Our pals Eric Nusbaum and Craig Robinson were on hand for the Caribbean Series championship in Mexico. They’ve got a five-part series over at Sports on Earth.

Don’t miss it.

Our pals Eric Nusbaum and Craig Robinson were on hand for the Caribbean Series championship in Mexico. They’ve got a five-part series over at Sports on Earth.

Don’t miss it.

Originally published in the Post (April 8, 1969) and reprinted here with permission from the author, he’s a keeper for the Yankee fans out there.

“Something To Do With Heroes”

by Larry Merchant

Paul Simon, the Simon of Simon and Garfunkel, was invited to Yankee Stadium yesterday to throw out the first ball, to see a ballgame, to revisit his childhood fantasy land, to show the youth of America that baseball swings, and to explain what the Joe DiMaggio thing is all about.

Paul Simon writes the songs, Art Garfunkel accompanies him. They are the Ruth and Gehrig of modern music, two kids from Queens hitting back-to-back home runs with records. They are best known for “Mrs. Robinson” and the haunting line, “Where have you gone, Joe DiMaggio, a nation turns its lonely eyes to you.” Joe DiMaggio and 100 million others have tried in vain to solve its poetic ambiguity.

Is it a plaintive wail for youth, when jockos made voyeurs of us all and baseball was boss? “It means,” said Paul Simon, “whatever you want it to.”

“I wrote that line and really didn’t know what I was writing,” he said. “My style is to write phonetically and with free association, and very often it comes out all right. But as soon as I said the line I said to myself that’s a great line, that line touches me.”

It has a nice touch of nostalgia to it. It’s interesting. It could be interpreted in many ways. “It has something to do with heroes. People who are all good and no bad in them at all.That’s the way I always saw Joe DiMaggio. And Mickey Mantle.”

It is not surprising, then, that Paul Simon wrote the line. He is a lifelong Yankee fan and once upon a boy, he admitted sheepishly, he ran onto their hallowed soil after a game and raced around the bases.

“I’m a Yankee fan because my father was,” he said. “I went to Ebbets Field once and wore a mask because I didn’t want people to know I went to see the Dodgers. The kids in my neighborhood were divided equally between Yankee and Dodger fans. There was just one Giant fan. To show how stupid that was I pointed out that the Yankees had the Y over the N on their caps, while the Giants had the N over the Y. I just knew the Y should go over the N.”

There was a Phillies fan too—Art Garfunkel. “I liked their pinstriped uniforms,” he said. “And they were underdogs. And there were no other Phillie fans. Paul liked the Yankees because they weren’t proletarian.”

“I choose not to reveal in my neuroses through the Yankees,” said Simon, who was much more the serious young baseball sophisticate. “For years I wouldn’t read the back page of the Post when they lost. The Yankees had great players, players you could like. They gave me a sense of superiority. I can remember in the sixth grade arguments raging in the halls in school on who was better, Berra or Campanella, Snider or MantIe. I felt there was enough suffering in real life, why suffer with your team? What did the suffering do for Dodger fans? O’Malley moved the team anyway.”

Simon and Garfunkel are both twenty-seven years old. Simon’s love affair with baseball is that of the classic big city street urchin. “I oiled my glove and wrapped it around a baseball in the winter and slept with it under my bed,” he said. “I can still remember my first pack of baseball cards. Eddie Yost was on top. I was disappointed it wasn’t a Yankee, but I liked him because he had the same birthday as me, October 13. So do Eddie Mathews and Lenny Bruce. Mickey Mantle is October 20.”

Simon played the outfield for Forest Hills High, where he threw out the first ball of the season last year. Yesterday, after fretting that photographers might make him look like he has “a chicken arm,” he fired the opening ball straight and true to Jake Gibbs.

Then Simon and Garfunkel and Sam Susser, coach of the Sultans, Simon’s sandlot team of yesteryear, watched the Yankees beat the Senators 8-4 with some Yankee home runs, one by Bobby Murcer, the new kid in town. “I yearned for Mickey Mantle,” Paul Simon said. “But there’s something about that Murcer. . . .”

The conventional wisdom is that there are no more heroes who “are all good and no bad.” Overexposure by the demystifying media is said to be the main cause. Much as I’d like to, I can’t accept that flattery. Babe Ruth and Jack Dempsey were seen as antiheroes by many adults, as are Muhammad Ali and Joe Namath, but young fans always seem to make up their own minds.

Is it time for pitchers and catchers yet? Almost. In the meantime, dig this:

“Jim Bouton, Reliever”

Washington Daily News, 1969

Jim Bouton pitched an inning of relief for the Seattle Pilots Friday night, and two innings Saturday afternoon. That’s the way it is these days for Jim Bouton, 30, who started 37 games for the Yankees in 1964.

They were three pretty good innings for a guy who throws only one pitch. Bouton got almost everybody out and he got Frank Howard, on a one-two pitch, to pop up.

The trouble with Howard is that some of his pop-ups land in places where nobody can catch them. This one landed in the bullpen when it came off the wall That wasn’t bad.

What was bad was that Bouton’s hat never fell off. It hasn’t fallen off for a long time. It probably never will again.

The hat fell off when he labored in the vineyards of Auburn and Kearney and Greensboro and Amarillo. He is not a very big man, so he had to throw very hard to throw very fast. He knew he had to make it as a fastball pitcher or not at all.

Bouton came right over the top with the ball and the maximum effort made the fingertips of his right hand touch the ground as he followed thru. He needed all of it, all the time.

And the hat fell off. lt was still falling off when he won 21 games for the Yankees in 1963, and won half enough games to win the World Series in 1964.

Then he lost the fastball. Nobody believed he had lost it in 1965, when he went 4-15. He was lousy, but so, suddenly, were the Yankees.

By opening day, 1966, at Minneapolis, the truth was evident. He threw three consecutive change ups to Jim Kaat, a pitcher, and the third one beat him.

“I couldn’t throw the curve,” Bouton said yesterday. What he meant was that he could throw it, but unaccompanied by that fastball that hummed and darted, it didn’t fool anybody. He was Jim Bouton, fastball pitcher, and he had lost his fastball.

Two years ago the Yankees tentatively gave up on him and for the rest of the year, Bouton got knocked around in Syracuse. Last year they gave up on him unqualifiedly and shipped him to Seattle, which was still minor league.

Bouton didn’t give up. “I thought about quitting,” he said. “We talked about it a lot, but my wife is great. She just said, ‘Whatever you want to do.'”

Bouton wanted to pitch. He began throwing knuckle halls. “What could I lose? I was 0-7 in a minor league. I had thrown a knuckler as a kid, and I found out I could still throw it. After a while, I was getting it over.”

After a while he was 4-7. Maybe, he feels, he can still make it for a few years as a knuckleballer. And if he can’t, he feels, it’s no great tragedy. “I guess I’d sell real estate, or something,” he said. “I know I won’t work in an office. I’ll have to combine something to make a living, with something I really want to do.”

There are other things to think about. There is Kyong Jo Cho.

“Oh, sure,” Bouton said, “we could have had more children. But with the population situation what it is, I don’t think anybody has the right to have as many children as they can, where there are already so many children in the world that nobody is taking care of.”

Michael Bouton will soon be six and Laurie is almost four. For the past year, suburban New Jersey has been getting used to the fact that they have a middle brother named Kyong. “His mother was Korean,” Bouton explained. “His father was an American soldier. It’s not an advantage to have white blood in Korea.”

The Koreans, after several centuries of being whipping boys for the Japanese—being given in Japan the menial equivalent of Negroes in the American South—have finally found somebody of their own to be prejudiced against.

“We didn’t specify a Korean kid,” Bouton said. “We just told them we wanted a boy, and the age, and one with an aggressive personality.

