Tomorrow night in the Village, Glenn Stout, Jay Jaffe, Steven Goldman and Dan Barry are the featured speakers at Gelf’s Varsity Letters reading series.

I’m so there.

Tomorrow night in the Village, Glenn Stout, Jay Jaffe, Steven Goldman and Dan Barry are the featured speakers at Gelf’s Varsity Letters reading series.

I’m so there.

If you’ve never read “The Boxer and the Blonde” by Frank Deford, well, here’s a reminder. It’s a good one:

The boxer and the blonde are together, downstairs in the club cellar. At some point, club cellars went out, and they became family rooms instead. This is, however, very definitely a club cellar. Why, the grandchildren of the boxer and the blonde could sleep soundly upstairs, clear through the big Christmas party they gave, when everybody came and stayed late and loud down here. The boxer and the blonde are sitting next to each other, laughing about the old times, about when they fell hopelessly in love almost half a century ago in New Jersey, at the beach. Down the Jersey shore is the way everyone in Pennsylvania says it. This club cellar is in Pittsburgh.

The boxer is going on 67, except in The Ring record book, where he is going on 68. But he has all his marbles; and he has his looks (except for the fighter’s mashed nose); and he has the blonde; and they have the same house, the one with the club cellar, that they bought in the summer of 1941. A great deal of this is about that bright ripe summer, the last one before the forlorn simplicity of a Depression was buried in the thick-braided rubble of blood and Spam. What a fight the boxer had that June! It might have been the best in the history of the ring. Certainly, it was the most dramatic, alltime, any way you look at it. The boxer lost, though. Probably he would have won, except for the blonde—whom he loved so much, and wanted so much to make proud of him. And later, it was the blonde’s old man, the boxer’s father-in-law (if you can believe this), who cost him a rematch for the heavyweight championship of the world. Those were some kind of times.

The boxer and the blonde laugh again, together, remembering how they fell in love. “Actually, you sort of forced me into it,” she says.

“I did you a favor,” he snaps back, smirking at his comeback. After a couple of belts, he has been known to confess that although he fought 21 times against world champions, he has never yet won a decision over the blonde—never yet, as they say in boxing, outpointed her. But you can sure see why he keeps on trying. He still has his looks? Hey, you should see her. The blonde is past 60 now, and she’s still cute as a button. Not merely beautiful, you understand, but schoolgirl cute, just like she was when the boxer first flirted with her down the Jersey shore. There is a picture of them on the wall. Pictures cover the walls of the club cellar. This particular picture was featured in a magazine, the boxer and the blonde running, hand in hand, out of the surf. Never in your life did you see two better-looking kids. She was Miss Ocean City, and Alfred Lunt called him “a Celtic god,” and Hollywood had a part for him that Errol Flynn himself wound up with after the boxer said no thanks and went back to Pittsburgh.

Lost amidst the concerns over the shoulder inflammation experienced by Michael Pineda, one of the most interesting stories of Yankee camp has involved the status of two outfielders who are at a crossroads in their careers. Justin Maxwell and Chris Dickerson are both capable of serving as fifth outfielders on a major league roster, but they are finding no room in a crowded and well-established outfield. The Yankees are set to open the new season with five outfielders, with three of the slots taken by starters Brett Gardner, Curtis Granderson, and Nick Swisher, and the other two going to DH platoon partners Andruw Jones and Raul Ibanez.

Lost amidst the concerns over the shoulder inflammation experienced by Michael Pineda, one of the most interesting stories of Yankee camp has involved the status of two outfielders who are at a crossroads in their careers. Justin Maxwell and Chris Dickerson are both capable of serving as fifth outfielders on a major league roster, but they are finding no room in a crowded and well-established outfield. The Yankees are set to open the new season with five outfielders, with three of the slots taken by starters Brett Gardner, Curtis Granderson, and Nick Swisher, and the other two going to DH platoon partners Andruw Jones and Raul Ibanez.

Unfortunately, the Yankees cannot send either Dickerson or Maxwell to Triple-A, at least not without passing through waivers. Both players are out of options, and both are likely to be claimed by another team if the Yankees try to sneak them through the waiver wire. So the Yankees may be forced to trade one or both of them, or risk losing them for nothing more than the waiver price.

