“It bothers me to have been careless on some of these small details, especially when I was painstaking about most others…I trusted my notes and my memory on some smaller details, and there were obviously a few instances in which I didn’t have things quite right. That’s my fault, and I’ll take the blame…But if people are waiting for me to break down and confess that I made everything up, it’s not going to happen.”

—Matt McCarthy, USA Today

Mr. McCarthy has asserted that the Times has “crafted a chronology that simply doesn’t exist.” We did not create any chronology. The chronology already existed and we merely followed the chronology of the season that Mr. McCarthy claimed to be writing about. Obviously, some errors are endemic to publishing. No one understands that more than a daily newspaper such as ours. Rather, what we wrote about were events and quotations attributed to real people that could not possibly have taken place as Mr. McCarthy asserts. Given that many people to whom those events and quotes are ascribed are claiming that they didn’t happen, the examples that we found to be provably false lend credence to those concerns.

Alan Schwarz, New York Times

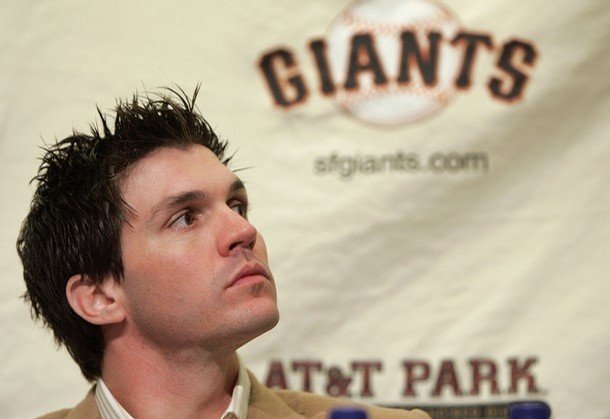

Last week, Benjamin Hill and Alan Schwarz wrote an article in the New York Times about Matt McCarthy’s recent memoir, Odd Man Out. The piece pointed out a series of factual errors made by McCarthy while calling into question the authenticy of the book. A second article lists the errors that the Times reporters found.

I read Odd Man Out and enjoyed it. I also interviewed McCarthy for this site. Needless to say, I was disturbed when I read the two articles in the Times.

If he was guilty of embellishing the truth or of flat-out lying, I reasoned, McCarthy deserved condemnation. That said, I was struck by how forcefully the Times went after McCarthy. I thought it was a stretch on their part to associate McCarthy with James Frey, infamous for his memoir fraud in A Million Little Pieces. Many of errors that were listed seemed innocuous to me, and suggested sloppiness on the part of McCarthy and Viking, his publisher. I didn’t find anything malicious behind it. On the other hand, the sheer amount of mistakes the Times brought to light was troubling. They had McCarthy placing people in places where they were not, having conversations that could not have occured, at least not as how they have been presented in the book.

I don’t think McCarthy was trying to be lurid necessarily, but the accumulation of so many errors led me to question his authority as a writer. I was left wondering, “What was really true?” Whether McCarthy was being naive or arrogant, I can’t say. But his carelessness, as reported by the Times, did not reflect well on either him or the book.

As a writer, my greatest concern is how this could potentially make things more difficult on the rest of us, simply by creating a standard of excellence that can’t be met without stretching the truth.

McCarthy toured the country promoting the book last week. He first responded to the Times’ articles in this piece for the USA Today. Here is one TV interview McCarthy did later in the week, and another.

I conducted a second Q&A with McCarthy via e-mail this week, and I also spoke to Alan Schwarz. McCarthy has been amiable and professional with me. I know other journalists in the industry who think highly of him. I also know he’s in the business of promoting his book. I’ve known Schwarz for several years and think he is a first-class reporter, as well as an exceedingly ethical and even-handed journalist.

I will leave it to you to decide what to make of this fine mess.

BB: Your book has achieved a good deal of early success, but that was marred last week by the New York Times article which reported many inaccuracies in your story.

MM: I stand by the contents of Odd Man Out. The journals I kept were very specific and extremely detailed with regards to dialogue. I was a ballplayer keeping a journal, not David Halberstam, and so I made several mistakes in chronology. But I can say this with absolute certainty: not a single one of them changes the tone or meaning of my story, or makes me doubt the truth of the experience as I wrote it down in the book. The lies James Frey and Herman Rosenblat told were fundamental to and pervasive in their narratives – to compare that with a mix-up here and there in dates in Odd Man Out, which has no true effect on the book’s nature, is at best grossly unfair and at worst sensationalistic on the part of a newspaper.

