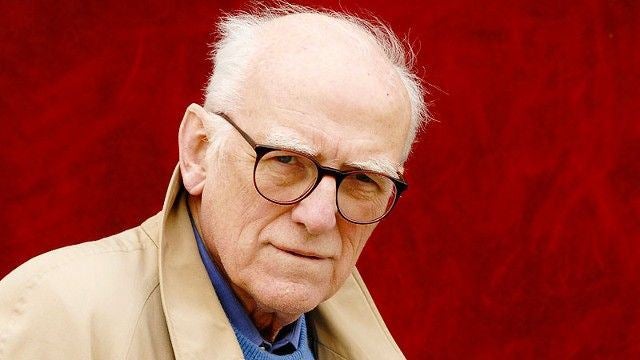

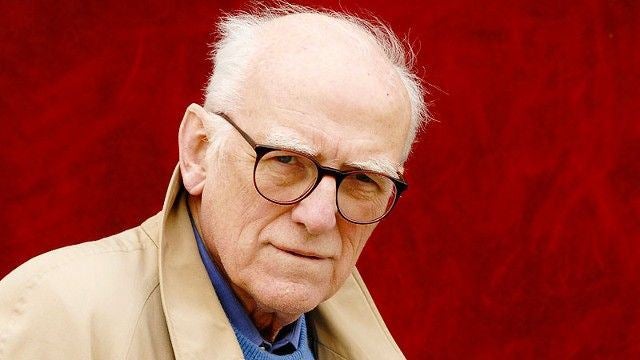

Donald E. Westlake (1933-2008) was one of our most prolific and entertaining writers. Now, we’ve got this posthumous treat: The Getaway Car: A Donald Westlake Nonfiction Miscellany, published by the University of Chicago Press and edited by Levi Stahl. The book is a ton of fun. I recently had the chance to catch up with Stahl. Hope you enjoy our chat.

Q: When did you start reading Donald Westlake?

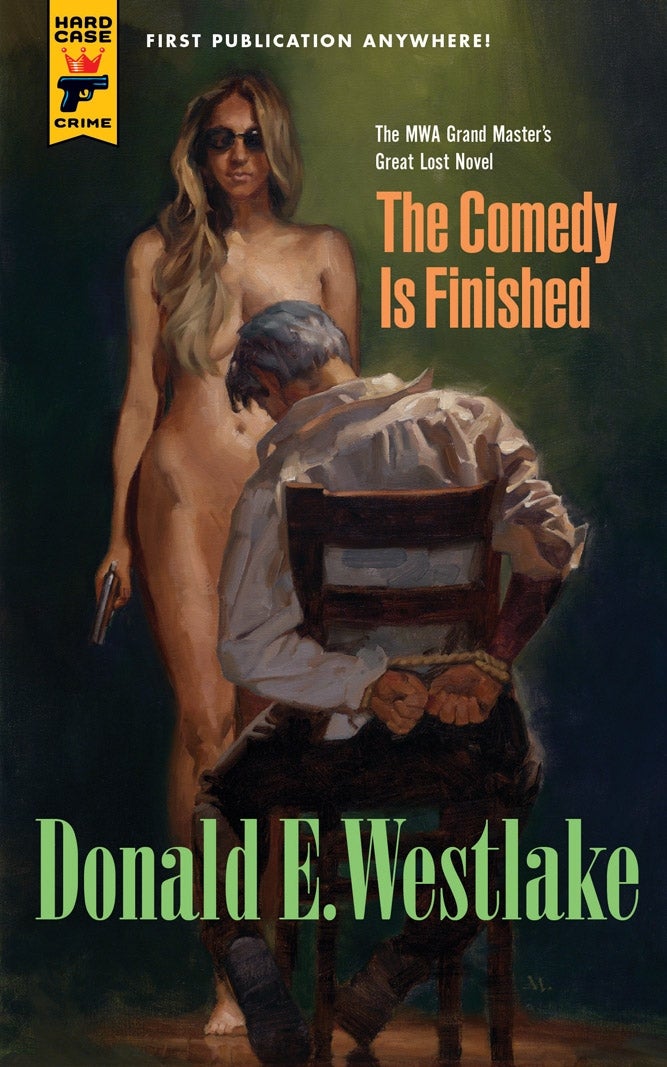

Levi Stahl: I first encountered Westlake via Hard Case Crime: they published Lemons Never Lie, one of the novels he wrote under the name Richard Stark about the heister Parker’s associate Alan Grofield. I was impressed by it, but in that way that happens when you read a lot, I just kept moving and didn’t dig deeper.