“We did say we didn’t want a child with a Negro background. You know I don’t have anything against Negroes, but my wife and I had doubts about what kind of America it’s going to be 10 years from now.”

He had doubts about what kind of America it is right now. When Bouton came to the Yankees in 1962, he was brainwashed like all young Yankees about what not to say to newspapermen. He decided to make up his own mind and found that he even liked some of them. He horrified the senior Yankees by socializing with reporters.

He learned from the experience of a reporter his own age that adopting a Negro orphan could lead to unforeseen heartbreak and be a failure.

Kyong Jo Cho was on the way, so Jim Bouton went to Berlitz. “I learned how to ask him if he wanted a cab to his hotel,” Bouton said, “but I didn’t learn how to ask him, ‘Where does it hurt?’ So I took a cram course, and now a lot of kids in the neighborhood know how to say, ‘Where did he go?’ in Korean.”

It was, in a sense, a waste of time. Kyong has steadfastly refused to speak a word of Korean. He came to Bouton a few weeks ago and complained that all the kids were calling him Kyong.

“He said he wanted an American name,” Bouton said. “I asked what he thought about David. My wife and I had thought about that and we were hoping he would ask. He said that would be fine.”

David Bouton is a lucky kid.

Here’s another sure shot from the great Joe Flaherty (reprinted with permission from Jeanine Flaherty). You can find his story on Toots Shor, here; his wonderful piece on Jake LaMotta, here. Meanwhile, enjoy a…

“Love Song to Willie Mays”

by Joe Flaherty

When Willie Mays returned to New York, many saw it—may God forgive them—as a trade to be debated on the merits of statistics. Could the forty-one-year-old center fielder with ascending temperament and waning batting average help the Mets?

To those of us who spent our boyhood, our teens, and our beer-swilling days debating who was the first person of the Holy Trinity–Mantle, Snider, or Mays?–it was a lover’s reprieve from limbo. No matter how Amazin’ the Mets were, a part of our hearts was in San Francisco.

Mays was special to me as a teenager because I was a Giant fan in that vociferous borough of Brooklyn. This affliction was cast on me by a Galway father who reasoned that any team good enough for John McGraw was good enough for him and his offspring. So as boys, rather than take a twenty minute saunter through Prospect Park to Ebbets Field, the Flahertys took their odyssey to 155th Street, the Polo Grounds.

In that sprawling boardinghouse of a park I had to content myself with the likes of Billy Jurges, Buddy Kerr, and a near retirement Mel Ott whose kicking right leg at the plate was then a memory, no longer an azimuth which his home run followed. The enemy was as star laden as MGM: Reese, Robinson, Furillo, Cox, Hodges, Campanella, et al. So when Willie arrived in 1950, the Davids in Flatbush who had been hoping for a slingshot instead were bequeathed the jawbone of an ass.

Of course, we did have Sal Maglie, that living insult to Gillette, who thought the shortest distance between two points was a curve. But it was Willie who did it. It was he who gave the aliens in that Toonerville Trolleyland respectability. Even the enemy fan was in awe of him. He was no Plimptonesque hero about whom the beer drinkers in the stands fantasized. He was beyond that. His body was forged on another planet, and intelligent grown men know they have no truck with the citizens of Krypton. It has always amazed me to hear someone taking verbal vapors over the physical exploits of a ballet dancer while demeaning the skills of a baseball player. After all, is it not true that such as a Nureyev is practiced and choreographically moribund within a precise orbit I should swoon at such limited geography, when I have seen Mays ad lib across a prairie to haul down Vic Wertz’s 1954 World Series drive? No. Willie, like Scott Fitzgerald’s rich, is very different from you and me.

Yet, looking back on him (call it mysticism, if you like), I have the feeling his comet could have sputtered. This fall from grace, I feel, could have happened if he had come to bat in the final playoff game against the Dodgers in 1951. I was in the stands with a bevy of other hooky players, and I can’t help thinking Mays would have failed dismally if he had to come to the plate. He was just too young, a kid constantly trying to please his surrogate father, Durocher. Something dire surely would have happened: The bat would have fallen from his hands, or he would have lunged at the ball the way a drunk mounts stairs. Of course, this is all conjecture, since Bobby Thomson’s home run was his reprieve.

Still, let the mind’s eye conjure up the jubilant scene at home plate as the Giants formed a horseshoe to greet Thomson. Willie, who was on deck, should have been one of the inner circle, but he was on its outer fringes—at first too paralyzed to move, then a chocolate pogo stick trying to leap over the mob, leaping higher than all, which is an appropriate reaction from a man who has just received the midnight call from the governor.

But that’s rumination in the record book. Now, the day is Sunday, May 14, 1972, the opponent those lamisters from Coogan’s Bluff, Willie’s recent alma mater, the San Francisco Giants. The day was neither airy spring nor balmy summer but overcast and rain-threatening. I liked that—the gods were being accurate. This was no sun-drenched debut of a rookie; the sky bespoke forty-one years.

The park was as displeasing as usual. Shea Stadium is built like a bowl, and when one sits high up, he feels like a fly who can’t get down to the fudge at the bottom. An ideal baseball park is one that forces its fans to bend over in concentration, like a communion of upside down L’s. Ebbets Field was such a park.

The fans at Shea have always been too anemic for me. Even the kids with their heralded signs seem like groupies for the Rotarians or the Junior Chamber of Commerce: ”Hicksville Loves the Mets,” “Huntington Loves the Mets”; alas, Babylon can’t be far behind. And today the crowd was behaving badly, like an affectionate sheepdog that drools all over you. Imagine, they were cheering Willie Mays for warming up on the sidelines with Jim Fregosi! A Little League of the mind.

But there were dots of magic sprinkled throughout the meringue. The long-ago-remembered black men and women from the subway wars also were in attendance: the men in their straw hats, alternating a cigar and a beer under the awnings of their mustaches; the women, grown slightly wide with age, bouquet bottoms (greens, reds, yellows, purples) sashaying full bloom. These couples wouldn’t yell “Charge” when the organ demanded it (a dismal, insulting gift from the Los Angeles Dodgers), nor would they cheer a sideline game of catch. They were sophisticates; they had seen the gods cavort in too many Series to pay tribute to curtain-raising antics.

Mays was in the lead off spot, and one watched him closely for decay. Many aging ballplayers go all at once, and the pundits were playing taps for Willie. This (and a .163 batting average) roused speculation about Mays’ demise. Nothing much was learned from his first at bat. He backed away from “Sudden Sam” McDowell’s inside fast ball, a trait that is much more noticeable in him lately against pitchers who throw inside smoke. But he wasn’t feverishly bailing out, just apprehensively stepping back. Not a deplorable physical indignity but a small one, like an elegant man in a homburg nodding off in a hot subway. He walked, as did Harrelson and Agee after him. Then Staub, as if disturbed by the clutter, cleaned the bases with a grand slam. Mets 4–0.

His second time at bat I noticed he shops more for his pitches these days. There is a slight begging quality, where once there was unbridled aggressiveness. This time patience paid a price, and he was caught looking at a third strike. This was more disturbing. The head of the man in the homburg had just fallen on the shoulder of the woman next to him.

In the top of the fifth the Giants roughed up Met pitcher Ray Sadecki for four runs. Also in the course of their rally they pinch hit for their lefty McDowell, which meant that Mays would have to hit against the Giants’ tall, hard-throwing right hander Don Carrithers in the Mets’ bottom half. Bad omens abounded. If a left hander could brush Willie back, what would a right hander do? And now the game was tied, and he would have to abandon caution. Worse, the crowd was demanding a miracle, the same damn crowd which had cheered even his previous strikeout. The unintelligent love was sickening. He was an old man; let him bring back the skeleton of a fish, a single, this aging fan’s mind reasoned.