Maxwell, in particular, has opened the eyes of the Yankee brass with his speed, range, and live bat. Like Dickerson, he can play all three outfield positions, which is important given the defensive limitations of Ibanez and the age of Jones. Mad Max might also be the fastest runner in the organization, making him a potential weapon as a pinch-runner. But he’s also 28 years of age, hardly the age of a true prospect, and coming off of major surgery to his throwing shoulder.

So what should the Yankees do? Perhaps the most sensible thing would be to chuck the obsession with a 12-man pitching staff and carry Maxwell as the sixth outfielder. But I just don’t think the Yankees are daring enough to try something different. If that’s indeed the case, then a trade would make the most sense. There are teams, such as the Mets, who are desperately in need of outfield help. With Andres Torres sidelined by leg problems and most of their alternatives better suited to backup or minor league duty, Maxwell could probably start in center field for the Mets right now. The Mets and Yankees hardly ever make trades, but the circumstances might be right for a current exchange, provided the Mets are willing to fork over a C-level prospect from the lower reaches of their minor league system…

***

The injury to Pineda will not only change the configuration of the starting rotation, but it will alter the dynamic of the bullpen. With a healthy Pineda, Freddy Garcia appeared to be the odd man out of the rotation and likely would have been ticketed for long man duty in the pen. Now that Garcia will be starting, the Yankees will have an opening for a long reliever. It figures to be one of three Triple-A prospects: D.J. Mitchell, David Phelps, and Adam Warren. Of the three, Warren throws the hardest, but Mitchell may be best suited to relief work because of his hard sinker.

Earl Weaver would certainly approve of the Yankees’ plan to use a pitching prospect in long relief. The former Orioles skipper was a big believer in breaking in his young pitchers in the relatively pressure-free role of long relief. If they succeeded out of the bullpen, Weaver would then challenge them further by pushing them into the rotation. Weaver certainly had a long record of success with young pitchers in Baltimore, from Jim Palmer and Dave McNally to Doyle Alexander and Ross Grimsley to Mike Flanagan and Scott McGregor.

The Yankees can only hope for similar success from either Mitchell, Phelps, or Warren.

***

After a poor start to the spring training season, Raul Ibanez has shown some life in a body that is closing in on 40. He has hit three home runs over the last week, while showing power to both left and right field. Even if Ibanez had continued to struggle in Grapefruit League play, he was never going to lose his job on the Opening Day roster. Still, the Yankees remain on red alert with regard to the DH position. If Ibanez struggles over the first couple of months of the season, do not be at all surprised if the Yankees cut bait with him and look very seriously at the possibility of signing Johnny Damon. Ibanez is coming off a subpar season in Philadelphia, and given his age, it shouldn’t be any shock if he turns out to be cooked as a major league hitter.

Of all the remaining unsigned free agents, Damon is the best available player. He still has sufficient power and speed to make him dangerous, even if he can’t play the outfield anymore. His OPS of .743 was significantly better than Ibanez’ mark of .707. And he did so without the benefit of having Citizens Bank Park as his home field.

So why hasn’t Damon found a job yet, with the regular season just days away? Damon has been hurt by two factors this off-season: he’s insistent on wanting an everyday DH role because of his pursuit of 3,000 hits, and he’s a Scott Boras client, which can be a discouraging factor to some potential suitors. If Damon were smart, he’d willingly sign as a platoon DH with the Yankees, if only because some playing time is better than no playing time. If Damon were to hit well enough, there’s always a possibility that the Yankees would expand his role and make him the regular DH, though he’d have to concede some DH time to Alex Rodriguez, Derek Jeter, and Nick Swisher. But by continuing to sit on the sidelines, Damon won’t be able to impress anybody.

Yankees aside, I hope that Damon signs with some major league club between now and May. Not only can the man still hit, but he brings an energy to the ballpark and to the clubhouse. He’s a fun player to watch. Without a doubt, Johnny Damon should play somewhere in 2012.