Then on the day before Thanksgiving in 2007 I was at the office—and if you’ve ever been in the office the day before Thanksgiving (and don’t work for Butterball), you know that absolutely nothing happens. You’re there just in case something catches fire. That day, nothing was even smoldering, so at lunch I went browsing at my local bookshop, 57th Street Books, and plucked from the shelves what would end up being the penultimate Parker novel, Ask the Parrot. Back at my desk, I set to reading, and two hours later when my wife arrived for the long drive downstate to my parents’ house, I had to apologize: I had promised to do the driving, but now there was no way I could do any driving until I’d finished this book and found out what happened.

I was hooked. By Christmas I’d read ten or so Parker novels, all harvested from the used book market, and was making the case to colleagues at the University of Chicago Press that we should try to bring the series back into print. Now, almost seven years later, I’ve read all 100 of Westlake’s books—the Westlakes, the Starks, the Samuel Holts, the Tucker Coes, and the one-shots from Timothy Culver, Judson Jack Carmichael, Curt Clark, and even “The Vibrant J. Morgan Cunningham.” And almost all have been worth reading—even the couple that I would regard as truly weak offer some elements of interest.

Q: Damn, Westlake wrote 100 books? And you read them all? Man, that’s daunting. Okay, before we even get to the collection you’ve assembled, what Westlake titles would you recommend for someone who’s never read him before?

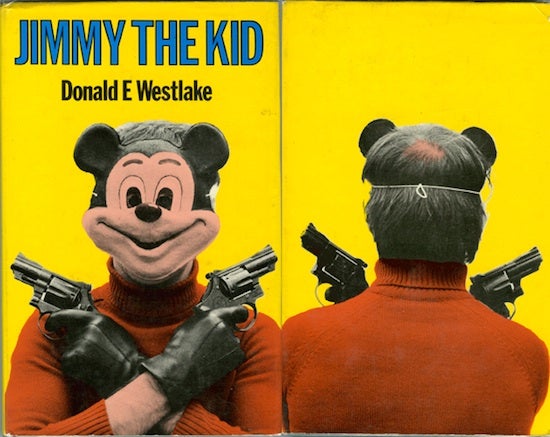

LS: The two series are an obvious starting point: trythe first Parker book, The Hunter, and the first Dortmunder, The Hot Rock. Neither is necessarily the best in the series, but they’re both quite good, and they give a clear sense of what these books are up to and whether you’ll like them.

From the standalones, I tend to recommend Somebody Owes Me Money, a hilarious first-person narrative from a put-upon cabby that opens, “I bet none of it would have happened if I wasn’t so eloquent”; Killing Time, an early, hardboiled work that is clearly in thrall to Hammett and Red Harvest but satisfying on its own terms; 361, a crime novel that was written deliberately with no explicit emotional signposts; God Save the Mark, a brilliantly funny collection of cons and nonsense; and The Ax, a 1997 hardboiled crime novel that is also a dissection of contemporary economic pain, as a laid-off print shop manager decides to kill the competition for the job he’d like to land. It’s so unrelenting it can be hard to read at times.

Q: Also, for the uninitiated, can you talk about the difference between Westlake’s two most famous protagonists?

LS: What may be more interesting about Parker and John Dortmunder is a relatively underappreciated quality that they have in common: they’re both extremely good at their jobs, yet their well-laid plans always go spectacularly wrong. The difference comes in how they respond to that. Parker, while remaining utterly emotionless, is bothered when a job goes sour, and he then takes whatever measures are necessary, up to and including extreme violence, to extricate himself from the problem, preferably with the loot. Dortmunder reacts to problems with an unsurprised shrug of his shoulders. Everything has always gone wrong for him, so why should this time be any different? Parker is an existentialist, Dortmunder is a fatalist.

Dortmunder actually emerged out of those very differences: Westlake started writing what he thought was another Parker novel, in which Parker and a gang have to try multiple times to steal a giant diamond. When he got to the third or fourth time the gang tried to steal the diamond, however, he realized he couldn’t keep going: Parker would have already cut his losses and moved on. But he liked the concept enough that he created a heister who would just keep plugging away at it, and with that, The Hot Rock started really rolling, and John Dortmunder was born.

