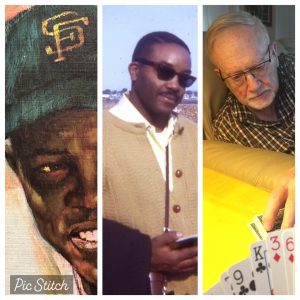

Two great men who were born within weeks of each other in 1931 passed away recently. The one you know is Willie Howard Mays, Jr., one of the greatest players who ever lived.

We’ve been measuring baseball players for a hundred and fifty years, first counting the things we could see, like balls hit over a fence or the number of times a fly ball was picked out of the sky, then eventually with mathematical equations that would’ve made Babe Ruth shrug and then slug another beer.

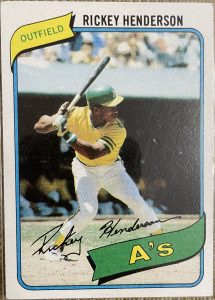

By any measurement you care to use, Willie Mays was elite. If the folks in Cooperstown ever decide to create an inner circle, a Hall of Fame Hall of Fame, Mays will be a first ballot selection. With 660 home runs, twelve consecutive Gold Glove awards, and 24 All-Star selections, this kid from Alabama by way of the Negro Leagues was more than just great. He did things on the field in the 1950s and ‘60s that no one had ever seen, at least not in the white major leagues.

But nothing on the back of his baseball card can begin to define Mr. Mays. He is among that handful of players who seems more mythology than history, but with Mays the stories are generally true. He really did stop to play stick ball in the streets of New York as he walked home from the Polo Grounds. He really did run out from underneath his hat each time he rounded second. (Never mind the fact that he wore that hat a size or two large to be sure it happened that way.) Even his nickname, “the Say Hey Kid,” was better than everyone else’s.

Mays was only three years into his career, just 23 years old, when he produced arguably the most famous play in baseball history. In the eighth inning of Game 1 of the 1954 World Series, Cleveland’s Vic Wertz launched a rocket over Mays’s head, a ball sure to find the depths of the Polo Grounds’ cavernous center field. Many have said that it wasn’t Mays’s greatest catch, but it happened on the game’s greatest stage, so that was enough.

With the 24 on his back facing the plate, Mays outran the ball, the ball fell into his glove, and America fell in love with Willie Mays. The iconic play was captured in Arnold Hano’s seminal book A Day in the Bleachers, a fan’s eye account of that entire game. When I spoke with Hano about that play as part of a larger interview, the writer explained it simply. “He outran the ball, I mean that’s what it amounted to. In fact, I write in the book that he started to look over his shoulder and then thought better of it. I think what he did, he probably had great peripheral vision. He probably looked over his shoulder just to make sure the ball was where it should be. I think that’s what happened, now that I think back on it.”

Now that I think back on it — and it says something else about Willie Mays that I can think back on a play that happened fifteen years before I was born and remember it as if I had been there — I see Mays racing back and making the catch, but before anyone can appreciate what he’s just done, he’s already spun back around like an Olympic discus thrower and fired the ball back towards the infield, finishing the play on his hands and knees, his hat lost somewhere behind him.

Mays was in the first wave of Black ballplayers raised in the Negro League era to become superstars in the white major leagues. Though he arrived four years after Jackie Robinson, his journey was no less fraught. He was already one of the most famous men in America when his New York Giants moved to San Francisco in 1958, but in the eyes of many he was just a boy. He fit in New York City, but when he and his wife drove their Cadillac into the nicer neighborhoods as they searched for a home in San Francisco, they were met with resistance. They were met with reality.

When Black baseball fans across America looked at Mays, they saw not just a hero of mythical proportions, they also saw themselves. They might not have been able to smash a ball into the seats or glide effortlessly into the gap to watch a triple die in their gloves, but they knew the same discriminations and indignities that he knew.

Maybe that was why my father was drawn to him. In the late spring of 1969, my Black father and white mother drove from their home in Detroit for a vacation out west. They’d been married less than a year, they had a child on the way, and all was good in their world.

They travelled up the coast to San Francisco, and they saw all the sites. They walked along Fisherman’s Wharf, they rode the street cars, and they went to Candlestick Park to see Willie Mays. Growing up in an American League city long before interleague play, this would’ve been my father’s first and only chance to see Mays. Going to San Francisco without stopping for the Say Hey Kid would be like visiting the Louvre and skipping the Mona Lisa.