Bruce Markusen writes “Cooperstown Confidential” for The Hardball Times.

Here’s an excerpt from Colum McCann’s “Damn Yankees” essay:

I have been in New York for 18 years. Every time I have gone to Yankee Stadium with my two sons and my daughter, I am somehow brought back to my boyhood. Perhaps it is because baseball is so very different from anything I grew up with.

The subway journey out. The hustlers, the bustlers, the bored cops. The jostle at the turnstiles. Up the ramps. Through the shadows. The huge swell of diamond green. The crackle. The billboards. The slight air of the unreal. The guilt when standing for another nation’s national anthem. The hot dogs. The bad beer. The catcalls. Siddown. Shaddup. Fuhgeddaboudit.

Learning baseball is learning to love what is left behind also. The world drifts away for a few hours. We can rediscover what it means to be lost. The world is full, once again, of surprise. We go back to who we were.

I slipped into America via baseball. The language intrigued me. The squeeze plays, the fungoes, the bean balls, the curveballs, the steals. The showboating. The pageantry. The lyrical cursing that unfolded across the bleachers.

[Photo Credit: N.Y. Daily News]

The Yankees approach the new season with questions surrounding the starting rotation. That’s no surprise, we’ve been talking about those shortcomings ever since Javier Vazquez became the least welcome sequel after Staying Alive (tough choice, lots of terrible sequels).

The surprise is that the Yankees have too many starters now. But once again, they’re having a very hard time finding five of them that are ready to be effective come opening day. Here’s a take on the problem from John Harper in Daily News.

The stats in spring training may be meaningless, but as Phil Hughes demonstrated last year, if you are not ready to answer the bell once the games count, you will get obliterated. So I hope Joe Girardi learned that lesson and will leave behind anyone that can’t cut it.

What if that means leaving Michael Pineda behind? If he’s going to get lit up like Hughes last year, then it’s for the best. But I will have a much happier time this spring if Michael Pineda is pitching well for the Yankees. Revisiting the Montero deal ad nauseum is inevitible, but it won’t be upsetting if Pineda delivers something positive right away.

What’s your rotation now? What’s your rotation once Pettitte is back?

Now: CC, Kuroda, Pineda, Hughes, Nova

Then: Pettitte replaces Nova

If Nova is pitching better than Hughes, that can be amended.

At the beginning of March, Dodgers’ first baseman James Loney talked confidently about being a legitimate candidate for the batting title in 2012. Considering how many people view him as a disappointment, not to mention he has never even hit over .300 in a qualified season, Loney’s optimism was intriguing to say the least. So, last week, I took a look at other batting champions who had never hit .300 before their 28th birthday and, not surprising, discovered very few.

Before writing about Loney’s pursuit of a batting crown, I hadn’t given the first baseman much thought. However, while listening to Vin Scully broadcast a recent Dodgers’ spring training game, the left handed hitter was thrust to the forefront once again. During the game, Scully relayed a story about adjustments Loney had made that the lefty believed would allow him to hit for more power…even as many as 30 home runs this season. Once again, for a player who had never hit more than 15, Loney seemed guilty of wishful thinking.

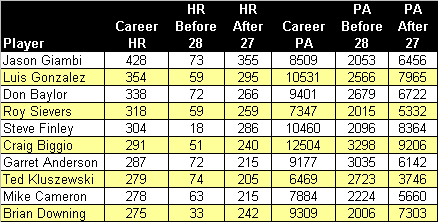

Career Home Run Leaders Among Late Bloomers*

*Includes players with at least 2,000 PAs before their age-28 season who hit 75 or fewer homers.

Source: baseball-reference.com

Since 1901, 685 players (including Loney) with at least 2,000 plate appearances hit 75 or fewer home runs before their age-28 season. From this group, only 31 went on to hit more than 200 home runs in their entire career. Going one step further, only seven batters from this segment hit more than 200 long balls without having recorded more than 15 homers in a season during this timeframe. In other words, if Loney does turn on the power, it will qualify as a historical achievement.