The other big difference is that Dortmunder actually likes and cares about his gang. They’re almost as much friends as colleagues, and it shows in his willingness to continue to put up with their irritating, silly quirks. Parker, on the other hand, sees his colleagues as mere tools, useful yet, like all tools, prone to failure. So the one time he does truly extend himself for a fellow heister—risking his life, and the job, to save Alan Grofield in Butcher’s Moon, it astonishes not just the other guys on the string, but the reader, too. The Parker novels are popcorn, or shots of whiskey; the Dortmunders are chicken soup, or a PB&J. You go to them on different days, for different reasons, and they deliver what you’re looking for.

Q: Okay, to the collection that you’ve edited. How did this project come about?

LS: I discovered Westlake the nonfiction writer via Trent Reynolds’s excellent Violent World of Parker site. He had posted a scan of an Armchair Detective article from the early 1980s that reproduced a talk Westlake had delivered at the Smithsonian about the history of hardboiled private eyes in fiction. That piece revealed Westlake to be a serious thinker about and critic of the crime genre, and it made me wonder what else he might have written. Quick searching turned up enough to build a book proposal, deeper library research fleshed it out nicely, and—best of all—a trip to the Westlake house to go through his files, courtesy of the endlessly gracious Abby Westlake, turned up a bounty of little-known and never-before-published pieces.

Q: With a guy as prolific as Westlake, how did you decide what to choose from—not only single pieces—but categories?

LS: The categories actually came last, when I looked at my giant stack of papers and realized, belatedly, that I would need to put them in some sort of sensible order. But once I started doing that, making stacks of pieces on Westlake’s own work, of pieces on other writers, of letters, etc., the very act of sorting helped me figure out whether I wanted to include the couple of pieces that were on the bubble. For example: you could probably do a whole book of Westlake interviews, but once I gathered what I had, it became obvious that the two I should include were the ones that focused largely on his film writing career, as most of the other topics that come up in interviews (his life and his books) were covered elsewhere.

My early readers, Charles Ardai of Hard Case Crime and Sarah Weinman, editor of Troubled Daughters, Twisted Wives, were also extremely helpful: seeing what pieces interested these two genre experts most, and which were less effective, helped to transform the early manuscript into something more compact and potent. The only piece that I knew from the very start had to be in the place it is was the final letter. The moment I read it, pulled from Westlake’s filing cabinet, I knew I had the last words of the book.

Q: Westlake’s generosity toward his peers—Rex Stout, Charles Willeford, even a review of a George Higgins novel come to mind—is admirable. He seemed not motivated by professional envy but professional admiration. I like the note he tacked up at his desk, NO MORE INTRODUCTIONS, but the truth is, he was very good at writing them, wasn’t he?

LS: He really was an astute and generous critic of other writers. His essay on Peter Rabe, whom he greatly admired and acknowledged was a huge influence, is the perfect example. In the book that section opens with a letter from Westlake to Rabe telling him he’s going to be writing about his work and asking some questions; the letter is appreciative, funny, and generous, and Rabe responded enthusiastically. However, knowing that Rabe would eventually read the essay clearly didn’t stop Westlake from offering strong criticism of his weaker books—but at the same time, the admiration for Rabe’s achievement is so strong, clear, and well grounded in detailed analysis that the overall effect is to make you come away wanting to read more of Rabe’s books. Ultimately, that’s the effect of all of Westlake’s introductions: it’s the job of the person writing the introduction to make you see what’s special about the writer being presented, and Westlake was spectacularly good at that.

Another example of his ability to analyze and offer criticism of crime fiction is the letter to David Ramus. Ramus had—I’m not sure through what channel—sent Westlake the manuscript of what would become his first novel, On Ice. I don’t know what he was expecting, but what he got was a detailed examination of what did and didn’t work in the book, with suggestions of how things could be done better—suggestions given, explicitly, not to say that Westlake’s way was right, but that another way was possible. The letter, and the investment of time it represents, is an act of stunning generosity. The most entertaining moment in that letter? “Finally, I have one absolute objection. We do not overhear plot points. No no no.”

Q: Can you describe how he used humor in his books? His wife said he wasn’t jolly in real life, but witty, loved to laugh and loved making people laugh.