Somewhere on a hard drive I’ve got the scan of a picture my father took that night. The photo is blurry, but it shows a right-handed batter in a Giants uniform, so it can only be Mays. Not as blurry is the image I imagine on the other end of the camera. My father is looking at a legend, my mother is sitting beside him, and I am the dream that floats between them.

Less than a week later, my father had a heart attack and died during the night in a motel room in Seattle. His last baseball game was my first, and even though I wouldn’t come into the world for another five months, I like to believe that my love of the game began that night in San Francisco.

Four years later, in October of 1973, my mother remarried. His name was Frank, but he was always Dad to me. My father had passed away before I was born, but my dad raised me to be the man I am today.

When a friend texted me on April 27th to tell me that Willie Mays had gone into hospice, I got the news while sitting alone in the Oakland airport just six hours after my dad had died, his own hospice journey having ended that morning. As I sat there waiting to board my flight home, a circle closed.

In 1972 the 41-year-old Willie Mays was traded from the Giants to the Mets, allowing the legend to return to the city where he had first become a star, but he was far from the player New York fans remembered. That final season and a half was notable only because it gave reporters a reference point any time any aging star reached the end of their career. Even fifty years later it isn’t unusual to read that trite admonition: “You don’t want to go out like Willie Mays, dropping fly balls in Shea Stadium.”

It always seemed such a self-centered observation, as if the decline of a legend had anything to do with the player he once had been. Wasn’t it more admirable to hang on to the game you loved? Wasn’t there something beautiful in a desperate devotion to linger years after many thought your time had passed? If Mays wanted to keep playing, let him. I simply couldn’t understand why anyone might have thought otherwise.

And then my dad fell into the cold grip of Alzheimer’s, and suddenly it all made sense. Intellectually, he had always been Willie Mays, but then one day he began dropping fly balls.

Quite simply, he was the smartest man I’ve ever known. At about the time Willie was travelling from Alabama to New York, my dad was taking a train from Pennsylvania to Cal Tech, sharing a berth with a young actor named Leonard Nimoy who was on his way to the Pasadena Playhouse. (But when my dad told the story, it was always Lenny Nimoy, which somehow made it better.)

After Cal Tech he went on to earn a PhD from Case Western Reserve and embark on a long career as a chemist. As I was growing up, there was no question he couldn’t answer and nothing he couldn’t fix. One of my biggest regrets is that with all the hours I spent as a child “holding the light” as he worked deep into the night on one repair or another, I never bothered to pay attention. I still can’t fix a damn thing.

I still remember the cruel realization that my dad had slipped away. It was probably ten years ago, and there was something scientific that was bothering me. It might’ve been a question about how long it took my cell phone battery to charge or something similar, but when I picked up my phone to call him and ask, I put it back down before dialing. He wouldn’t know any more. He had been dropping fly balls for a while at that point, forgetting even the most important people in his life. The last time my family and I visited, he didn’t know us. We were just five nice people who stayed for a while and gave him a hug when we left. I cried as we pulled out of the driveway and headed home, not because he was dead but because he wasn’t. He was already gone.

When it was clear last month that his final days had arrived, I wasn’t sure that I wanted to see him. But when my mom told me he had only another 48 hours or so, I got on a plane.

He hadn’t been conscious for a while, but my mom and I sat with him during those final days and hours, as much for each other as for him. She asked me what my favorite memory was, and several came back immediately.