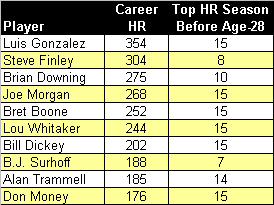

Career Home Run Leaders Among Even Later Bloomers*

*Includes players with at least 2,000 PAs before their age-28 season who hit 75 or fewer homers and never more than 15 in any one season.

Source: baseball-reference.com

To be fair, Loney only implied that he could hit 30 home runs in a season. However, even this accomplishment would go against the tide of history because only 27 players (in 50 seasons) from the group of 685 defined above wound up having their first 30 home run season after turning 28. What’s more, most of those hitters gradually worked their up to 30 home runs, whereas Loney would have to double his output in order to reach that level in 2012.

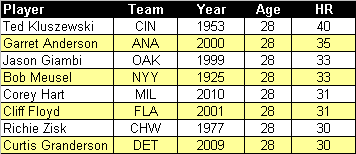

Late Bloomers* Who Had First 30 Home Run Season at Age-28

*Players with at least 2,000 PAs and no more than 75 homers before their age-28 season.

Source: baseball-reference.com

The list above includes three players who offer Loney some immediate hope. For most of his Yankees’ career, Bob Meusel was a productive, but often overlooked member of Murders’ Row. That’s what happens when you play alongside Lou Gehrig and Babe Ruth. By their standards, Meusel wasn’t really a power hitter, but in reality, his more modest totals were still good enough to rank among the league leaders. In 1925, when Gehrig was just breaking in and Babe Ruth was suffering from “the bellyache heard around the round”, Meusel finally was the top dog. That season, the left fielder belted 33 homers to lead the league. It would be the highest total of his career and only his second season with more than 16.

With bulging biceps exposed by his trademark sleeveless uniform, Ted Kluszewski became synonymous with power. And yet, Big Klu was a late convert to the long ball. In 2,723 plate appearances before turning 28, the muscular first baseman only had 74 home runs, or only seven more than Loney. Over the next four years, however, he hit 171, including 40 or more in three consecutive seasons. During that span, no one hit more home runs than Kluszewski, but thanks in large part to several nagging injuries, the slugger’s power quickly dissipated as he combined to hit only 34 home runs in his last five seasons.

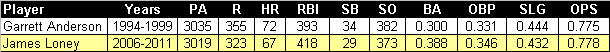

Garrett Anderson vs. James Loney, Pre Age-28 Seasons

Source: baseball-reference.com

Before turning 28, Garrett Anderson’s statistics were very similar to Loney’s. So, if the pattern holds, the Dodgers’ first baseman just might be in line for a breakout power season. In 2000, Anderson, who had only once hit more than 16 homers (21 in 1999), belted 35 long balls, beginning a four-year stretch in which he flirted with that plateau in each season. Considering the similarities, maybe the Dodgers can just go ahead and pencil in more power from first base?

If Los Angeles has a little patience, the real poster boy for late power is Steve Finley. Before entering his age-31 season, the left handed centerfielder had only 47 home runs in nearly 4,000 plate appearances. Then, all of a sudden, he flipped the switch. Not only did Finley belt 30 long balls as a 31-year old in 1996, but he maintained his power over the remainder of his career.

At the rate he is going, James Loney will enter the season convinced he can win the triple crown. Has he made a believer out of you? I am still skeptical, but for the first time, I’ll be keeping a close eye on Loney’s pursuit of history.

Oh, by the way, did I mention this is Loney’s contract year? Ironically, if the Dodgers first baseman does have the breakout season he is predicting, it could mean the end of his days in Los Angeles, especially with teammate Andre Ethier also headed for free agency. Almost 10 years ago, the Dodgers faced a similar situation when Adrian Beltre parlayed a career season into a big free agent contract with another team. The Dodgers were wise to let Beltre go back then, but this time around, a big season from Loney might compel the new ownership group to keep him. In that respect, a lot more than just history is riding on Loney’s 2012 season…millions of dollars are at stake as well.

Kudos to the Grantland’s “Director’s Cut” series for reprinting this gem by the late Paul Hemphill (may he not be soon forgotten).