LS: In his foreword to this book, Westlake’s friend Lawrence Block takes issue with my characterizing Westlake’s writing as being filled with jokes. It’s wit, rather than jokes, says Block, and I think he’s basically right. Perhaps the biggest thing I took away from my time researching this book was that Westlake hardly ever wrote a full page of anything—be it fiction or a business letter—without finding a way to get some humor into it. He just seems to have seen the world that way: everything is a tiny bit ridiculous, because, well, look at us? We’re not really very good at this living stuff, are we? Yet we have the audacity to make plans and think we’re in control. That illusion is the source of so much of Westlake’s humor. Everything is always going wrong, and that in and of itself is funny, if you look at it the right way. As he put it in his piece on Stephen Frears, “If we aren’t going to enjoy ourselves, why do it?” He really seems to have written, and lived, with that motto in mind.

Q: The most delightful surprise in the book is the chapter on the Goon Show, the British radio comedy hit that was the precursor to the Pythons and Beyond the Fringe.

LS: Wasn’t that unexpected? Westlake was a comic writer, obviously, but like you I was still surprised to find him writing about the show, and weaving his appreciation of it into a short autobiographical essay. I’d thought a lot about his genre forebears and influences, but I’d never given the same thought to the influences on his comedy.

Q: What did you find that surprised you?

LS: For me the biggest surprise was more structural: I knew that Westlake had written for Hollywood, but it wasn’t until I was going through his files that I realized what a big part of his work, and income, it was. Even as he was writing 100 books, he was also turning out screenplays, and treatments, and pilots, and rewrites, most of which never made it to the screen. That was a big reason why I wanted to include the two interviews that focused on film, and the piece on Stephen Frears: it’s a side of Westlake that I think even those of us who are big fans don’t necessarily know about. (My only regret with the book, meanwhile, is that I couldn’t find a way to work in even a single reference to Supertrain!)

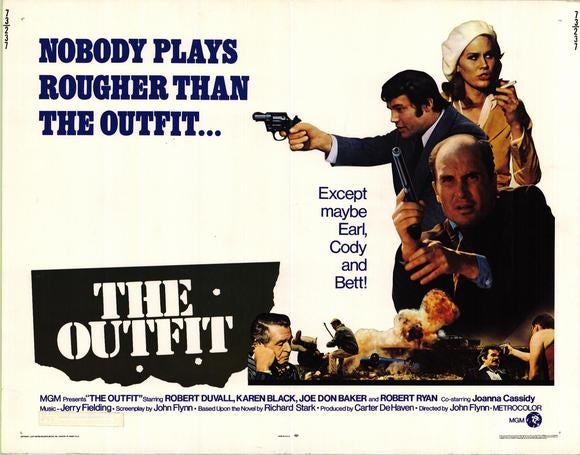

Q: What were Westlake’s experiences with Hollywood like? Several of his books were made into movies, some of them good—The Hot Rock, Point Blank. I didn’t know it at the time but I first remember seeing his name in the credits for The Grifters and a very good, creepy movie, The Stepfather.

LS: He worked hard with Hollywood and drew a substantial part of his income from there throughout his life. But he always seems to have held it at arm’s length. You get the feeling that the loss of control and independence that working with Hollywood, even in the relatively isolated role of screenwriter, required sat awkwardly with Westlake’s lifelong iconoclastic, individualistic, rebellious streak. There’s a reason that he didn’t like, and didn’t stick in, the Air Force; that same reason seems likely to be why Hollywood never truly seduced him.

Q: In a letter, Westlake described the difference between an author and a writer. A writer was a hack, a professional. There’s something appealing and unpretentious about this but does it take on a romance of its own? I’m not saying he was being a phony but do you think that difference between a writer and an author is that great?

LS: I suspect that it’s not, and that to some extent even Westlake himself would have disagreed with his younger self by the end of his life. I think the key distinction for him, before which all others pale, was what your goal was: Were you sitting down every day to make a living with your pen? Or were you, as he put it ironically in a letter to a friend who was creating an MFA program, “enhanc[ing] your leisure hours by refining the uniqueness of your storytelling talents”? If the former, you’re a writer, full stop. If the latter, then you probably have different goals from Westlake and his fellow hacks.

But does a true hack veer off course regularly to try something new? Does a hack limit himself to only writing about his meal ticket (John Dortmunder) every three books, max, in order not to burn him out? Does a hack, as Westlake put it in a late letter to his friend and former agent Henry Morrison, “follow what interests [him],” to the likely detriment of his career? Westlake was always a commercial writer, but at the same time, he never let commerce define him. Craft defined him, and while craft can be employed in the service of something a writer doesn’t care about at all, it is much easier to call up and deploy effectively if the work it’s being applied to has also engaged something deeper in the writer. You don’t write a hundred books with almost no lousy sentences if you’re truly a hack.