BB: So do you believe this is an unfair attack on the part of the Times?

MM: It appears to me that Benjamin Hill and Alan Schwarz in the New York Times story are writing a partisan article and acting as advocates for Tom Kotchman et al., and using their lawyer’s letter as gospel truth and accepting their statements as fact. I find it interesting that Benjamin Hill and Alan Schwartz have constructed a detailed chronology of dates, which is 90% of their “error’ argument, when in Odd Man Out I do not use dates. I use only general references (a day later, two weeks earlier). Many of their claims to so called “errors” in the book have been created because Hill and Schwarz assign dates to events that I did not assign dates to. Each of the players and former players quoted in the New York Times piece are naturally nit-picking at minor details since they are not represented in a positive light. They are not going after the fundamental truths in Odd Man Out.

BB: I understand that you didn’t use dates, but since you are writing about a specific season it is easy enough to re-construct one. Why do you think the Times would want to pick on you?

MM: I don’t know if I should be the one to speculate about why the Times wrote their article. But I encourage your readers to check out my book and read the Times article and decide for themselves. I’ve received an overwhelmingly positive response from people who have read both.

BB: You mentioned that you were a ball player keeping journals and not David Halberstam. Still, you were writing a book for publication, and I’m sure that Halberstam, too, needed someone to double-check his reporting at times… Can you understand how people might feel that if the facts that can be checked don’t check out how it throws the rest of the material into doubt, lending credence to the criticisms by Kotchman, etc?

MM: My book contains tens of thousands of details that I recounted from journals I kept. For example, from pages 102-104 I recount my performance against the Ogden Raptors inning by inning (and pitch by pitch in some cases) and it was all accurate down to the type of pitch I was throwing. At one point I write that Manuel Melo popped out to end the inning when it turns out someone else popped out to end the inning. In no way does this oversight change anything material about the book.

BB: Based on the kinds of errors you admit to, why should readers not question the veracity of the remainder of the book?

MM: I have acknowledged several errors related to box scores and chronology. Not a single one of them changes the tone or meaning of my story.

BB: The Times pointed out dozens of errors in their piece. Were they in fact correct on the amount of errors?

MM: No. Numerous situations were taken out of context. Is it an error for me to write “Breslow had something like 9 scoreless innings” when in fact he had 12 scoreless innings? They also consider it an error for me to quote Jon Steitz as saying, “I’ve pitched in 11 games and lost all of them,” despite the fact that he went 0-11 that season. They say it’s an error for me to say Joe Saunders “made batters look silly” because he gave up four runs in a game even though batters were swinging at balls over their heads and in the dirt.

BB: I think it is understandable that you could make some of these errors. However, the more puzzling ones include the incident on Larry King night where a person is placed at a scene where, as the Times claims, he was not. Was the Times correct in pointing out this mistake? And if so, do you see how that could effectively undermine your credibility as an author?

MM: Regarding Larry King Night: I said that King’s kid went around punching a bunch of my teammates in the groin and I mistakenly included Matt Brown in this list. I regret including him in the list, but it doesn’t change the fact that King’s kids were in the clubhouse before the game wreaking havoc on our midsections.

BB: I thought the suggestion that your book was like A Million Little Pieces was a stretch. Still, while a fraud, Fray was writing about himself, while you are being accused of hurting other people’s reputations. Do you regret any misleading characterizations that were the result of an error on your part?

MM: No. This book wasn’t about the box scores. It was about brining people closer to the game and I’ve received countless emails from fans who now feel closer to the game. It’s a great feeling.

BB: Have you had any direct contact with the authors of the Times piece since it appeared?

MM: No. I offered to correct the errors they have attributed to me and the errors that appear in their own article, but they said it wasn’t necessary…

BB: Who at the Times did you contact to correct the errors? Did they give any reason why it wasn’t necessary?

MM: I created a point by point rebuttal and gave it to the head of publicity at Viking who was in frequent contact with the Times authors. She offered them my rebuttal but they said they were going ahead with their story and didn’t need my side.

BB: How did the writing process work with your publisher?

MM: I worked closely with my editor on the organization and the overall tone and message of the book and it went through copy-editing and was vetted by legal.

