The good folks at Deadspin have this excerpt from Frank Deford’s new memoir. It concerns Granny Rice.

Have at it.

The good folks at Deadspin have this excerpt from Frank Deford’s new memoir. It concerns Granny Rice.

Have at it.

A walk is as good as a hit. Even though some traditionalists might view such a statement as sabermetric hokum, that sentiment has been expressed by coaches from little league to the majors for who knows how many years. Of course, that doesn’t necessarily make it true. In many cases, a hit is much more valuable than a base on balls, but in terms of preserving precious outs, both are equally effective.

With the Rays in town, it’s the perfect time to examine the relationship between batting average and on-base percentage. Over the first two games of the current series at Yankee Stadium, the first two hitters in the Tampa lineup have been Ben Zobrist and Carlos Pena, whose relatively low batting averages make them seem like an unlikely pair to feature in the first two slots. Leave it to Joe Maddon to think outside the box, but, in this instance, his strategy isn’t very unorthodox. You see, Zobrist and Pena have two of the highest on-base percentages on the team.

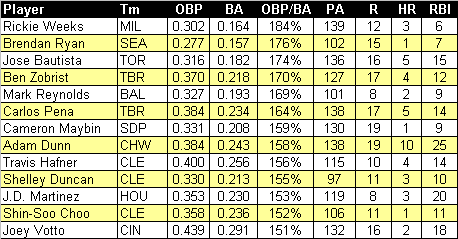

Having a high on-base percentage despite a low batting average isn’t very common, but in Zobrist and Pena, the Rays have two of the top three hitters in terms of the differential between both rates (Zobrist is first at .152 and Pena is third at .150; Dodgers’ AJ Ellis is second at .151). Both hitters also rank among only 13 qualified batters who currently have an on-base percentage at least 150% greater than their batting average, so teams facing the Rays might be lulled into a false sense of security if they only focus on the latter.

Hitters with OBP to BA Ratios of At Least 150%, Qualified Batters in 2012

Source: Baseball-reference.com

With an on-base percentage that is 184% of his batting average, Brewers’ second baseman Rickie Weeks has managed to salvage some value from the disappointingly slow start to his 2012 season. Like most of the members of the list above, his high ratio is mostly the result of having a subpar batting average. However, there is one standout. Reds’ All Star first baseman Joey Votto has piggybacked on a very respectable batting average of .291 with an on-base percentage that ranks fifth in the National League, which is par for the course for the former MVP, whose career ratio is 130% (.406 OBP vs. 312 BA).

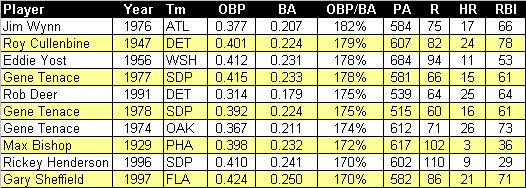

If Weeks maintains his current rates, he’d break the current on-base versus batting average differential record of 182% (based on qualified seasons), which was set by Braves’ outfielder Jimmy Wynn in 1976. That season, the Toy Cannon only hit .207, but, thanks to a league leading 127 walks, still finished in the top-10 in on-base percentage. In total, 175 players have had a qualified season with an OBP/BA ratio of at least 150%, but none has been more impressive than Barry Bonds’ 2004 campaign. That season, the homerun champion won the batting title with a .362 average and still managed to post a high multiple by reaching base in a remarkable 61% of all plate appearances.

10 Highest OBP to BA Ratios, Qualified Seasons since 1901

Source: Baseball-reference.com

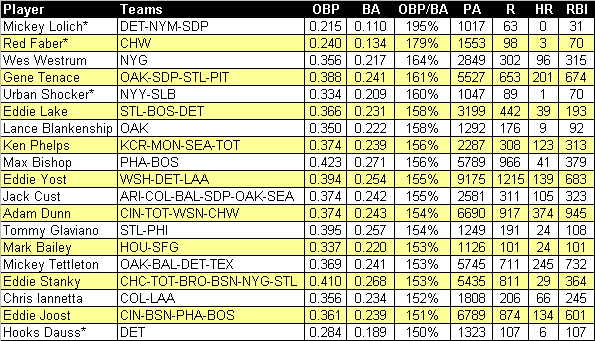

It’s hard enough for a hitter to reach base at a high multiple to his batting average in a single season, much less for an entire career. However, 19 players with at least 1,000 plate appearances have managed to turn the trick, and chief among them was Mickey Lolich. In his 16 major league seasons, which spanned the advent of the DH rule, the former Tigers, Mets, and Padres pitcher ended his batting career with more walks than base hits (105 to 90). As a result, Lolich’s on-base percentage was nearly double his batting average, a discrepancy that easily ranks as the widest in baseball history.