But one should not try to transmute the limitations that time has dealt him on the blessed. Even the former residents of Mount Olympus now and then remember their original address. Mays hit a 3-2 pitch toward the power alley in left center–a double, to be sure. I found myself standing, body bent backward like a saxophone player humping a melody, ’til the ball cleared the fence for a home run. The rest was the simple tension of watching Jim McAndrew in relief hold the Giants for four innings, which he did, and the Mets won, 5–4.

The trip home was romance tainted with reality. I knew well that Mays would have his handful of days like this. He still had enough skill to be a “good ballplayer,” though such a fair, adequate adjective was never meant to be applied to him. But life can’t be lived in a trunk, so I closed the lid on the memory of his lightning, and for a day, like an aging roué who has to shore up the present, I boldly claimed: “Love Is Better the Second Time Around.”

August 26, 1972

Here’s another gem from our man John Schulian. This column on Earl Weaver first appeared in the Chicago Sun-Times, August 16, 1981 (It can also be found in Schulian’s collection, Sometimes They Even Shook Your Hand). It is featured here with the author’s permission.

“The Earl of Baltimore”

By John Schulian

BALTIMORE—Based on the available evidence, it is easy to assume that Earl Weaver perfected managerial sin. After all, the profane potentate of the Orioles has spent the past thirteen seasons kicking dirt on home plate, tearing up rule books under umpires’ noses, and generally behaving as if he were renting his soul to the devil with an option to buy. Yet here it is the middle of August and he has only been kicked out of one game. Reputations have been ruined for less.

Understandably, Weaver is not pleased to hear that his dark star appears to be fading. In his corner of Memorial Stadium’s third base dugout, he looks up from a pregame meal of a sandwich and a cigarette and searches the horizon for an explanation. “Musta been the foggin’ strike,” he says at last. “Guys like me, I coulda got tossed five foggin’ times in the time we were off. I’m streaky that way.”

Satisfied, he resumes dining only to be interrupted moments later by Jim Palmer, the noted pitcher and underwear model. With a mischievous smile, Palmer raises his voice in a song that suggests one more reason why his fearless leader has been wont to raise hell with umpires: “Happy Birthday.”

“Oh,” Weaver says, “you remembered.”

“Of course,” Palmer says.

“I know why you remembered, too,” Weaver tells his favorite rascal. “You know that at my age, it’s gotta hurt.”

He has turned fifty-one on this gray Friday, but there will be no party for him. The Orioles will play the White Sox, and then Earl Weaver, the owner of a full head of hair and none of his own teeth, will go home to be with his wife and his prized tomato plants. He will go home to rest, to savor his stature as the winningest manager in the big leagues, and to get away from all the insufferable questions about how the White Sox are pretending to be a new and improved version of the Black Sox.

They have been quoted anonymously in the press as saying they would throw games at the end of this split season if it would help them get into the playoffs. The mere suggestion of such chicanery has horrified the lords of baseball and forced the team’s management to talk faster than a married politician photographed in the arms of a Las Vegas strumpet. To Weaver, who once marched his team off the field in Toronto to save his bone-weary pitching staff, the Sox’s scheme sounds like the work of dummies.

“What the fog,” he says. “The White Sox better not lose too many foggin’ games deliberately or they’re not gonna be in it. The simplest thing for them to do is win as many games as they can and root like hell for foggin’ Oakland. Look at us, we’re in the same boat. We gotta hope New York beats every-foggin’-body except us. Ain’t that something? I gotta root for them damn pinstripes.”

Nobody said the split season would honor tradition. Indeed, there are those who believe that cutting the season in half smacks more of the old Georgia-Florida League than it does of the American or the National. “Oh, no you don’t,” says Weaver, who spent his playing career in towns where two cars on Main Street constituted a traffic jam. “I don’t want no foggin’ headline sayin’ WEAVER CALLS SPLIT SEASON BUSH.” As a matter of fact, if he had his way, every season would have two chapters, strike or no. “If you start bad,” he says, “it’s nice to be reborn again.” When was the last time Bowie Kuhn addressed any issue so eloquently?

The next thing you know, Weaver will find himself running for commissioner when all he really wants to do is figure out a better way to handicap horse races. That’s the way baseball works: What’s dumb gets done. So lest the game’s kingmakers get the wrong impression from his bleats about old age and his apparent flirtation with respectability, Weaver tries to erase some of the points he has scored with the establishment. The best way to do that is to discuss the fine art of making umpires look like donkeys.

He remembers hearing how a minor league manager named Grover Resinger responded to being given five minutes to get off the field and out of the ballpark. “He asked if he could see the umpire’s watch,” Weaver says, “and when the dumb fogger handed it to him, Resinger threw it over the top of the foggin’ grandstand.”

Then there is Frank Lucchesi, an old sparring partner from the Eastern League. Once, Lucchesi sat on home plate until the police came and carried him into the dugout. Another time, after being ordered off the premises, he climbed the flagpole behind the outfield fence and flashed signals to his team from there. But what Lucchesi did best was drive Weaver to heights of creative genius.

“I forget what the foggin’ call was,” Weaver says, “but the umpire blew it, so I went out and talked like a Dutch uncle and they changed it back. Then Lucchesi comes out and he talks like a Dutch uncle and they change it back. I’m standing there on the mound talking to my pitcher, and when I see them do this, I grab my foggin’ heart and fall on my face. Right there on the mound.

“One of my players comes runnin’ out and rolls me over and starts fannin’ me with his cap. The umpire is right there with him. He says, ‘Weaver, if you even open one eye, you’re out of this game.’ Well, hell, by then, I couldn’t resist, and you know what I saw? There was Lucchesi with one of them old Brownie box cameras. He told me later it was the greatest foggin’ thing he’d ever seen.”

A mischievous smile creases Weaver’s face. “Hey,” he says, “maybe I oughta do that again.”

It could save his reputation.

From his fine collection, Sometimes They Even Shook Your Hand, here is John Schulian on Stan the Man:

Of all the heroes I encountered, though, the one who best fit the description was Stan Musial, who managed to be a regular guy even with a statue of him standing outside old Busch Stadium, just as it does now in front of new Busch. In 1982, with the Cardinals on their way to the World Series, it seemed fitting that I should write about him. We met at the restaurant that bore his name, and as soon as I mentioned an obscure teammate of his—Eddie Kazak, a third baseman in the forties—it was like we were old friends.

When I finally ran out of questions, Musial offered to drive me back to my hotel. We made our way through the restaurant’s kitchen, pausing every few steps so he could say hello to a cook or slap a dishwasher on the shoulder. At last we reached the small parking lot in back. The only other people in sight were two teenaged boys with long faces. Musial was unlocking his Cadillac when one of them said, “Hey, mister, you got any jumper cables? Our car won’t start.”

“Lemme see, lemme see,” Musial said. He repeated himself a lot that way. It only added to his charm.

He opened his trunk and started rooting around, pulling out golf clubs, moving aside bags and boxes until, at last, he found his cables. By then, however, I was more interested in watching the boys. One of them was whispering something to his buddy and I could read his lips: “Do you know who that is? That’s Stan Musial.”

The statue in front of the ballpark had come to life.

Rest in Peace, Earl Weaver. One of the memorable characters and greatest managers of his or any other time.

Here’s a bit of Weaver for you, the chapter I wrote about the 1974 American League East for It Ain’t Over ‘Til it’s Over:

Lou Piniella rounded second base with a full head of steam. He was a big, handsome man in a square-jawed Nick Nolte kind of way, only with dark hair. It was almost the end of spring training in Florida, and Piniella was pissed off. He had been running hard for weeks and had hated every minute of it. First-year Yankee manager Bill Virdon ran the most disciplined camp that Piniella had ever been a part of. He was now completing a running drill that Virdon used to end practice sessions, in which each player would run from home to first, then first to third, third to home, home to second, second to home, home to third, and to cap it off, a last turn all around the bases.