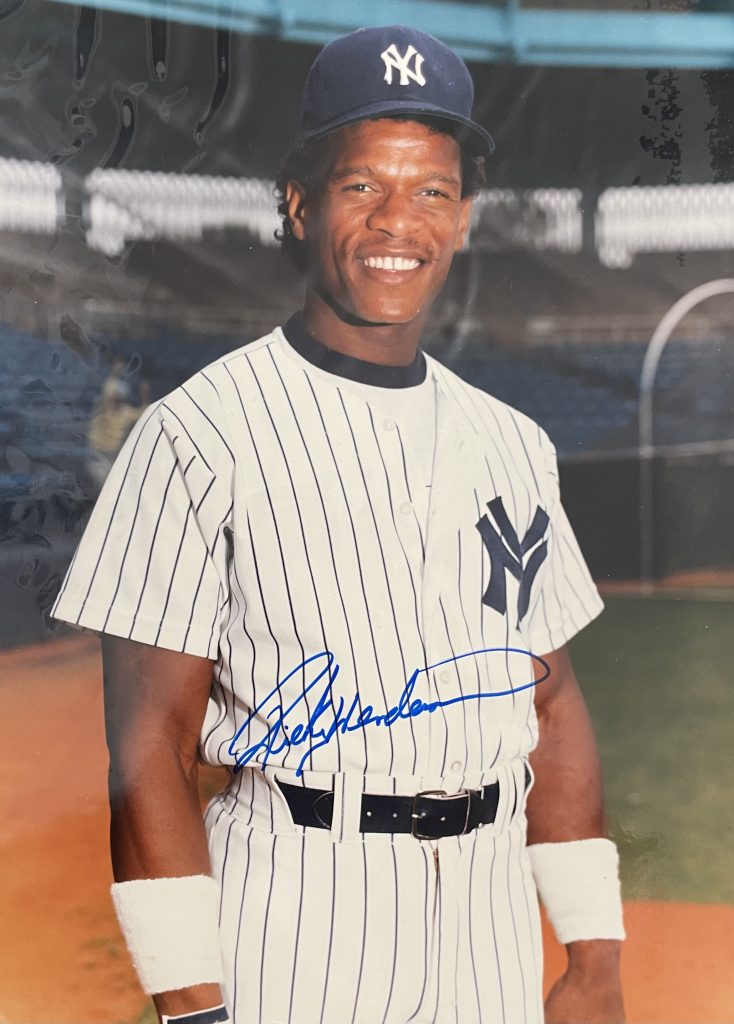

There were general memories, like the dozens of baseball games he took me to, including the game at Yankee Stadium when I was seven, the game that made me a Yankee fan for life, but there were others. We entered the Pinewood Derby when I was six or seven, and it wasn’t even fair. The other dads dutifully carved their block of pine into something that resembled a car and slapped on some paint, but our car was serious. My dad bored two holes in the bottom and filled them with solder for extra weight, then took apart the wheel casing and dusted the axles with graphite to reduce friction. There were hundreds of other competitors, but they didn’t stand a chance. I’ve still got the car and the 1st place trophy it earned packed away in the garage.

When I once told him that I had waited until the last minute to do my science project, he didn’t blink. He went to the garage for some supplies and together we built an electromagnet. Years later I’d guide my daughter through the same project.

He had always been a better dad to me than I a son to him, and one way he showed his love was by constantly looking for opportunities to spend time with me doing something that I loved. My favorite memory came when I was much older, during a time when I was pulling and away and was trying to keep my close. While I was home during a break from college, he suggested we go to the driving range. It had probably been forty years since he had swung a golf club, but since I had been playing fairly regularly, he knew it would be something we could do together. We got a bucket of balls and took two spots on the range. He teed up with his back to me, took a mighty swing, and completely missed the ball. He pivoted a hundred and eighty degrees as the momentum of his swing spun him around so he was facing me, and I’ll never forget what came next. He laughed with a huge smile on his face, and while it might’ve been triggered by embarrassment, it quickly dissolved into pure joy, the joy that can only come from time spent with your son.

These two men, my father and my dad, somehow linked by Willie Mays, made me who I am. Nothing makes me happier than when my mother or someone who knew my father points out a physical similarity that’s been passed down through our shared DNA, but I’m old enough now to admit there’s a lot of my dad in me also.

When we’re driving somewhere and my wife asks me why I’m taking a strange route to a familiar place, I know it’s because of my dad. When I carry my shoes to the car and tie them at the stop lights, I know it’s because of my dad. When I tell a story that takes longer to get to the point than my listener might like, I know it’s because of my dad.

But when I sit with my son in Yankee Stadium this week, I know it will be because of both of them. I’ll think about my father making a pilgrimage to see Willie Mays, I’ll think about my dad playing catch with me in the front yard, and even though I’ll try not to, I’ll think about my son and the games he’ll watch without me after I’m gone.

Oh-ho! Haven’t seen this for a while now, have you? However, this time it’s ol’ Chyll Will taking a ride up the kitchen isle in order to share a neat recipe that he sort-of made up while doing a little R&D in his apartment kitchen. So, while we wait for the team to start up a new series in Arizona, why don’t I give some serious consideration to an experiment gone right with some

Oh-ho! Haven’t seen this for a while now, have you? However, this time it’s ol’ Chyll Will taking a ride up the kitchen isle in order to share a neat recipe that he sort-of made up while doing a little R&D in his apartment kitchen. So, while we wait for the team to start up a new series in Arizona, why don’t I give some serious consideration to an experiment gone right with some