Hitters with Career OBP to BA Ratios of At Least 150%, 1901

*Indicates pitchers.

Note: Based on a minimum of 1,000 plate appearances.

Source: Baseball-reference.com

Among position players, West Westrum’s 164% multiple ranks as the largest differential, but the most impressive divergence probably belongs to Gene Tenace, whose on-base percentage was 161% higher than his batting average in over 5,500 plate appearances. Tenace, a catcher/first baseman whom some regard as a borderline Hall of Famer, ended his career with a very impressive OPS+ of 136, making him a prime example of a hitter capable of providing significant value over and beyond his relatively low batting average.

What about the other end of the spectrum? For a look at those hitters whose ability to reach base rests solely on their bats, join me for a companion piece over at the Captain’s Blog.

Andy Pettitte is on his way but he’s not what the Yanks need writes Tyler Kepner in the Times:

Rays Manager Joe Maddon credited Ron Porterfield, the team’s head athletic trainer, for his pitchers’ durability, but Hellickson said he assumed all teams had the same kind of programs. Cashman said the pressure of New York makes the comparison unfair.

“I know they have a lot younger guys, but Pineda’s young and he just went down,” Cashman said. “I know the innings here are more stressful than the innings there, no doubt about that. Throwing 100 pitches in New York versus 100 pitches in Tampa are two different stresses. The stress level’s radically different on each pitch.”

Maddon said Cashman’s theory was worth considering. In a cosmic way, he could have added, the Rays deserve a benefit from playing before small crowds in an outdated home ballpark. In any case, Maddon said, the starters are essential to their model.

“Without that pitching, all the other wonderful stuff that we are, I don’t think really works nearly as effectively,” Maddon said. “It all starts with the starting pitching. That particular group and that part of our team really permits us to do all the other things well.”

While you are there, check out Hunter Atkins’s story about Joe Maddon–the King of Shifts.

[Photo Via Rays Renegade]

[Drawing of the Dominican Dandy posted at Josh Powell’s tumblr site; found via Pitchers n Poets]

Steve Kerr advocates raising the NBA’s age limit over at Grantland. His argument is that the NBA is better served financially by having players in college longer. And in the end, Steve, isn’t what’s in the best financial interests of the NBA really what’s best for America?

The dreckiest sentence in this mountain of dreck is this one: “Why should NBA franchises assume the responsibility and financial burden of player development when, once upon a time, colleges happily assumed that role for them?”

Let’s rewrite that question for Steve, but add one single ounce of humanity and perspective: “Why should anyone other than the NBA assume the responsibility and financial burden of player development?” Steve thinks the NBA is entitled to reap the corrupted benefits of the professional basketball player factory that is the NCAA.

And thank goodness for the NCAA. Assuming responsibilty over here and financial burden over there, all out of the goodness of their collective heart. The NCAA and NBA have concocted a virtually risk-free scam in which the NCAA develops talent at no cost, funnels that talent into a monopoly. The only potential risk is a player getting hurt before he gets pushed through the funnel. That’s a minimal risk because the flow of talent is endless.

Well, minimal risk for the NBA and NCAA anyway. But screw the kid. That’s Kerr’s point and at least he had the guts to state it bluntly – albeit after he piled on about 2000 words of tone-deaf platitudes and other compost:

The arguments against raising the age requirement hinge on civil liberties, points like, “Who are we to deny a 19-year-old kid a chance to make a living when he can vote, drive, and fight in a war?” If this were about legality or fairness, you might have a case. But it’s really about business. The National Basketball Association is a multi-billion-dollar industry that depends on ticket sales, sponsorships, corporate dollars, and media contracts to operate successfully. If the league believes one rule tweak — whatever it is — would improve its product and make it more efficient, then it should be allowed to make that business decision.

With that guiding principle Steve, what other “rule tweaks” might serve the greater good of the NBA, and by definition, America? An endless and frightening list of things comes to mind. No business should be allowed to violate fundamental freedoms of our society to improve their bottom line. That type of thinking is vile.