When new Yankee general manager Gabe Paul traded for the 29-year old Piniella in the off-season, the outfielder came with a reputation as an indifferent fielder. Virdon firmly believed in conditioning and drilled his outfielders particularly hard. He knew he could make Piniella into a competent fielder and base runner.

Piniella rumbled around third as Virdon stood with his arms folded behind home plate. Then Piniella lost his footing, wobbled, and finally wiped-out. His face was red when he picked himself up off the ground and yelled at his manager. On all fours, Piniella crawled the rest of the way to the plate, cursing loudly. Virdon laughed, but later said, “as hard as I made Lou work, he never refused to do anything I asked him to do. And he became a very good left fielder.” That spring, Piniella displaced Yankees veteran Roy White as the team’s left fielder.

Virdon, 42, wore wire-rim glasses and had the bland but sturdy good looks of a career military man; he was unafraid to show off his physique in the clubhouse as a means of intimidation, a tactic that did not sit well with many of his players. Virdon had been a wonderful defensive center fielder in the major leagues. As a manager, he led Pittsburgh to a division crown in his rookie campaign in 1972, but was fired the following year with two weeks left in the regular season when the team underachieved.

When the Yankees hired Virdon he was clearly their second choice. That off-season, owner George Steinbrenner—who less than a year earlier declared that he was not interested in the day-to-day operations of the team—very publicly courted newly available skipper Dick Williams, winning manager of consecutive World Series with the 1972 and 1973 Oakland A’s. It was a boffo move by the Yankees, the first of many for Steinbrenner. But Oakland owner Charlie Finley successfully argued that Williams was still under contract and demanded lavish compensation in the form of the Yankees’ best prospects. The teams were unable to come to an agreement and the Williams deal was nullified. Explaining the Yankees’ decision to hire Virdon, Paul said, “We had to do something.”

In spite of his status as a consolation prize, Virdon brought a sense of organization and purpose to a Yankee team that featured some outstanding players but was chiefly comprised of likable guys who weren’t particularly caught up in winning. The previous year, the team made a run for the division title only to be physically exhausted in September. “We died,” said infielder Gene Michael.

The arrival of Steinbrenner, now in his second season as owner of the Yankees, had already sent manager Ralph Houk, a franchise fixture and player favorite, packing. Michael Burke, the public face of the team during the CBS years was gone too. Fresh flowers on the secretaries’ desk were a thing of the past. Virdon was the ideal man to enforce Steinbrenner’s Spartan new order on the field. Yankee players hadn’t been put through this kind of rigorous spring training in years.

The Yankees were going back to school, but the Orioles were already the most fundamentally sound organization in the game. The class of the American League East, the Orioles were coming off four division titles in five years. In five-and-a-half seasons as manager, Earl Weaver, an irascible and brilliant stump of a man, averaged 99 wins a year and three-and-half packs of cigarettes a day. Weaver never made the big leagues, but he became a part-time player/manager in the minors by the time he was 26. Harry Dalton, the assistant farm director for the Orioles, liked what he saw in the feisty young manager, who, in 11 full minor league seasons, finished either first or second eight times.

During the off-seasons, Weaver toiled in construction before landing a job as a loan officer. “Between my blue collar jobs and minor league baseball, I have been with every kind of person,” Weaver told Terry Pluto years later. “I know people. All types. I have heard all the sob stories about the checks being in the mail or waiting just one more week until payday. Listen, I could look into people’s eyes and see if they would pay.”

Weaver applied his intuitive psychological skills to managing. “Everything Earl did was calculated,” remembered Pat Gillick, a star pitcher for Weaver in Fox Cities. He wouldn’t ask players to do something they weren’t capable of, and was an avid believer in platooning. Weaver was also careful not to become emotionally attached to his players. He had no qualms about getting in their faces and berating them, ensuring that no mental mistakes went unnoticed. “I knew Earl would not be afraid to make moves,” said Dalton, who became the Orioles GM in 1966 and held the position for six years. “He is an aggressive guy who doesn’t back down for anyone.”

“I can’t be friends with players,” Weaver said later. “How can I when I may have to bench them or send them to the minors?”

And often, his players didn’t like him in return. Jim Palmer, Doug DeCinces, and Rick Dempsey would have celebrated rifts with Weaver over the years. “He doesn’t say much to anybody,” recalls Kiko Garcia, who played for Weaver from 1976 through 1980. “He talks a lot to everyone in general, but it is rare to have a conversation with him.” Second baseman Bobby Grich, remembers that during his rookie year in Baltimore, Weaver didn’t say more than five words to him all season.

“I never miss anything about the Orioles,” Grich said later. “The only thing I liked about Maryland was the crabs.”

Weaver was usually irritated once a game began and didn’t stop grumbling, then yelling, until it was over. “You do get this negative feeling from the start,” Garcia said. “But I’ll say this for the man, he doesn’t talk behind your backs. If he has something to say to you, he says it. And Earl let’s you say whatever is on your mind. You say it and then it is forgotten.”

“Earl does not have a shithouse like some managers,” says Mark Belanger who played for Weaver in the minor and major leagues. You can argue with Earl for six hours and call him every name in the book. But if he thinks you’re going to help him win, you’ll play the next day.” Weaver would have his favorites over the years—Belanger, Don Buford, and later, Eddie Murray and Ken Singleton—but playing for Weaver was never easy. When Oriole players were once asked what they would give Weaver for his birthday, one said, “One day in the big leagues so he’d find out that it’s not so easy.” Another said, “Nothing. He didn’t give me nothing on my birthday,” while still another teammate said, “An umpire crew which is his size so he could argue with them eye-to-eye.” (186-187, Earl of Baltimore)

Weaver had a rabbinical knowledge of the rulebook, and while he could abide growing pains in young players, he would not tolerate novice mistakes made by the umpires. Weaver’s run-ins with the men in blue became the stuff of legend. One year in Elmira, Weaver was so upset with a call that he carried third base off the field, then locked himself and the bag in the clubhouse. It took 10 minutes before a member of the grounds crew could get it back.

In the winter of 1961, the Orioles gave Weaver the task of designing the spring training regimen for the minor league program from double-A down; his system was later adopted throughout the entire organization. Weaver was the first manager in the team’s brief history to rise through the ranks, and he firmly believed in promoting coaches too, rewarding performance and, more importantly, maintaining a sense of continuity throughout the system. Many of Weaver’s greatest players, including Jim Palmer, Mark Belanger, Paul Blair, and Boog Powell, were from the team’s farm system. They were so well-versed in the fundamentals of the game—particularly the importance of mental focus—that they virtually policed themselves.

Yet for all of their success, the Orioles had only won the World Series once for Weaver. They were perceived as a bland, even boring team, certainly one without a national following. Even in Baltimore, they were distinctly second class citizens to the Colts. Attendance, which had peaked at 1.2 million in 1966, had dropped to just under 900,000 in 1972 and refused to pick back up again. One night, a streaker ran across the field. He was subdued by the police and brought before the Orioles’ GM, Frank Cashen, who said, “Give him $50 and tell him to come back tomorrow night.”

Virtually everything about Red Sox pitcher Luis Tiant was funny: he looked funny, sounded funny and even pitched funny. The only ones not in on the joke were opposing hitters.

Tiant, listed at 32 but believed to be as old as 40, was a stocky, dark-skinned man, with long side-burns, a Fu Manchu mustache, and a bulldog mug right out of a Looney Tunes cartoon. He had a high, piercing voice to match. When he pitched, his cheek, stuffed with chewing tobacco, puffed into a ball, emulating his ample pot-belly.

