convention in 1968 and a member of a U.S. delegation to a 1978 United Nations session on disarmament. He was No. 19 on Nixon’s enemies list. But his activism has since been reined in. “The Sixties—I had to have my foot in everything then,” he says. “I’m doing the same thing now but through an intermediary. You know. The food company. Maybe that’s the way to go about it. You go right straight into the inferno, and when you get older, you pull back. You don’t really give up your responsibilities, but you find some less exhausting way.”

Still, when he’s led into conversation about the mores of our time, his hands tap a drumbeat on the arms of his antique wooden chair.

“It’s kind of like those little electric bumper cars where you drive around and see if you can hit the other guy. That’s exactly what the country is like now. You no longer have the sense of community. Of loyalty. It’s lost its sense of group. It has nothing to do with leadership. Everybody’s out there alone, getting his own whacks. Instead of deifying the community, they’ve deified the individual. Maybe that’s necessary in principle. In the Bill of Rights. But… ‘What’s good for the individual is good for the country’? It simply is not true. What is good for the community is good for the country. Once you put the individual on a pedestal, it’s at the expense of everything else.

“What I would really like to put on my tombstone is that I was part of my time,” he says. “And that I’m, satisfied with that. And that’s comforting. I did okay. It’s been good. It’s nice to finally…get it as you get into your mid-sixties. It’s better than not getting it at all. And I have seen a lot of people who go to their graves without ever…without ever getting in touch with what it is that’s the core of them. It’s very easy as an actor…you can just walk around as Hud all day long, have people marvel at your grace, your manliness, your quick-wittedness. [But] it all eats away at whatever is at the core of…your own humanity. At getting in touch with that, and being satisfied with it, and comfortable.”

Being satisfied. Being comfortable. Getting it. We’re talking about him now, right?

“Yeah,” he says.

A moment later, en route to the elevator, he amplifies. Only a bit. But enough.

“I don’t have to worry,” he says, “about being something for somebody.”

The other half of the thought doesn’t need to be spoken: Now it’s time to be him for him.

Which is why, finally, the smile at the end of the morning—back at the apartment door, in the foyer, the elevator summoned—is different from the one that greeted me. It’s not just on his lips. It’s in his eyes.

The difference is not in their color. Their color is just sort of pale-blue.

It’s the light behind them. Maybe the light I want to see behind them. The light I do see behind them. The particularly brilliant light of winter.

[Photo Credit: Toni L. Sandys]

Alexandra gives roasted acorn squash with maple butter.

One of the most dramatic changes in this blog over the past 5 years has been visual. I use far more images–drawings, paintings, photographs–than I did 10 years ago. I write less here at the Banter and show more pictures. Heck, I look at hundreds of images every day and post more than a handful regularly at my tumblr site (warning, it’s not generally safe for work). Through tumblr I’ve been hipped to hundreds of artists I wouldn’t otherwise know about. Thousands and thousands of pictures, man. It’s overwhelming but also beautiful.

Figure it’ll be fun to share some of the images, beyond the Art of the Day posts, with you. So: Picture this.

Photograph by Krisanne Johnson via MPD.

Pear by Caroline Dorcas Murdoch (19th Century)

It was a beautiful, crisp fall day in New York. The sun was out, the air was cool. Now, in the evening, it’s cold.

Good day for cooking. Made an apple crumble pie with The Wife this afternoon. We’ll have a slice each tonight, she’ll bring the rest to work tomorrow.

Meantime, after hours of football–and more tonight for the locals (Giants-Eagles, which is never no joke)–we’ve got Game 2 of the NLCS. The Giants cruised last night behind their stud, Bumgardner. Let’s see if the Cards can even the series before they head out to San Francisco.

Never mind nuthin’:

Let’s Go Yank-ees!

Picture by Bags.

Two games today. First, the AL, and tonight, Game 1 of the NLCS.

Let’s Go Base-ball!

Picture by Bags.

O’s vs. the Royals. It’s got a nice ring to it, doesn’t it? I’ll be happy for either team should they win but I’m siding with the O’s to start. Because of Buck, really. Plus, they’ve just got a lot of likable guys. Royals are hilarious, all those fast guys–Hosmer and Alex Gordon, and all those live arms in the bullpen.

Anyhow, hope it goes 7 and ends in extra innings.

Let’s Go Base-ball!

[Photo Via: Just in Weather]

Love him or hate him, Brian Cashman isn’t going anywhere. When he became the GM of the Yankees it was the most volatile position in pro sports. Now, he’s done what was previously unthinkable, and that’s survive.

[Photo Credit: Bruce Gilbert/Newsday]