The Yanks got pounded by the Orioles last night but it was hard to care after hearing the news that Robin Williams died.

From The Last Laugh By Phil Berger:

The idea that comic success did not equate strictly to laughs was a lesson [Larry] Brezner [the youngest partner in the Rollins/Joffe talent agency] had learned from Rollins several years before. “We were handling a comic in the 1970s who absolutely murdered an audience one night,” Brezner recalls. ” A standing ovation. Jack and I are walking over the party following the show. And I see a lock on Jack’s face. I say, ‘Jack, he got a standing ovation. You look disappointed.’ And he said: ‘Lad, it’s not what you do on the stage that counts, it’s what’s on the stage when you’ve left.’ Meaning, there are comics who make you laugh, and twenty-five minutes after, you’re left with nothing. Woody Allen didn’t give you huge laughs, but when he finished his last line, he’d taken on a persona over and above what he had done on stage.

“It was the most important thing Jack ever said to me. And a few years later with Robin, our ideas was he could be something better—that all he had to do is give himself a chance to do it. In those days, Robin had a character—and old man who’d feed the pigeons and talk about what had happened before World War III. He didn’t realize the potentially touching nature of the character. We convinced him at the end of his act to have the character say two or three funny things and then play the character for real. Told him not to worry if he gets laughs. Let the character talk about the foolishness of mankind. And then take the quiet moment walk offstage. We felt that after forty-five minutes of hysteria…do this and he’d elevate himself to an energetic freethinking comic, and one who could act as well….And I tell you, when he took the quiet moment and walked offstage without a laugh, the applause was deafening. You know, sitting in the audience, you’d just seen something special. He’d touched you. He left something on the stage for you.”

Robin Williams was one of my favorites when I was growing up. I remember him first as Mork. I saw Popeye in the theater when I was 9 years old then played the soundtrack album with my brother and sister until we wore it out. The World According to Garp was on heavy rotation on HBO not long after and I loved him in Moscow on the Hudson--which is still a favorite. His work in the PBS movie of Saul Bellow’s novella Seize the Day suggested he could go deep without the shtick.

Throughout the decade, I rooted for him to have a hit movie, which he eventually scored with Good Morning, Vietnam. Meanwhile, I memorized his second and third albums–Throbbing Python of Love (1983) and A Night at the Met (1986). They were such a part of the fabric of my teenage years I can’t even pinpoint a favorite routine–he was just always there.

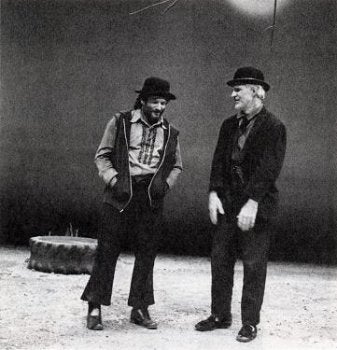

During my senior year of high school Williams was in a short-lived production of Waiting for Godot at Lincoln Center. Directed by Mike Nichols and co-starring Steve Martin, F. Murray Abraham, and the great Bill Irwin (who stole the show with a mesmerizing rendition of Lucky’s monologue), it was almost impossible to get a seat. Tickets weren’t sold to the public and Lincoln Center subscribers entered a lottery to get a chance to see the show. My high school French teacher happened to be one of those lucky subscribers–and she had an extra ticket. I told her I’d read the play in French–which I didn’t–and even though I’d dropped her course the previous semester, she took me.

I remember seeing Mary Tyler Moore and Mikhail Baryshnikov and Candice Bergen at the small Mitzi Newhouse theater. What the hell did I know but I thought the production was terrific, even though the critics panned it.

The following year, I had a job working as a messenger for a post production company in the Brill Building when Williams was in Awakenings with Robert De Niro. We transferred De Niro’s footage to videotape and when I wasn’t out on an errand I could sit in the machine room and watch. Penny Marshall, the film’s director, shot a ton of film, and although the movie is somber, Williams consistently broke De Niro up during takes.