Tiant’s delivery was all of a piece. He twisted into a pretzel, completely turning his back to the hitter while looking out into center field. He then jerked back around and whipped the ball to the plate, throwing from three-quarters, over-the-top, as well as sidearm. Tiant had several different fastballs, a curve ball, palm ball, knuckle ball, forkball, and a hesitation pitch. Depending on the hitter and the situation, he could be deliberate, taking a long time between pitches; other times, he would sneak in a pitch before the hitter was ready. He also had a wicked pick-off move.

Oakland slugger Reggie Jackson gushed, “It’s not the dancing that gets you, though. That’s show business. It’s the fastball on the inside corner. That’s what kills you. While he’s turning around doing his dance, that ball is coming in on the black.”

Tiant smoked eight-inch black cigars everywhere but on the mound—sitting at his locker, in the whirlpool, even in the shower. He would stand in the clubhouse, naked except for his black socks, holding court and busting chops in a way that only few players can. Even Carl Yastrzemski, the team’s undisputed star was not immune to Tiant’s needle, and was accordingly dubbed “El Polacko.” Outfielder Reggie Smith once said that Tiant was “a guy who wakes up every morning of his life with something funny to say.” After Red Sox outfielder Tommy Harper played a poor game, Tiant reassured him, “Tommy, don’t worry because you played like shit and looked like shit. You only smell like shit.”

Boston had signed the aging star pitcher Juan Maricial for $125,000 in the off-season, hoping to provide depth behind Tiant and Bill Lee, their two most reliable pitchers. Rick Wise came over for Reggie Smith, as did starter Reggie Cleveland and reliever Diego Segui. Rookie manager Darrell Johnson had a mix of veterans in Yastrzemski, Harper, Rico Petrocelli, and youngsters like Rick Burleson (shortstop), Cecil Cooper (first base), and Juan Benequiz and Dwight Evans (outfield), with the organization’s two prize prospects, Jim Rice and Fred Lynn waiting in the wings at Triple-A. But Maricial and Wise were hurt early on, and Carlton Fisk, the team’s All-Star catcher was lost for the season in June to a knee injury.

Tiant rebounded from a sluggish start and the rest of the team followed. Yastrzemski had a strong first half (.331/.431/.502), as did Burrelson (.317/.352/.431), about whom Bill Lee later said, “I had never met a red ass like Rick in my life. Some guys didn’t like to lose, but Rick got angry if the score was even tied.” After starting the season 2-5, Tiant went 18-4 with a 2.22 ERA over his next 22 starts. He completed seventeen of those games, tossing five shutouts in the process. The Red Sox reached first place on July 14th and remained there throughout August. Even when the team slumped, Tiant was there to save them—he won nine straight times during that summer following a Red Sox loss.

On August 23rd, Tiant faced Vida Blue and the World Champion Oakland A’s at Fenway Park. He was gunning for his 20th win of what The Boston Globe referred to as, “the happy season.” The paper also ran a “This Day in 1967” feature each day, a reminder that miracles really do come true. The Sox were six-and-a-half games in front of Cleveland, and seven games in front of both the Orioles and the Yankees (with Milwaukee and Detroit under .500 at the bottom of the division). For Sox fans, it was “a midsummer night’s dream brought to life,” wrote Leigh Montville in The Globe.

The largest crowd in 18 years packed Fenway Park. Tiant treated them to a vintage performance. He threw mostly breaking pitches in the early innings, saving the hard stuff for later. The A’s put men on base, and had their chances, but they could not score. Tiant got out of every jam, dazzling Oakland with his repertoire of pitches and deliveries. “With Luis, it’s not the stats, it’s the show,” noted Bob Ryan after the Sox won 3-0.

With just over a month left in the season, Boston was flying high. “The Red Sox fan had forgotten his inbred pessimism,” wrote Monteville several weeks later, “his rooting heritage. He had stuffed it in a drawer.” But there were signs of trouble. Tommy Harper’s first inning home run was the first Boston had hit since August 9th.

The Orioles found themselves in unfamiliar territory as well. Their ace pitcher, Jim Palmer, a twenty game winner in each of the past four seasons, was lost for a bulk of the summer with an arm injury, and would post the first losing record of his career (7-12, 3.27 ERA in 178 innings). Pitchers Ross Grimly and Dave McNally were outstanding, but Baltimore’s offense was a dud. Other than second baseman, Bobby Grich, nobody was having a better season than the year before. Left fielder Al Bumbry, who had been the league’s Rookie of the Year award winner in 1973, dropped from .337/.398/.500 (.321 EqA) to an unproductive .233/.288/.304 (.240 EqA). Another 1973 rookie, outfielder Rick Coggins, had hit .319/.363/.468 (.299 EqA). Now he slumped to .243/.299/.319 (.253 EqA).

Instead of concerning themselves with World Series shares, the Orioles were worried about surviving. The veteran players revived the Kangaroo Court in attempt to jump-start the club. The Court had been a staple feature of the Orioles locker room during Frank Robinson’s heyday with the team. The purpose of the court, which convened only after victories, was the issue fines for infractions both real and imagined.

“The court gets everybody to relax and brings us closer together,” said outfielder, Don Baylor. “It keeps guys from showering real quick and running out of the clubhouse.”

Fines were one dollar. Veteran catcher Elrod Hendricks was appointed Judge by his teammates. He objected but was overruled. In short order, Tommy Davis was fined for wearing a Chicago Cubs T-shirt, Paul Blair was nabbed for jogging to the outfield with a bar of chocolate in his back pocket and Earl Williams was called-out for hotdogging it around the bases after hitting a home run against the Twins. Williams said he wouldn’t mind paying the dollar fine if it meant he’d keep hitting home runs. But in spite of the newfound looseness in the clubhouse, the Orioles continued to flounder.

Five days after Tiant’s gem against the A’s, the Orioles held a team meeting at Paul Blair’s house. Baltimore had just dropped their fourth straight, and their record was 63-65. Brooks Robinson and Blair led the meeting but all of the veterans, spoke. They talked about doing “the little things,”—stealing, sacrificing, putting on the hit-and-run—playing a brand of baseball generally disdained by their manager. Weaver had been mixing and matching combinations of lineups and platoons for weeks to no avail. The players felt they couldn’t just wait around for Weaver’s cherished three-run home runs. Boston’s grip on first place wasn’t insurmountable. If they had to defy Weaver, so be it. Most importantly, it was agreed, if they were to have any success, the players would have to be unified. After all, Weaver couldn’t fight the entire team.

Don Baylor, an imposing young player who possessed both speed and power, admired the veterans on the team, and didn’t dare object, but later admitted, “Deep down inside, though, I was scared. There I was, my third year in the big leagues and about to enter into rebellion against Weaver and take orders from Brooks, Blair and Palmer.”

The next night, with the Orioles down 2-1 in the fourth inning, right fielder Enos Cabell singled. Belanger, the number nine hitter, bunted, and reached on an error. Baltimore scored three times in the inning and won the game, 6-2. The following night, Cabell reached first on a dropped third strike leading off the top of the second inning (the O’s already had a 3-0 lead). Belanger sacrificed him to second. In the fifth, with the Orioles ahead 5-1, Robinson singled and Blair bunted him to second.

The O’s reeled off four straight wins since their team meeting, including one by Palmer fresh off the disabled list, and trailed Boston by just five games when the two teams met in Baltimore for a double-header on September 1. “I don’t know which is harder,” Weaver told reporters, “to be behind and trying to catch up, or to be ahead and always worrying about losing your lead.”

“This is bad on the heart,” Paul Blair said. “I’m afraid someone will hit a ball to me and I’ll mess it up.” “The pressure and emotional strain are exhausting,” added Brooks Robinson. “I’ve never been through anything like this except during the playoffs and World Series.”