BB: Looking back on it now, would you have used a fact-checker? Or do you feel that the mistakes that have been publicized are essentially innocuous?

MM: I suppose the simple answer is that I would’ve used a fact-checker.

BB: SI ran an excerpt from the book. What involvement, if any, did they have with the publication of the book?

MM: SI read an early draft of the manuscript and requested the opportunity to excerpt a portion.

BB: I know you faced some criticism even before the Times article came out last week. An Angels blogger left a comment in the thread for our original interview. Still, what was your initial reaction when you read the article in the Times?

MM: There have been a wide range of responses to the book and at some level you prepare yourself for anything.

BB: But how did it make you feel? Angry? Do you feel that in essence, the Times’ article is making legitimate criticisms or do you feel that it is an unfair attack?

MM: You’re upset any time someone takes things out of context, but that’s to be expected and there’s nothing you can do about it but defend your work.

BB: You say that you stand by your book. Would you have changed anything in your process knowing what you do now? What has this taught you?

MM: In hindsight it would have been nice to have gone through the box scores from the 350 to 400 high school, college, and minor league games that I played in.

BB: I read that Viking is considering putting out a revised version of the book. Doesn’t that suggest that they are unhappy with the book, or that they could be facing a lawsuit?

MM: Viking was misquoted in the USA Today article when it says, “McCarthy’s publisher, Viking, said it’s likely a revised version of the book will be released…” There are no plans for a revised version at this time.

BB: How has this controversy impacted sales?

MM: Sales have remained strong- last week the book was number 21 on the New York Times Best Seller List.

* * * *

I contacted Schwarz to get his take on some of McCarthy’s responses. I have set up Schwarz’s answers in paragraph form for easier reading.

Mr. McCarthy’s claims that he was denied an opportunity to, in his words, ‘rebut’ his own errors are not only preposterous but adds to his growing list of outright falsehoods. Our interview spanned more than an hour and was comprised mostly of my describing to him every substantive error — sometimes literally showing him things like transaction logs that proved he had the wrong person involved in some distasteful scene, and a copy of his own original contract that proved one quote-laden episode with Tony Reagins to be completely fabricated — and explaining its relevance to the larger picture. He offered explanations for each of them (and I put the most relevant ones in the article so that his side was fairly represented). This went on for probably 10 or 12 of the most substantial errors, with my explaining at every juncture that, while some were clearly not that big of a deal, they called into question the veracity of many other, less provably false scenes that real people said had not happened as he described.

I said that I would be happy to quote portions of the journals he said corrorborated what he had written in the book; he declined to let me do so. I asked to speak with the teammates he claimed supported him; he declined to say who they were.

At the end of the interview, I asked Mr. McCarthy if there was anything he wanted to add, anything that was important given what the story was going to be about. He thought for a moment and said no. I then told him that if he realized there was anything he wanted to add or clarify, that he had my cell phone number and I would be available to him all day for as long as he wanted. He said OK. I have not heard from him since.

The only person I did hear from, in mid-afternoon, was a call back from the Viking publicist. She said that Matt had given her explanations for each error, and would I like to hear them? I said that, to be honest, I had already gone over the errors with Matt in great detail, and that the purpose of my call was to provide opportunity for Viking to comment itself on the situation, its vetting procedures, et cetera. With no objection or hesitation she continued the interview, answering a few questions and offering a few comments — the relevant ones of which I put in the article. She asked if I had talked to Craig Breslow to seek corroboration of McCarthy’s version of events; I explained that Mr. Breslow, McCarthy’s best friend from Yale, was not on the Provo team and could not possibly speak to what happened in 90 percent of the stories told in the book. I mentioned that I had asked McCarthy for the names of the Provo teammates he said supported him so that I could call them, and that he had declined. At the end, knowing that the story was running that evening, the Viking publicist said she wanted to check with Matt on some things and she would call me back. She never did, which is of course her prerogative.

Mr. McCarthy is now saying that the New York Times told him about his list of rebuttals, and I am quoting him here, “We don’t want to hear it. We’re running our story.” Once again, he is putting words into people’s mouths that are blatantly untrue only to further his distorted (and false) image of reality.

And once again, he has done so forgetting that there is 100 percent proof of his dishonesty — in the form of my recording of his interview and a transcript of my conversation with Viking, which I can make available to any interested party. Last I checked, he still has my number.