I didn’t follow him as much in the Nineties after he became a huge movie star. Too many of his choices just seemed uninteresting, though he did have a few more moments left in him.

When I heard the news of his death today, I went to my bookshelf and pulled down a few Pauline Kael collections. Dig…

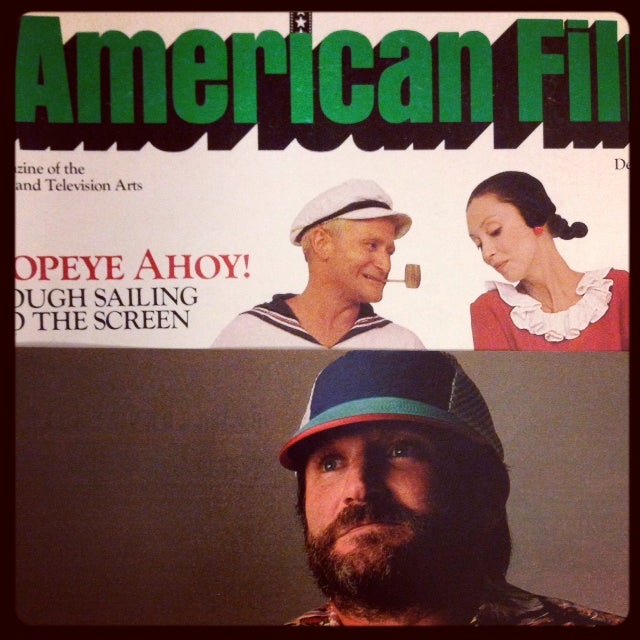

Popeye:

Robin Williams, who plays Popeye, has been given Popeye’s bulging forearms, and he has mastered the cartoon figure: the one-eyed squint that comes from talking with a corncob pipe in the mouth; the gruff, raspy voice; the personal patois, with “t” and “k” transposed; the shoulder-first swagger walk; the dancing acrobatics; the speedy round-the-world punch that requires winding up the wrist. He’s wonderful at all this mimicry. His cropped carrot-colored hair makes him look like a little kid, and his one blue eye is startlingly bright. He does prodigious work. But he never gets beyond the cartoon, never gives it anything of himself. And so he recedes, is swallowed up in the crowded background.

The Survivors:

The movie flits about, and there are spots where a viewer might nod off, but I enjoyed a surprising amount of it, and I think that Robin Williams’ work in it transcends the films’ flaws.

Williams plays Donald, a junior executive who gets fired on the same day that Matthau, as Sonny Paulso, the owner of a service station, loses his business. They meet at a lunch counter, where each man is trying to drown his sorrow in a cup of coffee. Being fired seems to have thrown a switch in Donald’s skull, wand when a masked holdup man (Jerry Reed) tries to rob the coffee shop he puts up such a squawk that Paluso goes to his aid, and together they disarm the bandit and, briefly, become media heroes. The whole experience of being fired and feeling helpless in front of the armed robber and getting on television turns Donald’s head. He becomes gun-crazy, buys an arsenal, and goes off for a course of training in survival tactics at a camp in New England; he wants to learn how to be violent, so he can live in the wild and protect himself when the social order collapses. The comedy is in the contrasting natures of Donald and Paluso. Everything surprises Donald. He’s a sweet-natured hysteric who over responds to every stimulus. He has the nervous system of an infant; the transitions between mood changes aren’t visible—he doesn’t consider, he reacts. Paluso is the opposite. Nothing surprises him; he gives the impression of having learned all there is to know about survival (in the big city) long ago. He’s cautious and jaundiced, with the kind of cynicism that used to be ascribed to Manhattan cabbies. And when the would-be-robber (a sociopath with delusions of being a big-time hit man and of having killed Jimmy Hoffa) is released from custody and goes after the two men, Paluso tries to get Donald to behave rationally—i.e., cravenly—so they won’t both be killed.