Q: I loved the piece that Westlake’s wife wrote about his working habits.

LS: Isn’t it great? In her tongue-in-cheek, yet insightful essay “Living with a Mystery Writer,” Abby Adams Westlake talks about the differences she would see in her late husband depending on which of his many personas he was writing as. In discussing his Timothy J. Culver pen name, she describes his writing set-up:

“His desk is as organized as a professional carpenter’s workshop. No matter where it is, it must be set up according to the same unbending pattern. Two typewriters (Smith Corona Silent-Super manual) sit on the desk with a lamp and a telephone and a radio, and a number of black ball-point pens for corrections (seldom needed!). On a shelf just above the desk, five manuscript boxes hold three kinds of paper (white bond first sheets, white second sheets and yellow work sheets) plus originals and carbon of whatever he’s currently working on. (Frequently one of these boxes also holds a sleeping cat.) Also on this shelf are reference books (Thesaurus, Bartlett’s, 1000 Names for Baby, etc.) and cups containing small necessities such as tape, rubber bands (I don’t know what he uses them for) and paper clips. Above this shelf is a bulletin board displaying various things that Timothy Culver likes to look at when he’s trying to think of the next sentence. Currently, among others, there are: a newspaper photo showing Nelson Rockefeller giving someone the finger; two post cards from the Louvre, one obscene; a photo of me in our garden in Hope, New Jersey; a Christmas card from his Los Angeles divorce attorney showing himself and his wife in their Bicentennial costumes; and a small hand-lettered sign that says ‘weird villain.’ This last is an invariable part of his desk bulletin board: ‘weird’ and ‘villain’ are the two words he most frequently misspells. There used to be a third—’liaison’—but since I taught him how to pronounce it (not lay-ee-son but lee-ay-son) he no longer has trouble with it.”

In an interview conducted by Albert Nussbaum, Westlake went into a bit more detail about his approach:

“If I work every day from the beginning of a book till the end, my production rate is probably three to five thousand words a day–unless I hit a snag, which can throw me off for a week or two. But if I work every day I don’t do anything else, because everything else involves alcohol; and I don’t try to work with any drink in me, so in the last few years I’ve tended to work four or five days a week. But that louses up the production two ways; first in the days I don’t work, and second, because I do almost nothing the first day back on the job. This week, for instance, I did one or two pages monday, five pages Tuesday, five Wednesday, fourteen Thursday, and three so far today.” He went on to say that he used to complain to his second wife, “I’m sick of working one day in a row!”

Q: Craft was central for Westlake. In some ways, his Parker books are an appreciation of craftsmanship, aren’t they?

LS: When I first started reading the Parker books, what struck me was that they were essentially books about work. In the first one I read, Ask the Parrot, Parker sets up a hidey-hole in an empty house, carefully sawing off some screws in the wood that’s boarding it up so that he can get in and out easily without being detected. The activity is described in detail, and I’m pretty sure Parker doesn’t ever end up needing the hideout. But it was part of doing the job (in this case, the job of staying alive after a failed heist), so Westlake included it. (I wrote a bit about the Parker novels as books about work on my blog way back in December of 2007.)

Luc Sante, in his foreword for some of Chicago’s Parker editions, put the same point this way:

“Westlake has said that he meant the books to be about ‘a workman at work,’ which they are, and that is why the have so few useful parallels, why they are virtually a genre unto themselves. Process and mechanics and troubleshooting dominate the books, determine their plots, underlie their aesthetics and their moral structure. . . . Parker abhors waste, sloth, frivolity, inconstancy, double-dealing, and reckless endangerment as much as any Puritan. He hates dishonesty with a passion, although you and he may differ on its terms. He is a craftsman who takes pride in his work.”

There’s a passing line in The Man with the Getaway Face that has stayed in my head for seven years now: “When the mechanic came in at seven o’clock, he looked at the truck in disgust. He got interested, though, being a professional, and worked on it till nine-thirty.” That’s what a professional, a craftsman, is: a person who actually cares about, and becomes deeply engaged with working his best at, the job at hand.

[Photo Credit: Pictures of Westlake via Omnivoracious and Grantland; Drawing by Darwyn Cooke]