Here is “How Jacksonville Earned its Credit Card” (from Sport, June 1970):

It must have been the fall of 1962 when I first met Joe Williams. Most newspapermen, at one point or another, succumb to the illusion of public relations — thinking it is the rainbow leading to money and class and peace of mind — and I had just quit writing sports to become the sports publicist at Florida State University. It was football season all of a sudden and I was buried in brochures and 8-by-10 glossies and travel arrangements when Bud Kennedy, the FSU basketball coach, walked in one day and introduced Joe Williams as the new freshman basketball coach. Even then Williams was not the kind to make dazzling impressions. He was quiet and pleasant, tall and hunched over, a man in his late twenties, who grinned out of the side of his mouth and looked up at you, in spite of being 6-foot-4, through bushy black eyebrows. He was, it seems, sort of a part-time coach while doing graduate study or something.7 Florida State was just beginning to flex its muscles in football then, and so Bud Kennedy (who died recently) and assistant coach Hugh Durham (now the head basketball coach at FSU) and, by all means, Joe Williams sort of hovered about like extra men at a picnic softball game.

Joe did have a beautiful young bride named Dale, whom he had met while he was coaching high-school basketball in Jacksonville.8 But she was the only outwardly outstanding thing about Joe Williams, and they lived in what sounded like a fishing-camp cabin in the swamps outside Tallahassee, and I suppose I had his picture taken for the basketball brochure and I suppose the freshman team played out its season. I just don’t know. I went back to newspapering very shortly, and Joe took an assistant coaching job at Furman University, both of us roughly the same age, both of us just looking for a home, and we went separate ways without looking back.9

Jacksonville’s basketball program was, in those days during the early sixties, almost nonexistent. I had seen them play, against teams like Tampa and Valdosta State and Mercer, and it was a twilight zone of dark and airy gyms, small crowds, travel-by-car and intramural offenses. There was a line in the papers about Joe Williams leaving Furman in 1964 to become head basketball coach at Jacksonville University,10 not the most exciting announcement but at least news about an acquaintance. Jacksonville, you could find out if you bought a Jacksonville paper, got progressively worse — from 15-11 to 8-17 in Joe’s first three seasons — and people like me who had known him however vaguely were wondering whatever in the world possessed him to take a job like that.

The Dodgers to go Earvin’s group. Here’s our pal Jon Weisman with the details.

I like this take by Craig Calcaterra over at Hardball Talk. And here is more from Dylan Hernandez in the L.A. Times.

Once Hideki Okajima failed his physical, most Yankee observers assumed that Joe Girardi would carry only one left-hander–the erratic Boone Logan–in the Opening Day bullpen. That situation may have changed now, thanks to the remarkable spring performances of two obscure pitchers, veteran Clay Rapada and minor leaguer Cesar Cabral. The two southpaws have pitched so well in Grapefruit League play that Girardi and Brian Cashman are now considering the possibility of carrying a second left-hander.

On the surface, Rapada is not that impressive. He’s a 31-year-old journeyman who’s pitched for four teams in five years, doesn’t throw hard, and carries a lifetime ERA of 5.13. But thanks to one of the funkiest lefty deliveries I’ve ever seen, he is virtual Kryptonite to left-handed hitters, holding them to a batting average of .153 and an on-base percentage of .252 in his career. Combining funk and finesse, Rapada has clearly demonstrated the ability of overmatching lefty swingers. This spring, he has struck out nine batters in seven innings while not giving up a single run.

Cabral is a lesser known quantity than Rapada, but has the higher ceiling. Very quietly, he was selected by the Yankees out of the Red Sox’ system in December’s Rule 5 draft. He was above average at Double-A Salem last year, pitching to the tune of a 3.52 ERA and striking out 46 batters in 38 innings. With a smooth and fluid delivery, Cabral throws a fastball in the low nineties, topping out at the 95 mile-an-hour mark. He also has an excellent swing-and-miss changeup which can make him effective against right-handed batters. That ability would make him more than a lefty-on-lefty matchup reliever.

Like Rapada, Cabral has been brilliant this spring. The 23-year old has struck out 11 batters and walked only one in eight-plus innings. The Yankees have been duly impressed.