The best thing about this framework is that it permits Robin Williams to be himself and yet to be Donald. He acts with an emotional purity that I can’t pretend to understand. Williams expostulates all through the movie; he sputters out his short-circuited thoughts. He seems to be free-associating twenty-four hours a day; you know that his mind is racing even when he sleeps. And this spritzing never seems false or prepared. He spritzes in character. It’s like a child’s stream-of-consciousness: you see him making mad comparisons and landing from mental leaps, but you never see him take off. A lot of the comedy comes from him being a grownup with this ranting little kid inside him…He uses his hairy, broad-chested, no-neck body for the naked “universal” emotions that mimes strive for, and he achieves them (in a speeded-up form) without attaching big labels to them. He may be that rarity, a fearless actor.

Moscow on the Hudson:

Mazursky’s instinct was really working for him when he paired Robins Williams with Maria Conchita Alonso, a Venezuelan beauty who’s an unself-conscious cutup, like the young Sophia Loren, and has a glorious, full-choppered grin. Her Lucia is outgoing, independent, shunshiny; she has come to this country to make something of herself—she would like to be a newscaster. Robin Williams’ Vlad is an anonymous Soviet man hoping for the creature comforts of a home and a family—a supplicant always. The bathtub scene, in which Lucia leans back against his furry chest while his furry arms enclose her, is physical in a way that disposes of the steam-house contortions of the lovers in Against All Odds. These two suggest real people.

Club Paradise:

As the club’s social director, Robin Williams is the picture’s m.c., and his role is largely reactive. He doesn’t have a chance to do the kind of acting he did in The Best of Times or Moscow on the Hudson, but it’s surprisingly enjoyable to see him when he isn’t charged up. He gives the movie a sane, low-key center. His lines are mostly asides or are given the sound of asides, and he’s congenial—he has a graceful style that he adapts to each of his several partners. In the early sequences, he persuades Twiggy to leave the yachting party she arrived with and stay with him, and he does it without coming on strong. That’s why she’s attracted to him; he’s honest and, in some unfathomable way, winning. Twiggy doesn’t have running gags or terrific lines, but she does radiant double takes on Robin Williams’ good lines—she’s charming. In Williams’ friendship and business partnership with Jimmy Cliff, it’s taken for granted that we’ll perceive what makes them trust each other, and we do. Perhaps most surprising is Williams’ nifty teamwork with Peter O’Toole, who plays the governor-general of this flyspeck British island. When Robin Williams and the dulcet-voiced, eloquent O’Toole talk together, their two styles of acting mesh almost conspiratorially.

Good Morning, Vietnam:

The only fresh element in American movies in the eighties may be what Steve Martin, Bill Murray, Bette Midler, Richard Pryor, Robin Williams, and other comedians have brought to them. They’ve stirred things up even when they’ve been in squalid excuses for movies (such as Martin’s current hit, Planes, Trains and Automobiles). The one with the best record is Robin Williams…he hasn’t had many hits, but his films weren’t smarm—not until now. His new picture, Good Morning, Vietnam, makes him out to be a vulnerable, compassionate, respectful-of-the-Vietnamese, wonderful guy, and the director, Barry Levinson, has a numbing sense of rhythm: he labors the jokes.

…The role makes it possible for Williams to do his own manic riffs, but they’re chopped shorts—they don’t get a chance to build. And we might as well be listening to a laugh track; we’re told Adrian is funny, instead of being allowed to discover it….This movie has the bad judgment to turn Robin Williams into a role model. Good Morning, Vietnam takes a real culture hero and turns him into a false one.

Dead Poets Society:

Robin Williams’ performance is more graceful than anything he’s done before. He’s more restrained, yet he’s brisk, enlivening, a perky, wiry fellow.

