Head on over to SB Nation and check out a memoir story I wrote about my father and the two Rogers–Angell and Kahn. Leave a comment over there if you dig it.

Thanks.

Head on over to SB Nation and check out a memoir story I wrote about my father and the two Rogers–Angell and Kahn. Leave a comment over there if you dig it.

Thanks.

Three dingers off three pitches in different spots. The first one reminded me of George Brett vs. Goose Gossage. Sandoval didn’t hit a rainmaker but goddamn, turn on the high cheese from Verlander? You could retire on a homer like that. Then to hit two more?

Daaaaaaaamn.

[Photo Credit: Jason O. Watson/Getty Images]

Game One gives Justin Verlander’s filth vs. Barry Zito’s 85 mph cheeseburgers. Tigers should be hungry and they’ve got some big ol’ cheeseburger eating fat bastards on their squad. Wonder if the time off will hurt them like it did in 2006.

Have at it you guys.

Let’s Go Base-ball.

Head on over to SB Nation’s Longform and check out this beautiful piece of work by Michael Graff.

His legs once made him great. Every bull rider knows that the key to riding an animal whose sole purpose is to toss you straight to cowboy heaven is this: balance. And the key to balance is keeping your knees as close together as possible. But if you wobble, if you lose your balance, the emergency plan is to spur – to take the star on the heel of your boot, dig it into the thick hide, and hang on for your riding life with your legs.

Jerome Davis was able to do both simultaneously. He could keep his knees close together, almost tight enough to squeeze a soccer ball in between them, while pointing his toes directly sideways.

“It’s the weirdest shit I’ve ever seen,” says J.B. Mauney, one of the top bull riders in the world today. “I can’t even do it standing on the ground.”

[Photo Via: SB Nation]

Over at Sports on Earth Jack Dickey catches up with Gary Sheffield.

Here’s Pat Jordan’s 1971 Sports Illustrated pool room story, “A Clutch of Odd Birds”:

Joe McNeill’s mother used to say, there’s a Mort Berger in every town, and she may have been right. But those of us who knew him in the summer of 1962 liked to think she was wrong and secretly hoped he was unique. Berger was the proprietor of the only pool hall I can ever remember seeing in our small town in Fairfield County, Conn. He was a Jew from South Philadelphia who spoke out of the side of his mouth. On windy days he stuck bobby pins in his hair, which was deep reddish brown, the color of an Irish setter’s. But, at 33, he didn’t have much to stick bobby pins in. To compensate, Berger let the little patch of hair at the base of his neck grow until it would reach far down his back if he let it—which he didn’t. Instead, he combed it forward over his brow where he teased it into a tuft like a rooster’s comb. Actually, Berger resembled a rooster more than anything. He had watery blue eyes, a pointy nose and the gently curving, bottom-heavy build of a Rhode Island Red. He waddled.

Berger’s greatest fear was that a strong wind might come along and reveal his artifice. To defend against this possibility he ventured outside the pool hall as infrequently as possible. This tended to make his pale and mottled redhead’s skin so opaque that veins were visible beneath it. Whenever he did appear outside he walked about with his hand flattened over the top of his head like a man who had misplaced a migraine. Finally, in desperation, he had resorted to bobby pins. It was hard for anyone, at first, to talk casually to Berger without breaking up at the sight of the bobby pins, but after a few withering looks one learned to ignore them. The only person I ever heard question Berger about them was a college freshman who wandered into the pool hall one day, challenged Jack the Rat to a game of dollar nine ball and then, pointing to Berger’s hair, asked, “How come you got bobby pins in your head?” The place fell mute. It seemed even the skidding billiard balls froze in midflight. Berger’s face took on the color of his tuft. He fixed a beady-eyed stare on the offender and said in a voice the recollection of which still sends shivers down my spine, “You, my friend, are banished for life.” The humiliation! Worse even than Kant’s categorical imperative! It would have been better for the boob if Berger, yarmulke over his tuft, prayer shawl about his shoulders, had intoned the Hebrew prayers for the dead.

And for more on pool, here’s another gem from Patty, written twenty-four years later, “The Magician”:

At midnight on a bitterly cold January 15 the lobby of the Executive West Hotel near the Louisville, Kentucky, airport was crowded with men and a few women, all waiting anxiously for the guest of honor.

A man in a yellow windbreaker came through the front door and walked toward the registration desk. A murmur rose from the crowd. Everyone stared at him, a small brown man with slitlike eyes, a wispy Fu Manchu moustache, and no front teeth. He wore a soiled T-shirt and wrinkled, baggy jeans. He moved hunched over, his eyes lowered.