And why is Grantland publishing this badifesto? I’m not asking an entire collection of writers to speak with one voice, but dropping in a non-writer with partisan ties to an issue to editoriolize is in poor taste. Especially when his case is so glaringly weak and offered without counterpoint.

I also don’t think rich, old, White men should be allowed to arbitrarly decide when impoverished, young, Black adults should be allowed to earn a living in their chosen profession, but Steve Kerr deftly dealt with that issue by not mentioning it.

Over at Grantland, Jonathan Abrams has a piece on the divergent careers of Tyson Chandler and Eddy Curry.

[Photo Credit: Williams and Hirakawa for SLAM]

Hoops documentary directed by Adam Yauch.

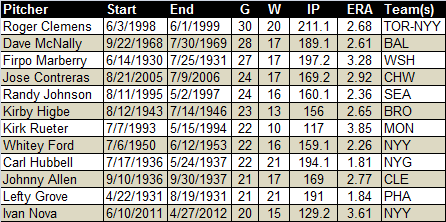

Ivan Nova’s luck finally ran out. For the first time since June 3, 2011, the Yankees’ right hander was tagged with a loss, snapping a streak of 15 straight victories, which ranks as the 17th longest stretch since 1918. Because of the outcome, Nova’s streak of 20 games without a loss also game to an end, leaving him two behind Whitey Ford for the franchise record (Roger Clemens’ stretch of 30 games with the Blue Jays and Yankees from 1998 to 1999 is the all-time record).

Longest Streaks Without a Loss by a Starter, Since 1918

Note: 12 other pitchers are tied with Nova at 20.

Source: Baseball-reference.com

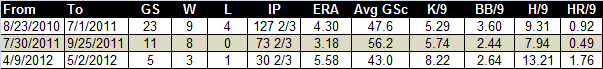

In fairness to Nova, his streak wasn’t all about luck. During the 20 games in which he went without a loss, the righty posted a respectable ERA of 3.61 to go along with an average Game Score of 53.7. However, those figures usually don’t add up to such a long winning streak. Of course, that’s because one very important statistic has been left out of the equation. During Nova’s streak, the Yankees offense scored 139 runs, or nearly seven per game. As a result, Nova was able to avoid being saddled with a loss in nine games in which his Game Score was below 50, including two that were below 25.

Just like his winning streak, Ivan Nova’s early career has been a contradiction. In his first 23 starts, the right hander posted an impressive 9-4 record, but it was supported by very questionable peripherals. However, after returning from a mid-season demotion, Nova was a very different pitcher. Thanks to an increased use of his slider, the 24 year-old bolstered his Rookie of the Year credentials by not only going 8-0, but doing so with much more impressive underlying statistics.

Over the first five games of 2012, Nova’s development has seemingly taken two different tracks. On the one hand, he has continued to improve his strikeout and walk rates, which should bode well for overall performance. However, those trends have come at a price because the right hander has also experienced a very significant spike in the number of hits and home runs allowed. To this point, the negatives have outweighed the positives, at least based upon Nova’s ERA and average Game Score.

A Tale of Three Pitchers: A Segmented Look at Nova’s Career

Source: Baseball-reference.com

So, what are we to make of Nova? On the one hand, his improved ability to generate strikeouts and avoid issuing free passes seems very promising. Considering his astoundingly high BABIP (batting average on balls in play) of .398, it also seems as if Nova has been the victim of bad luck (and perhaps bad defense). At least that’s what measures like xFIP suggest. According to that metric, which takes into account peripherals as well as a normalized HR rate to predict a pitcher’s future performance, Nova’s inflated ERA of 5.58 should be more like 3.83. The Yankees would probably sign up for that without a second thought.

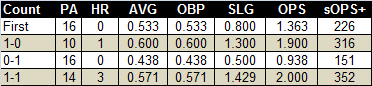

But, can we just dismiss all of the hits and homers that Nova has surrendered? Although his BABIP is abnormally high, it’s worth noting that the number of line drives and fly balls hit off Nova have increased (from 47.3% combined in 2011 to 55.8% in 2012), which might explain why he has allowed so many more extra base hits. However, that doesn’t explain why he has transformed from a groundball pitcher to one who allows so many batted balls to be hit in the air. One possible answer could be that Nova is throwing too many strikes, particularly early in the count. Although that theory is supported by the high OPS against Nova in first pitch, 0-1, 1-0, and 1-1 counts, a sample of only five starts makes it far from conclusive.