Here’s the trick with Cabral. As a Rule 5 draftee, he has to stay on the Yankee roster all season or be offered back to the Red Sox. If the Yankees try to slip him through waivers, he has almost no chance of clearing; someone will take a chance on a young left-hander with his ability.

If I were a betting man–and I’m not, unless it’s someone else’s money–I’d bet on the Yankees carrying two left-handers on Opening Day. After all, Girardi does love his late-inning matchups. And if I were to wager on either Cabral or Rapada, I’ll predict the Yankees take Cabral. With youth and stuff on his side–not to mention the chance to stick it to Bobby Valentine and the Red Sox–Cabral will be the choice.

By the way, if Cabral makes the Opening Day roster, he’ll become the first Yankee with the name of “Cesar” since Cesar Tovar played for Billy Martin in 1976.

***

In case you’re wondering why you haven’t seen Russell Branyan in any of these Grapefruit League exhibition games, it’s because he remains sidelined with a bad back. The injury has prevented “Russell The Muscle” from playing any games in Florida; somehow the Yankees have been listing him as day-to-day on their pregame notes, dating all the way back to the beginning of spring training.

Branyan’s inability to hit or play the field will likely cost him any chance of making the Opening Day roster. His chances were slim to begin with, but if he could have proven his ability to play a little third base and still hit with some power, he might have been a valuable backup. Now, his best chance of staying with the Yankees could depend on his willingness to go to Triple-A Scranton/Wilkes Barre, where he could be an infield insurance policy. It might be Branyan’s best bet. Given his age and health, I find it hard to believe that any of the other 29 teams would give a guaranteed major league contract to Branyan.

With Branyan pretty much out of the picture, Eric Chavez becomes a lock to make the team as a backup third baseman/first baseman and occasional DH. The question now becomes: who will be the main utility infielder, Eduardo Nunez or veteran Bill Hall?

Clearly the favorite, Nunez is younger, faster, and more athletic. Many observers have already penciled him in as the primary utility infielder, but until the Yankees release Hall, there is a sliver of doubt. While Nunez has more natural talent and youth on his side, Hall has more power and has more experience filling the difficult role of being a part-time player. He also does not have chronic trouble throwing the ball, a habit that plagued Nunez throughout last season. Based on spring training performance, Nunez currently has the advantage. He’s hitting over .300 while Hall is batting in the low .200s.

Perhaps the wise thing to do would be to start the season with Hall, see if he has anything left at the age of 31, and let Nunez compile some regular at-bats in Triple-A. If Hall proves he cannot play, the Yankees can always make the switch to Nunez in mid-season…

***

Very few trades are made during spring training, but the Yankees’ depth in pitching and in the middle infield could result in a deal or two. According to one report, the Yankees have offered Freddy Garcia to the Marlins, but Miami, which has already added free agent Mark Buehrle, wasn’t interested. Still, there are always teams looking for pitching in the spring; the list of Garcia suitors could include the Cardinals and the Tigers. Another rumor has the Yankees talking about a swap of Garcia for Bobby Abreu, but the Angels would have to throw in some money to offset Abreu’s $8 million salary. Garcia is making only $4 million.

On a completely different front, the Phillies, who are currently working without Chase Utley and his ailing knees, have talked to the Yankees about middle infield help. The Phillies are legitimately concerned that Utley will miss the entire season, if not have his career come to an abrupt end. Backup infielder Michael Martinez is also injured, so the Phillies have approached the Yankees about Ramiro Pena, who has no chance of making the Yankees’ Opening Day roster and is destined to start the season for the Scranton/Wilkes Barre traveling baseball show. Pena would likely serve as a defensive caddy behind Placido Polanco, who may be moved back to second base if Utley’s knees are as bad as the Phillies fear.

[Picture by Bags]

Bruce Markusen writes “Cooperstown Confidential” for The Hardball Times.

Chipper Jones said that this year will be his last. Over at SI.com, our man Cliff Corcoran appreciates the future Hall of Famer.

[Photo Credit: Pouya Dianat / AP]