People clustered around him. Men flipped open their cell phones and called their friends to say “He’s here!” They introduced him to their girlfriends. The man looked embarrassed. Another man thrust his cell phone at him and said, “Please say hello to my son; he’s been waiting up all night.” The small man mumbled a few words in broken English. Then the hotel clerk asked him his name. He said, “Reyes.” Someone called out, “Just put down ‘the Magician.'”

Efren Reyes, fifty, was born in poverty, the fifth of nine children, in a dusty little town in the Philippines without electricity or running water. When he was five, his parents sent him to live with his uncle, who owned a pool hall in Manila. Efren cleaned up the pool hall and watched. He was fascinated by the way the players made the balls move around the table and fall into pockets—and by the way money changed hands after a game. At night he slept on a pool table and dreamed of combinations. He had mastered the game in his head before he finally picked up a pool cue, at the age of eight. He stood on a pile of Coke crates to shoot, two hours in the morning and two hours at night. At nine he played his first money game, and at twelve he won $100; he sent $90 home to his family. Soon he was the best pool shooter in Manila. His friends would wait for him in the pool hall after school, hand him his cue when he walked in the door, and back him in gambling games. He was the best pool shooter in the Philippines when he quit school, at fifteen. By the time he was in his twenties, no one in the Philippines would play him any longer, so he toured Asia. He wrote down in a notebook the names of the best pool shooters in the world, and proceeded to beat them one by one. He became a legend. People who had seen him play recounted the impossible shots he had made. They called him a genius, the greatest pool shooter who had ever lived. Even people who had never seen him play, including many in the United States, soon heard the legend of Efren Reyes, “the Magician.”

[Photo Credit: Adam Bartos]

What’s worse? The Yanks getting swept by the Tigers or the Cardinals blowing a 3-1 lead to the Giants?

Discuss.

[Photo Credit: Ezra Shaw/Getty Images via It’s a Long Season]

NLCS Game Seven. The home team has the momentum but I have a feeling that the Cards will break their hearts tonight.

Have at it, you guys.

Let’s Go Base-ball!

[Photo Via: Bonus Baseball]

Nice story on Phil Coke’s less than glamorous rise to the top by Jonah Keri over at Grantland.

[Photo Via: A Continuous Lean]

Giants are up against it tonight with Barry Zito on the hill…gasp.

Cards one game from the Whirled Serious.

Let’s Go Base-ball!

[Photo Via: This Isn’t Happiness]

Giants, Cards: NLCS Game 3.

We’ll have the lineup once it’s posted.

Go Baseball.

[Image by Matt Duffin]

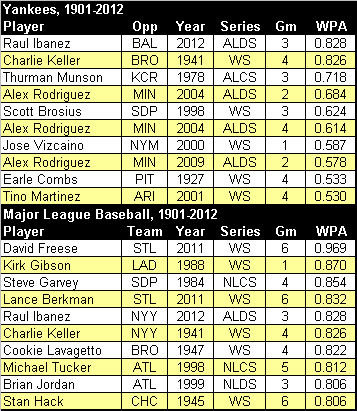

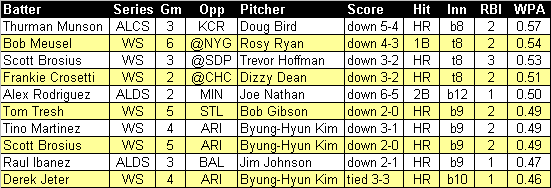

Raul Ibanez spent the regular season compiling big hits, but he saved his most spectacular heroics for October. Now, he stands among the Yankees’ legion of immortals as one of the most clutch performers in the franchise’s postseason history.

The Yankees have had no shortage of October heroes, but with two mighty blows, Ibanez thrust his name to the top of the list. By homering to tie the game in the ninth and then following up with a walk-off encore in the 12th inning, Ibanez racked up the highest cumulative Win Probability Added (WPA) in the team’s postseason history, surpassing Charlie Keller’s clutch hitting in game four of the 1941 World Series. In addition, Ibanez’ epic performance also cracked the top-five for all of baseball, and made the 40-year old slugger the first player to hit a homerun in both the ninth inning and extra innings of the same postseason game.

Top-10 Postseason WPA, Yankees and MLB

Source: Baseball-reference.com

In addition to rescuing the Yankees from a pivotal game-three defeat, Ibanez also saved Joe Girardi from having to face intense scrutiny for using him as a pinch hitter for Alex Rodriguez. In addition, Arod was able to spend the post game magnanimously applauding his teammate instead of having to answer unfair questions about his perceived inability to produce in the postseason. Of course, the irony is that if there was one man in the clubhouse who knew exactly how Ibanez felt, it was Rodriguez.