Ivan Nova’s Performance in Various Counts, 2012

Note: sOPS+ compares a split to the adjusted average for the league. A reading above 100 for a pitcher is considered below average.

Source: Baseball-reference.com

Who is the real Ivan Nova and what role has luck played in his early career? His success has seemed to be a byproduct of good fortune, while his struggles appear rooted in bad luck, making it impossible to get a good handle on exactly what kind of pitcher he has been, not to mention will be. So, despite his impressive winning percentage, Nova remains one of the many question marks in the Yankees’ rotation, which, this year, hasn’t been lucky or good. At this point, I’ll settle for either.

Gatti-Ward, Virginia Woolf? It’s all there in this intriguing piece by Sergio De La Pava over at Triple Canopy.

[Photograph By Devin Yalkin]

According to this report, Junior Seau is dead at 43. Police are investigating this case as an apparent suicide.

My God, this is sad.

[Photo Credit: Sasha Kurmaz]

Head on over to Grantland for a long appreciation of the Chipmunks by Bryan Curtis. Nice to see Shecter, Merchant, Isaacs, Vecsey and company celebrated.

The only problem I have with the piece is how Jimmy Cannon is portrayed. It’s not that Curtis is inaccurate in saying that Cannon was tired and bitter by the mid-’60s, or that he was the foil that the Chipmunks needed (too bad there is no mention of Dick Young). Curtis lampoons Cannon’s writing style but I wish it was balanced with a sense of how good Cannon was in his prime. Cannon is seen here as he’s most often remembered these days–an out-of-touch old timer who had become a parody of himself. That’s a shame because while Cannon was sentimental to a fault when he was bad, he was terrific, one of the very best, when he was good.

[Picture by Bags]

I saw a security guard in my office building this morning. Knicks fan.

“You heard about Amare?” I said.

He looked up from a small pad of paper he was writing on. “No, what happened?”

“He punched a glass case after the game.”

“Why did he do that?”

“He was frustrated I guess.”

The guard looked at me and titled his head to the side. Squinted his eyes.

“He couldn’t hit something soft?”

Logical question. The big dope.

“Reggie Jackson in No-Man’s Land” is Robert Ward’s celebrated bonus piece on Mr. October. You may have heard of it. Caused a stir when it appeared in the June 1977 issue of Sport. The story is featured in Ward’s entertaining new collection Renegades and is reprinted here for the first time on-line.

Dig in.

By Robert Ward

Reprinted with permission from the author.

Moose Skowron looked like a character out of “Moon Mullins.” Or in a more contemporary sense, he had the appearance of a secondary character in “The Simpsons.” With his lantern jaw, thick jowls, and military crew cut, he possessed the look of a man who could put his fist through your chest and pull your heart out.

Appearances are often deceiving, and they were exactly that with Skowron, who died at 81 on Friday after a battle with lung cancer. Oh, he could be gruff and curt on the outside, but once you opened a conversation with him, you discovered a down-to-earth guy who enjoyed telling stories from his days with the Yankees. And when you’ve played with characters like Mickey Mantle, Hank Bauer, Yogi Berra, and Whitey Ford, or managed for one-of-a-kind legends like Casey Stengel, you’ve got good material to work with.

There were other deceptions with Skowron. Like many fans, I always assumed that Skowron’s nickname came from his size, his power, and his brute physical strength. He was six feet, two inches, 200 pounds, with much of frame wrapped in muscle. Well, the true origins of his nickname had nothing to do with his physical dimensions. When Skowron was a boy, his grandfather gave him an impromptu haircut, which made the youngster look like the Italian dictator, Benito Mussolini. Skowron’s friends called him “Mussolini,” and the family adapted by changing the nickname to “Moose.” By the time he was playing major league ball, everyone was calling him Moose. One of the few exceptions was the Topps Card Company, which always listed him as “Bill Skowron” on his cards.

After signing with the Yankees in 1950, the organization tried him as an outfielder and third baseman, before realizing he lacked the athletic agility needed of those positions. He moved to first base, where he was blocked by players like Johnny Mize and Joe Collins. He finally landed in the Bronx in 1954, when he platooned with Collins, before becoming an everyday player by the late 1950s.