Luis Tiant pitched the first game and had no trouble until the fourth when he threw Bobby Grich a hesitation pitch with nobody on base. Grich was looking fastball but adjusted, and flat-footed, hit the ball just right, launching his 18th home run of the year. It was all the run support Ross Grimsley would need as the Orioles beat the Sox, 1-0. Mike Cuellar and Bill Lee pitched in the second game. In the third inning, Robinson and Cabell led off with singles. Utility catcher, Andy Etchebarren bunted poorly up the first base line and the runner at third was forced out. Belanger followed with another bunt—a sound play considering how terrible a hitter Belanger was, and reached first on a single. Blair followed with a sacrifice fly, giving the O’s a 1-0 lead. Later, in the sixth inning, Belanger reached on a bunt single. Blair bunted into an out, before Grich slapped into a double play. The players’ small ball strategy of playing for one-run was accomplishing just that. Grimsley was sensational and Baltimore won again, 1-0. Boston was devastated.

“That evening I lashed my hands to the bathroom sink,” Lee later wrote. “My hotel room was on the eighteenth floor, and I did not want to risk the temptation of walking near an open window.”

After a day off, Palmer shut-Boston out again, this time 6-0. “If we have Palmer, we’ll win,” Grich told reporters. The Red Sox managed a total of eight hits for the entire series, and had lost their last six games while Baltimore won it’s seventh in a row. Then Boston dropped the next two games to the Brewers and fell into second place behind the hard-charging Yankees.

The Orioles shut out the Indians in their next two games. The following night, George Hendrick doubled off Grimsley in the fourth inning; it was the first extra base hit against the O’s in a whopping 71 innings. Grimsley held a 3-0 lead in the ninth inning before allowing a two-run homer. The O’s won again, their tenth in a row. The scoreless streak, 54 consecutive innings, was a major league record. Weaver later called it “the most amazing pitching performance by a staff” that he had ever seen.

Gabe Paul, dubbed “Dial-a-Deal” by Yankee players, worked diligently to upgrade the team during the season. He used the Yankees’ deep pockets to purchase outfielder Elliot Maddox, and infielders Jim Mason and Sandy Alomar, all valuable contributors. Maddox was the team’s best outfielder, and loved the manager’s fly ball drills. “He’d wear out the other guys, but I would still yell for more,” Maddox recalls.

When the Yankees best pitcher Mel Stottlemyre tore his rotator cuff in June—an injury that would end his career—Paul bought veteran lefty Rudy May, who went 8-4 with a 2.28 ERA in 17 games for New York. But Paul’s biggest move came at the end of April when he shipped four pitchers, starters Fritz Peterson, Steve Kline, and relievers Fred Beane and Tom Buskey to Cleveland for first baseman Chris Chambliss, and pitchers Dick Tidrow and Cecil Upshaw. The quartet of Yankee pitchers was enormously popular in the clubhouse and the team was livid.

“How can we trade half a pitching staff?” said Stottlemyre.

“At this rate, the Indians are going to have a pretty good ball club soon,” moaned center fielder Bobby Murcer.

During the 1974 and 1975 seasons, the Yankees played their home games at Shea Stadium while Yankee Stadium was undergoing massive renovations. “It was like we were guests there, and every game was an away game,” said Doc Medich, the team’s best starting pitcher. The field, shared by two clubs, was in horrible condition, and bored Met fans occasionally showed up simply to heckle the Yankees.

Nobody on the team suffered more than Murcer. Unable to pop home runs over a short fence in right field, as he did at Yankee Stadium, Murcer instead hit countless fly balls to the warning track at Shea. Over the previous two seasons Murcer had hit 55 home runs. In 1974, he hit just ten, eight on the road.

At the end of May, Virdon moved Murcer to right field, replacing him in center with Maddox. It was a courageous move for Virdon, displacing the heir to Mickey Mantle. Murcer was better suited to right (his 21 assists led the league), but his ego was bruised and he was miserable: he could not sleep, and refused to speak to Maddox.

Despite Murcer’s bitterness, the move seemed to spark the Yankees, and the team flourished in the second half. Sparky Lyle, who, like Ted Simmons two years earlier, was playing without a signed contract, was again brilliant (9-3, 1.66 ERA in 114 innings); Graig Nettles hit 11 home runs in April and was coming into his own as a fielder, and both Piniella (.305/.341/.407) and Roy White (.275/.367/.393) were solid contributors. Maddox was a surprise offensively (.303/.395/.386), establishing career highs in doubles, and on-base percentage. Before and after each game, he played the song “Band on the Run,” the song by Paul McCartney & Wings that had reached the top of the charts in June.

The biggest trouble for the team involved their not-so-absentee-owner. On Friday, September 6th, George Steinbrenner was ordered to sever all contacts with his club by commissioner Bowie Kuhn. Steinbrenner had been found guilty earlier in the year of making illegal campaign contributions to Richard Nixon’s re-election campaign. Now Kuhn, in an uncharacteristically assertive move, made a public example of Steinbrenner forcing him to cut ties with the team.

The Yankee owner was partial to addressing his players as if they were a college football team; he had spoken with them several times after losses earlier in the season. Now, he was forced to send them pre-recorded pep talks. Virdon was instructed to play the cassettes for the team in the locker room. “Goddamn it, you’ve got to go balls-out all the time,” Steinbrenner implored on the tape. “You’ve got to have balls!”

The Yankees and Sox were tied for first when New York arrived in Boston for a two-game series on September 11th. Baltimore was just a game back. The Yankees had lost 20 of their previous 21 games at Fenway Park. “It’s a little bit scary,” Piniella confessed, but the Yankees won the first game, 6-3. Tiant was on the mound the following night when Boston needed him most. “Some guys can’t pick up the pot,” Gabe Paul told Sports Illustrated, “but Luis’ nostrils dilate when the money is on the table.”

Tiant held the Yankees scoreless through eight innings, the Sox clinging to a slim 1-0 lead. Lou Piniella drew a one-out walk in the ninth and was replaced by pinch-runner Larry Murray, who raced home when Chris Chambliss’ line drive bounced around the right field corner. By the time right fielder Dwight Evans returned the ball to the infield, Chambliss was on third. Evans rushed in from right and screamed for fan interference. The umpires huddled and eventually sent Chambliss back to second with a ground-rule double. But they also allowed Murray to score, a dagger for the Sox.

Before Chambliss could return to second, he felt a thud in his arm. He looked down and found a steel dart embedded in it. A half a dozen more darts lay on the ground next to him, thrown from the third base stands (Chambliss would need a tetanus shot, but remained in the game). Alex Johnson, a veteran slugger purchased by New York a day earlier, hit a solo home run off Diego Segui in the twelfth inning and the Yankees were suddenly two games ahead of the Sox.

The following day, the Band on the Run Yankees split a double-header in Baltimore, losing the first game in 17 innings. Grimsely surrendered just two runs in 14 innings and Boog Powell, finally swinging a hot bat, singled home the game-winning run. A week later, they were still in first place, 2.5 games ahead of the Orioles, three-and-a-half in front of Boston, with Baltimore in town for a three-game series.

“If we win two out of three from Earl,” Piniella told Murcer, “we win this thing.” Murcer advised his teammate to stay away from the Orioles manager. Piniella had a past with Weaver, who he played for in Elmira, 1965. They got into a fight the first time they met and then grew to dislike each other. Before the end of that season, Weaver suspended Piniella for insubordination. According to Weaver’s memory, Piniella had to pay for thee water coolers, four doors and at least fifteen smashed bating helmets that season. The tension between the two would continue throughout the years. It’s just that Weaver could not resist tweaking such a red ass as Sweet Lou Piniella, who ironically would always hit very well against Weaver’s teams. That’s why Weaver busted his chops. Weaver would give Piniella a piercing whistle whenever Lou popped-up or grounded out.