Before Ibanez’ game-tying homerun in the ninth inning, the last hitter to erase a postseason deficit in his team’s final turn was, you guessed it, Alex Rodriguez. In 2009, Arod actually accomplished the rare feat on two occasions: the first against Joe Nathan in game two of the ALDS and the second against Brian Fuentes in game two of the ALCS. Only 32 postseason home runs have helped a team tie or take the lead when trailing in the ninth inning or later, and Johnny Bench and Arod are the only players to do it twice.

Yankees’ Top-10 Postseason Hits, by WPA

Source: Baseball-reference.com

It amusing to note that Rodriguez has compiled three of the top-10 WPA ratings in the Yankees long and illustrious postseason history (he also owns the highest WPA in the franchise’s regular season history). Although his struggles in the current ALDS are undeniable, the relentless characterization of Arod as an unclutch performer remains one of the great mysteries of irrational fandom. Fortunately, Joe Girardi isn’t as fickle as far too many Yankee fans. If he was, Raul Ibanez, who batted .057 in 60 plate appearances over a 24-game span at the end of the season, probably wouldn’t even be on the postseason roster. That’s something to think about the next time you feel the urge to overreact to a small sample.

This afternoon we’ve got two NL games: Cards at Nats and then Giants at Cincy.

Enjoy.

[Photo Credit: Saint Anslem]

Chad Jennings with some Yankee notes. At ESPN/New York, Mark Simon looks at Baltimore’s Miguel Gonzalez.

And over at Deadspin, here’s Tom Scocca on Ichiro’s play at the plate last night.

Tonight gives a pair of Game 3’s: Giants vs. the Reds and later tonight, Tigers vs. the A’s.

Have at it.

Let’s Go Base-ball!

[Photo Via: Omynameistaken]

Over at SBN’s Longform, check out this fine piece story by William Browning:

Before the boy passed 10 his parents left the Mississippi Delta for the pine woods farther south, where his mother found a teaching job in the county. They were a young family, renting near the school, when his father left.

The boy felt lost in that new place. To better hide the hurt he whittled away his footprints through the years, turning his back on basketball, the drum line, a job bagging groceries and a place on the school honor roll. When he handed in his football jersey during his junior year there was nothing else to quit. He did it in spring, a few months after the ’96 season. A slow-footed receiver four notches down the depth chart, he thought he would not be missed. He was surprised when the coach sent a note to his English teacher asking to see him. Everyone called him, “Coach.” He was humorless and had a dry voice. He growled through one-sided conversations on the football field but off it he could be inarticulate.

The boy remembers walking the hallway toward his office, telling himself not to give in. He sat face-to-face with Coach, Bear Bryant’s picture hanging nearby on the office wall. Are you sure you want to spend your senior year in the bleachers? Coach said. Full of teenage arrogance, the boy said he wouldn’t be attending any games. He said he had watched from the sideline for two seasons and had his fill.

Coach, always slow to speak, leaned back in his chair and warned him. He warned him that not that season, but in a decade or so, he would come to regret his decision and that once made, it could not be undone.

The boy laughed. A grown man, said the boy, has no business thinking of games he did or did not play in high school. Coach said all right and the boy left. He never called him “Coach” again. Not because he walked away from football, but because that summer the coach married his mother.

And the boy hated him for that.

[Photo Credit: Colorado Springs Gazette ]

Over at Grantland, here’s Bryan Curtis on Josh Hamilton:

By now, you and I could recite the outlines of The Story: Hamilton, baseball’s no. 1 overall draft pick in 1999, falls under the sway of crack and cocaine; abandons his wife and daughters; gets clean; gets acquainted with God; and in a semi-damaged, heavily tattooed state, leads Texas to the franchise’s first two World Series appearances.

While Texas fans still love Hamilton’s “story of redemption,” ESPN’s Jean-Jacques Taylor noted the other day, Hamilton “has abused that goodwill.” Not by having a bad season: Hamilton hit 43 homers, just one fewer than Miguel Cabrera, and posted a .930 OPS. No, Hamilton abused it by hitting into a first-pitch double-play ball against the Orioles and looking at just eight pitches in four at-bats and, with a frequency that seemed to accelerate when the Rangers needed it least, behaving like a flake.

Before we dive into how Texas fell out of love with Josh Hamilton, I want to be clear that I’m not making fun of Hamilton’s religion. I’m not questioning the events of The Story. What I’m suggesting is that Hamilton has become a prisoner of it.

…It’s not defending Josh Hamilton to say that he became despised this year for many of the things that, in the confines of a redemption narrative, once made him beloved. The Story swallowed the man. Hamilton seems like a reasonably friendly, occasionally defensive guy who is teetering on the edge of sobriety, who is prone to inconvenient bouts of detachment, and who gets hurt a lot. When he goes to his next team, I hope a new story will start there. But I have a sinking feeling that every time he loses a fly ball, Hamilton will again be a prisoner of redemption, trapped in a tale too flawless for any man.