Williams stays in character, but he understands that a teacher who wakes kids up is likely to be a standup performer, maybe even a comic, and certainly quick on his feet. Williams reads his lines stunningly (he’s playing a bright man), and when he mimics various actors reciting Shakespeare there’s no undue clowning in it; he’s a gifted teacher demonstrating his skills. That’s what he’s doing when he hops around the classroom and makes the kids laugh.

Awakenings:

This is another one of Robin Williams’ benevolent-eunuch roles. He’s the good man here, as he was in Good Morning, Vietnam and Dead Poets Society, and he does a fine job of it: he shows warmth and reticence and empathy that Dr. Sayer needs. Sayer needs something else, though, in order to be a real character: some ruthlessness, perhaps, or more egotism—something to keep him from being a noble fud. And Williams shouldn’t have to hold himself in like this. He’d better move on, before he turns into the movies’ permanent winsome messiah.

And from a 1992 interview in the Oxford-American with Marc Smirnoff:

I love what Robin Williams did in The Fisher King which came out after the period I reviewed in [Movie Love]. Have you seen it? The acting in it is really extraordinary…Williams may be playing the holy fool, which he’s played before and which I found tiresome in Awakenings, but in the Fisher King I thought he was really great.

I had the Yankee game on when my friend Alan called to commiserate. In the top of the second the Yankees scored a couple of runs on a play where the Orioles committed two errors and looked like something spun out of a Mack Sennett production. All that was missing was a pie in the face and a bottle of seltzer. For that moment we stopped being sad and thought of Robin Williams and laughed.

[Featured image by Annie Leibovitz]

Nice tribute, Alex. Man, did Kael have him pegged as an actor.

Dead Poets is my favorite Robin Williams movie and performance.

I'll remember Williams as the funny guy who was always there, and always on.

He was always on the talk shows doing his thing, and making you laugh, or at least smile for a few minutes. I liked to think of him as a funny mensch, whose gears were always turning. Of course it was all an act, but a damn good one, for a long time.

My favorite memory was the cameo he made in a 60 Minutes interview with Jonathan Winters (who played Mork's son - remember they aged in reverse on Ork.)

Winters was a hero of Williams'. So Williams barges in on ( I think it was) Ed Bradley's interview with Winters, and hijacks the scene. A completely contrived stunt, but one that made you laugh and smile, as Robin Williams always did.

It's profoundly sad to think of a guy as talented and likable as Williams being tortured and pushed over the edge by his inner demons. He will be deeply missed.

Sad. Robin Williams left us with so many great memories - memories that take us back to a previous time, where we remember our laughter and the joy we were experiencing so fondly and so vividly.

He was apparently a sweet guy, too.

Here's that 60 Minutes segment with Williams and Winters (Robin enters a few minutes in)

http://www.youtube.com/watch?v=iDJjq0Pd0RM

4) Thanks for that.

Last night was such a difficult time for me. Many celebrities pass away, and as I get older, many of the heroes of my youth will pass on. This was the toughest by far, and his suicide makes the pain even worse.

We were having a dinner party with 2 friends, and I just couldn't bring myself up to it. The idea that this man that I loved, who I never knew, but for his art made my head spin.

I say grace with our family before dinner and we talk about what we are grateful for. Last night, we had an abbreviated grace and I said, "Let's pray for Robin Williams." Our 2 friends and my wife apparently hadn't heard the news, and thankfully with the kids at the table, we could quickly move on, and not dwell on it.

Later that night after putting the kids to bed, I was dwelling on it, and felt this sadness that is usually reserved for the loss of a family member or dear friend.

It will be hard to watch his movies and divorce the man from the character he portrayed, but I will now have more of an appreciation for the joy he bestowed on others in the face of his own unfathomable pain.

Thanks for sharing Alex! I love you pal!

Love you too, G. And I felt similar to you about him. And since I haven't watched many of his movies of the past 15 years it sort of caught me by surprise.