How good was Skowron in his prime? Well, he was very good. From 1957 to 1961, he averaged 20 home runs a season while qualifying for five consecutive American League All-Star teams. During that stretch, he twice slugged better than .500; he also received some support for American League MVP on two occasions.

As a right-handed power hitter, the old Yankee Stadium was hardly made to order for Skowron. But he adapted, developing a power stroke that targeted right-center and right fields, where the dimensions were far more favorable for hitting the long ball. Skowron’s right-handed hitting presence was importance, given that most of their power hitters hit from the left side (including Roger Maris, Berra and the switch-hitting Mantle.) If opposing teams loaded up on left-handed pitching, Skowron could make them pay.

Skowron really had only two flaws in his game. A classic free swinger and bad ball hitter, Skowron could sometimes hit pitches up his eyes, but he could also flail away at other pitches outside of the strike zone. Since he didn’t walk much, his on-base percentage suffered. Skowron’s other weakness involved his health; he simply could not avoid injuries. One time, he hurt his back while lifting an air conditioner. On another occasion, he tore a muscle in his thigh. There were broken bones, too, including a fractured arm that resulted from an on-field collision. With such injuries forcing him to miss chunks of games at a time, he often played 120 to 130 games a season, instead of the 150 to 160 that he would have preferred.

The 1961 season provided contrasts and quandaries for Skowron. On the down side, his slugging percentage and his on-base percentage fell. More favorably, he hit a personal-best 28 home runs while playing in a career-high 150 games. Batting out of the sixth and seventh hole, Skowron provided protection for the middle-of-the-order thumpers, a group that included Maris, Mantle, and Berra.

As he often did, Skowron elevated his play in the World Series. In the 1961 Classic against the Reds, Yet, it was in the 1961 World Series. In five games against the upstart Reds, Skowron slugged .529 with one home run and five RBIs, reached base 45 per cent of the time, and hit a robust .353. Then again, Moose was almost always good in the Series. In 133 at-bats stretched over eight World Series appearances, Skowron hit eight home runs and slugged .519. In Game Seven situations alone, the Moose hit three home runs. If you believe in the existence of clutch, and I do, then Skowron belongs near the top of that list.

Skowron put up another good season in 1962, but his age and the presence of a young player in the system changed his status within the organization. Believing that Joe Pepitone was headed toward superstardom, the Yankees decided to trade Skowron that winter. They sent him to the Dodgers in exchange for Stan Williams, an intimidating veteran reliever who liked to throw pitches up and in as part of his quest for strikeouts.

In some ways, Skowron could not have been traded to a less ideal situation. Newly built Dodger Stadium, which had replaced the Los Angeles Coliseum as the Dodgers’ home, had a ridiculously high mound and outfield measurements that did not favor sluggers like Skowron. He also had to face a new set of pitchers in the National League; outside of World Series competition, Moose had little familiarity with senior circuit pitching. To make matters worse, Skowron did not play first base every day, instead platooning with Ron Fairly. Moose hit a miserable .203 and ripped only three home runs in well under 300 plate appearances.

To the surprise of many, Skowron still had something left for the World Series. Playing against his former Yankee mates, he swatted a home run and batted .385 to help the Dodgers to a four-game Series sweep.

World Series heroics aside, the Dodgers questioned whether Skowron had much left. So they sold him to the Washington Senators. He hit well during a half-season in the Capital City, but when the team fell out of contention, he was sent packing to the White Sox in a mid-season trade. Skowron hit well over the next season and a half, but slumped badly in 1966 before closing out his career in ’67.

Yet, there was much more to Skowron than on-the-field highlights and accomplishments. He made news off the field, sometimes in frivolous ways and sometimes through embarrassing situations. Let’s consider a couple of episodes from the 1960s:

*During the 1963 season, Skowron and several other Dodgers made a guest appearance on the TV show, “Mr. Ed.” Skowron, catcher John Roseboro, center fielder Willie Davis, and Hall of Fame left-hander Sandy Koufax played themselves. In the main plotline of “Leo Durocher meets Mr. Ed,” the talking horse gives batting tips to Durocher, who was billed as the Dodgers’ manager even though he was actually a coach under Walter Alston. Durocher is supposed to relay the tips to a slumping Skowron. Moose and the other Dodgers then watch in amazement as Mr. Ed completes an inside-the-park home run against Koufax. (In a complete aside, Durocher also appeared on an episode of “The Munsters,” and was once again mentioned as the Dodgers’ skipper. Either Alston wanted nothing to do with Hollywood, or someone was trying to send him the message that Durocher was the real Dodgers manager.)