“Lou may be like the proverbial pile of dogshit,” Weaver wrote years later. “It never bothers you until you step in it. He has to be one of the best damn ‘guess’ hitters I’ve seen. And he’s a patient hitter too.”

One day in 1976, Piniella almost charged Weaver, who refused to stop baiting him while he was hitting (“Don’t hit a home run.”). After striking out, Piniella moved toward the Orioles dugout only to be restrained by teammates. Weaver darted towards the clubhouse. Years later, the writer Dick Lally asked Weaver why he ran. “Did you know he was the kind of guy who would chase you?” “Worse,” Weaver replied, “he’s the kind of guy who’ll catch you.”

As the Yankees took batting practice, Weaver approached Piniella, took off his hat and scratched his head, tilting it to the side. He looked directly at Piniella and said, “I keep reading the papers about your great catches and great throws. Why didn’t you do that for me in Elmira?”

Piniella smiled and then got into the cage and took his hacks. When he was finished Weaver was still standing there and he said, “You know what, I’m going to jinx you. I know damn well there’s going to be a play later on this season and you’re going to screw it up and miss a ball in the outfield, and that will give us the damn pennant.”

“You’re crazy,” said Piniella.

The Orioles proceeded to sweep the Yankees, jumping into first place, with Palmer and McNally tossing shutouts. The Baltimore players congratulated themselves, feeling their rebellion had worked. Initially, Weaver was confused as to why his signals were being ignored, but he caught on soon enough. Don Baylor came to bat one night with runners on first and second against the White Sox and ignored third base coach Billy Hunter’s signal for a sacrifice (issued by Weaver). Brooks Robinson, waiting on the on-deck circle, made eye-contact with Baylor and indicated that he should swing away. Baylor smacked a run-scoring single to left, his third hit of the game. When he returned to the dugout Weaver snarled at him, “You had better be glad you got that hit.” Still, as the veterans had predicted, Weaver couldn’t jump the whole team.

“Knowing Earl,” Baylor later wrote, “he probably thought it was funny. He loved defiance. He probably said under his breath, ‘Those sons of bitches…I know what they are doing, but they’re winning.’ And that’s the only thing that ever really mattered to Early anyway.”

Had the players’ rebellion really carried the Orioles? The change in play was less than revolutionary. The 1974 team was one of the weakest offensive units the Orioles had put on the field since Weaver had been manager. The team’s production at bat had peaked in 1971, but since then Boog Powell had been weakened by injuries, Brooks Robinson had declined, and slugger Frank Robinson had been traded in what proved to be an ill-advised application of Branch Rickey’s dictum that it’s better to trade a player a year early than a year too late. By 1974, Weaver said, “it had been three years since we’d been paid an extended visit by Dr. Longball.”

Weaver adjusted. Though never a fan of the bunt and run game (“I’d rather have more three-run homers,” he said. “Then everyone can take their time and stroll home. I’ve never had a baserunner thrown out once a ball’s been hit over the fence.”), he recognized that the team could no longer slug its way to victory. The Orioles began running, leading the league with 146 stolen bases—but they did this in 1973, not 1974. They stole 145 bases in 1974, but this was a continuation, not a change of direction. The Orioles did make more sacrifice bunt attempts than they had in 1973, the total rising to 119 from 104.

With the acquisition of Ken Singleton and Lee May in the 1974-1975 offseason, Orioles power production rose and there was less reason for the players or the managers to worry about the bunt. The O’s made 21 fewer attempts in 1975, but were successful a far greater percentage of the time, executing 73 sacrifices in 98 attempts versus 72 in 119. This suggests that even if the players were calling the shots on bunts in 1974, they would have been better off leaving the decisions in Weaver’s hands.

The Orioles stole more bases had had more sacrifice bunts in September than any other month during the season. On the other hand, they had their second-highest home run total of any month, and their highest OBP, and the most amount of walks. The small ball certainly helped jump start the action, but what was likely more responsible for the resurgence of the Baltimore offense were strong months from Blair (.301/.377/.513), Baylor (.400/.441/.600) and Powell (.342/.528/.658).

After New York, the Orioles went to Boston and beat the Red Sox twice in three days. After the third game (a Baltimore win), at 5:05 on Sunday, September 22nd, a young man stood behind the Boston dugout and played taps on a bugle. The Sox were five games out of first place. New York, in the meantime, won their next four games, and were a game ahead of the Orioles when Boston arrived in New York for a three-game set, beginning with a twi-night doubleheader. There was an autumn chill in the air at Shea Stadium as more than 46,000 fans watched Tiant win his first game since August 23rd, as the Sox blanked the Yanks, 4-0. Peter Gammons reported that the ensuing scene at Shea was akin to a “Chilean soccer riot:”

Tennis and rubber balls showered from the upper deck, beer was poured on players, trash littered the field and all the while, fights—street brawls—broke out everywhere. They were on the field, in the stands, and one between a man and the police ended up in the Red Sox dugout. It just hadn’t gone the way it was supposed to go, and the Orioles had beaten Detroit, 5-4 to take first.”

Boston also won the second game, this time 4-2. The following day, the Orioles won another close one, scoring three in the ninth inning after trailing by two. Baltimore simply would not relent. Doc Medich out-dueled Bill Lee at Shea Stadium, 1-0 before a “comparatively quiet” crowd according to Gammons. “The first fight didn’t come until the fourth, the first bottle thrown from the upper deck didn’t come until the sixth and Boston third base coach Don Zimmer didn’t need to his batting helmet until the seventh.” With seven games left, the Red Sox were cooked.

On Sunday, September 29th, the Yankees waited out bad weather in their Cleveland hotel, as they prepared to end the season in Milwaukee. With two games left, the Yankees trailed Baltimore by just one. The Orioles were in Detroit playing the Tigers. Eventually, the Yankees made it to the airport only to find that their flight was delayed. While waiting, many of the players got loaded. By the time they finally reached Milwaukee, back-up first baseman Bill Sudakis and reserve catcher Rick Dempsey, two large but thin-skinned men, were at each others throats. The two got tangled together in the revolving door as the team was checking-in to their hotel, and emerged throwing punches. Their teammates scrambled to separate them. In the commotion, Murcer was tossed to the floor. A teammate stepped on his hand but Murcer was too drunk himself feel the pain. Sudakis and Dempsey were finally subdued, as Murcer lay pale-faced on the ground.

When Murcer woke up in the morning, his hand was in bad shape. The biggest game of his Yankee career and he was unable to play—a fitting end to a misbegotten season (Before the end of the month, Murcer was traded to the Angels for Bobby Bonds). Virdon was forced to start Piniella in right.

That afternoon, the Orioles won yet another thriller, beating the Tigers by a single run. Back-up catcher, Andy Etchebarren doubled home the slow-footed Brooks Robinson all the way from first in the ninth inning.

It was snowing when starter Doc Medich arrived at County Stadium. Hours later, just over 4,000 people sat in the 37-degree cold to see if the Brewers could spoil the Yankees’ playoff hopes. The field was a mess. In the fourth inning, with Piniella on first, Thurman Munson doubled to right. Piniella should have scored easily but slipped in the mud rounding third. Both he and Munson were left stranded as the Brewers’ Kevin Kobel and Medich threw up zeros through the first six innings.

Meanwhile, at the Sheraton-Cadillac Hotel in Detroit, the Orioles coaches, a few players, and about a dozen reporters huddled in Earl Weaver’s room. Weaver had been nursing a cold for days but continued to smoke cigarette after cigarette. He had asked Milwaukee owner Bud Selig to place a phone next to a radio at County Stadium so that he could follow the action. With the receiver close to his ear, Weaver listened in, hunched-over and tense, providing a sketchy play-by-play for the rest of the room. When his voice became too hoarse to continue, Oriole trainer Ralph Salvon took a turn, followed by one of the day’s heroes, Brooks Robinson.