*While training with the Dodgers in Vero Beach, Florida, he decided to make a surprise trip to see his wife at their home in Hilldale, New Jersey. When he arrived at the house, Skowron found his wife in bed with another man. Infuriated by the surprise discovery, Skowron proceeded to pummel his unwanted guest. Shortly thereafter, Skowron was charged with assault, though many were sympathetic to his situation.

Skowron had better long-term success with other relationships, particularly his fellow Yankees. Beloved in the Yankee clubhouse, Moose became especially close friends with Hank Bauer, a rough-and tumble character in his own right. They often made public appearances together, including numerous visits to Cooperstown for Hall of Fame Weekend signings. I remember meeting Skowron and Bauer back in the late 1980s, while I was still working in sports talk radio. They were signing at a table outside one of the many card shops on Main Street. I wanted to interview the two of them, but I was intimidated by Bauer’s raspy voice and Skowron’s rugged appearance. Feeling like a rookie cub reporter, I settled for making a few innocuous remarks to the two ex-Bombers.

It remains one of my regrets. I never did have another chance to interview either Skowron or Bauer. That was a real mistake on my part, losing out on the opportunity to have a real chat with Skowron, one of the game’s great storytellers.

If there is any consolation, some of Skowron’s stories can be found on You Tube, and in the many books that serve as oral histories of the Yankee franchise. This was a guy who was good friends with Mantle and Berra, a guy who knew Whitey Ford, a man who played with Maris, a guy who dealt with the idiosyncrasies of Casey Stengel. Skowron was a man worth listening to, a link to an era that was long ago, but an era that we always want to re-visit.

Moose was a man that we’ll miss.

Bruce Markusen is co-author of the newly revised edition of the book, Yankee World Series memories.

(Photo Credit: Washington Post; Alex Belth.)

[Editor’s Note: Bruce will be on leave for the foreseeable future while he works on a book. We’ll miss his weekly posts and he will drop in occasionally with a Card Corner piece. Meanwhile, we wish him good luck with his project and thank him for being the man.]

Is the shortened season to blame for the injuries to Derek Rose and Iman Shumpert? Mike Wilbon thinks so.

[Photo Credit: Kelly Sullivan]

You can never have enough starting pitching. During the offseason, that was Brian Cashman’s mantra as he built a rotation that went seven men deep. Tonight, it was a lesson the Yankees learned the hard way.

After announcing that Michael Pineda would miss the rest of the season with a torn labrum, the Yankees were looking for Phil Hughes to put his stamp on the rotation. However, those hopes were quickly dashed as the enigmatic right hander couldn’t even pitch his way through the third inning. Even more disconcerting than the four runs he allowed in his brief appearance was the continued lack of command that has dogged him since the second half of 2010. On several occasions, Hughes missed Russell Martin’s target by a wide margin, and almost without fail, the Rangers made him pay.

The Yankees scratched their way back into the game with two runs in the top of the fourth inning, but David Phelps, who may have been auditioning for a role in the rotation, didn’t provide much relief. In 2 1/3 innings, the young right hander allowed three runs, including two long balls, which effectively put the game out of reach. In the process, Phelps’ hiccup probably also quieted any outcry to have him take Hughes spot in the rotation.

With Hughes continuing to struggle and Pineda on the shelf, Andy Pettitte’s outing in Trenton took on even greater importance. In five-plus innings covering 81 pitches, the veteran lefty allowed seven hits and four runs, but was still pleased with his outing. However, he did admit that he wasn’t quite ready to return to the big leagues, which means the Yankees will have to hold their breath with Hughes and Freddy Garcia for at least a few more weeks.

Over the first 18 games, the Yankees have only recorded five quality starts, which, over a similar span, is the second lowest total in franchise history. It probably wasn’t what he had in mind at the time, but, so far at least, Brian Cashman’s pre-season assessment appears to be right on the money. The Yankees most certainly do not have enough starting pitching.

[Featured Image via The Tropical Variation]

Here me blab about the Yanks and sports writing on The Sports Casters podcast. I had a fun time, as always.

[Image via Newmann]