The Yankees scored twice in the top of the seventh inning. In the eighth, the Brewers had a man on third with one out when Don Money sliced a fly ball to right-center field. Piniella and Maddox moved after it. “The ball seemed to switch directions in the wind,” Piniella later recalled, “twist and turn and dance—damn that Earl Weaver—and nobody called for it.” Maddox could have reached the ball, but pulled up at the last moment. Piniella made a futile stab for it, but the ball landed behind him. Money scored the tying run on a sacrifice fly one batter later. Piniella got even with Weaver by smashing a water cooler.

Etchebarren relieved Robinson of play-by-play duties as the Yankee game moved into extra innings. Medich was still in the game, but the Brewers loaded the bases in the bottom of the tenth with one out for first baseman George Scott. “How many out, Andy?” asked Weaver, pacing anxiously. “One, skip, and the Boomer’s up.” A moment later Etchenbarren jumped up, dropped the phone, a broad grin on his face. “Base hit! A hit for the Boomer. We win. We win the division!” The coaches and players hugged and shook hands, then left for the bar. Weaver fell to his knees and banged the carpet with his fists. “You mean we don’t have to win tomorrow?” he said, his voice no louder than a whisper. “I don’t believe it.”

The Orioles had won 28 of their final 34 games. In the last 11 games of the season, they were 10-1, winning seven by a single run. Their 40 one-run wins tied a major league record they had set in 1970. “I was never happier to see a pennant race end,” Weaver later wrote. But after a valiant charge, the Orioles were depleted, and were quickly dispatched by the A’s in the playoffs.

Baltimore averaged 91 wins a season over the next four years but failed to make the playoffs. The Red Sox youth movement matured quickly, as Lynn and Rice led them to a World Series berth in 1975. For the rest of the decade, Boston’s rivalry with the Yankees featured an intensity not seen since the late 40s. For their part, once they returned to a newly restored Stadium in 1976, the Yankees hit their stride, winning three consecutive pennants and two championships.

But for the moment, they were despondent. After the 3-2 loss, Yankee broadcaster Phil Rizzuto was in tears as he recapped the game. “I had a good season,” Piniella told reporters after the game, “and loused it up on one play. My little boy could have caught that ball and he’s five-years old.”

The next day, before the final game of the regular season, Piniella received a telegram in the visitor’s locker room in Milwaukee. It was from Weaver.

“Thanks. I knew you’d screw it up someway.”

Over at Chicago Side, here’s Ira Berkow on Hank Sauer.

The Angels stacked? How ’bout them Blue Jays, who are close to finalizing a trade for the likable R.A. Dickey.

[Photo Via: Left Field Cards]

From our man Dayn Perry comes this gem:

Will there be a serenade of “Yoooouk” or a cascade of “boos” when Kevin Youkilis makes his Yankee Stadium debut in pinstripes? Judging by the initial response to the trade, the reaction might be somewhat mixed, especially with the Red Sox in town for Opening Day. Considering Youkilis’ infamous past as a Yankee killer, even those willing to welcome him into fold might still be susceptible to a flashback, particularly if they imbibed a little too much before the game.

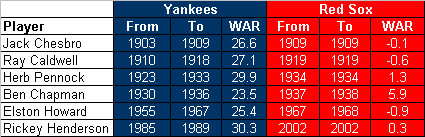

In the 112 year history of both organization, 219 players have appeared in at least one game for both the Yankees and the Red Sox. However, Youkilis migration to the Bronx isn’t a run of the mill rivalry crossover. With a bWAR of 29.5 while in Boston, the former All Star ranks 20th on the Red Sox all-time list for hitters. So, when Youkilis steps into the box on Opening Day, many in the crowd will likely do a double take, and not just because the third baseman will be without his signature facial hair.

Red Sox Standouts Who Became Yankees

Just missed: Duffy Lewis, who compiled 19.8 WAR with the Red Sox from 1910 to 1917, played for the Yankees from 1919 to 1920. Bill Monbouquette, who compiled 19.8 WAR with the Red Sox from 1958 to 1965, played for the Yankees from 1967 to 1968.

Note: Includes players who compiled 20 WAR or more with the Red Sox before joining the Yankees. Babe Ruth’s WAR includes totals as a pitcher and position player.

Source: Baseball-reference.com

By joining the Yankees, Youkilis becomes only the fifth Red Sox player to don the pinstripes after compiling at least 20 WAR in Boston. Babe Ruth was the first person to crossover, and since the Bambino helped build the Yankees into the most successful franchise in sports, the flow of talent between the two teams has usually benefited the Bronx Bombers. Although it would be almost 60 years before another Red Sox legend made his way to the Bronx, the two recent transfers since Luis Tiant’s short stint with the Yankees in 1979-1980 also had a major impact.

Like Youkilis, Wade Boggs was a mid-30s third baseman when he joined the Yankees after having a down year. However, Boggs rejuvenated his career in pinstripes, batting over .300 in four of five seasons to go along with an OPS+ of 112. Soon after Boggs departed the Bronx, Roger Clemens joined the Yankees. After the 1996 season, the Red Sox had also given up on the Rocket, claiming he was in the twilight of his career, but instead Clemens responded with two Cy Young seasons in Toronto. Following his stint with the Blue Jays, Clemens spent five years in pinstripes tormenting his former team by not only winning two World Series rings, but adding another Cy Young while on the “downside”.

Yankees Standouts Who Became Red Sox

Just missed: David Cone, who compiled 19.1 WAR with the Yankees from 1995 t0 2000, played for the Red Sox in 2001.

Note: Includes players who compiled 20 WAR or more with the Yankees before joining the Red Sox.

Source: Baseball-reference.com

The Red Sox have actually had more 20-plus WAR Yankees join their ranks than vice versa, but the contributions of those players were relatively insignificant. On offense, Ben Chapman, Elston Howard, and Rickey Henderson were all former All Stars in pinstripes who wound up playing for the Red Sox, but neither made much of an impact in Boston. Among pitchers, Jack Chesbro made his Hall of Fame bones with the Yankees, but ended his career by pitching six innings for the Red Sox. Herb Pennock, who actually had an undistinguished start to his career with the Athletics and Red Sox, was another successful pinstriped hurler who pitched his last season in Boston. Finally, Ray Caldwell cobbled together a competent 12 years with the Yankees, but also found his way to Boston before retiring as a Cleveland Indian.

Even if Yankee fans don’t warm up to him at first, Youkilis can still win their affection by making a contribution in line with the other former Red Sox who wound up wearing the pinstripes. Of course, if he struggles in the Bronx, the denizens of Yankee Stadium won’t hesitate to voice their displeasure. In that regard, however, Youkilis does have one distinct advantage. Even if the crowd showers him with “boos”, he can always pretend their singing his last name.

More Grown Man Gossip today at the Winter Meetings.

First, here’s a recap of yesterday’s dish.

And today’s big rumor.

Our man in the field, Chad Jennings has Yankee notes, here and here.

Or: Let’s make a dope deal.

First off, MLB Trade Rumors recaps Day One. Chad Jennings has the Yankee-related recap as well as a some lingering questions about Alex Rodriguez.

Let’s start today with this news on Curtis Granderson.

And then dig this from Emma: Yankee GM for a Day.

[Featured Image Via It’s a Long Season]

Friend asked me the other day, name any Met player who started and ended his career with the team.

“Ed Kranepool,” I said.

“That’s all I could come up with, too,” he said.

I’m sure there are others but not many, not ones with long careers. Which is one reason why the Mets showed David Wright the money.

[Photo Credit: Christopher Pasatieri/Getty Images]

Man, the Jays are getting easier to dislike by the minute (all they need to do is sign Jose Valverde, right?). Looks like they’re bringing back John Gibbons, a bona fide red ass, to manage the team next year.