Bernard joins Clyde and Breen tonight to call the Knick game.

Hey Now.

For more on The Kid, check out tributes by Greg Prince and Jason Fry at Faith and Fear in Flushing, Ted Berg over at Ted Quarters, and Jay Jaffe at Baseball Prospectus.

Here’s an ESPN report from the Red Sox training camp:

“When I look at the program we devised, I don’t think of it as tough. But it seems it’s different because a lot of people are frowning. I just asked them to give (it) a few days,” Valentine said, according to The Boston Globe.

“We all know that nobody likes change except for those who are making other people change to do what they want them to do. I happen to be one of those guys who likes change because guys are doing what I want them to do,” Valentine said, according to the report. “I would bet there will be 100 guys who won’t really like it because it’s change for them. But they’ll get used to it.”

…”Everyone says (spring training) is too long. I think that’s baloney,” Valentine said. “To get guys really ready, I think everyone’s working the deadline to get a starter with 30 innings and five (starts). The numbers just don’t compute.”

Ten Hut.

Here’s what I hear on the street on the subway and in my office: talk of Jeremy Lin and the Knicks.

No question the bandwagon is filling up. I’m a bandwagon Knicks fan. First jumped aboard in ’83-’84 when Bernard had that great playoff run. Then a few years later when Pitino coached the team. I rode the highs and lows of the Riley-Van Gundy Era with great passion. I’ve never stopped watching the Knicks but I stopped caring about them or watching them with any kind of devotion.

Now, I’m on the bandwagon again because a New York winter is better when the Knicks matter and the Garden is thumping. And it’s fun to hear people who don’t care about basketball talking about Lin.

All aboard.

The only downside to all the buzz about Jeremy Lin is talk about how Carmelo Anthony is going to spoil all the fun when he returns to the line-up. But over at SI, veteran basketball writer Ian Thomsen doesn’t think that will be the case:

Carmelo Anthony is now the villain. One year ago New York couldn’t wait to trade for him, and now the city fears his return. The fear is Anthony will slow the Knicks’ offense, stop the ball and ruin everything Jeremy Lin has accomplished in the last week.

But look at this from the view of the Knicks’ opponents, who shouldn’t be focused on Anthony as saboteur. Instead, rival teams should be concerned that the breakthrough partnership of Lin and coach Mike D’Antoni — in combination with the bottom-line pressure to win in New York — is exactly what Anthony needs to elevate his career. Instead of fighting the progress of the Knicks, Anthony is likely to embrace it and become better than ever.

That’s what I think is going to happen, because I’ve seen it happen before. It happened to Paul Pierce, who seven years ago was his generation’s version of Anthony. Pierce was a terrific scorer who was viewed throughout the NBA as a sulking, self-indulgent ball-stopper with an array of teamwork skills he didn’t care to use. When Doc Rivers arrived as coach of the Celtics in 2004, he and Pierce had it out. The coach convinced Pierce to push the ball up the floor and share it with less talented teammates in faith that it would circulate back to him.

We shall see. I’m rooting for Melo, though. Better to cheer than to boo, you know?

Jeremy Lin got banged around tonight, had eight turnovers, and then calmly drained a three pointer to win the game.

I yelled so loudly that I scared the wife. Still giddy.

ONIONS!

[Picture by Salehe Black]

Because it came in the wake of the Yankees’ blockbuster trade for Michael Pineda, the acquisition of Hiroki Kuroda has been somewhat overlooked. Even now, the Japanese right hander seems to be getting short shrift on his own team. Recently, Yankees’ pitching coach Larry Rothschild identified Pineda and Ivan Nova as candidates for the number two slot in the rotation. However, if A.J. Burnett is traded and Freddy Garcia is sent to the bullpen, Kuroda will rank behind only CC Sabathia in terms of experience and success as a starter (Kuroda’s 114 games started are almost as many as Pineda, Nova, and Phil Hughes combined). What’s more, over the last two seasons, Kuroda has ranked 36th and 44th in bWAR and fWAR, respectively, which suggests the righty is a solid number two. So, why does it seem as if not too many people look upon him as being one?

Hiroki Kuroda’s Home/Road Splits

Source: Baseball-reference.com

Although the Yankees acquisition of Kuroda has received some appreciation, there has also been hesitation expressed about his migration from the N.L. West to the more talent laden A.L. East. In addition, there have been concerns over the move from pitcher friendly Dodger Stadium to Yankee Stadium and its short right field porch, a fear heightened by the spike in Kuroda’s HR rate last season. However, during his Dodgers’ career, Kuroda hasn’t been a product of Chavez Ravine. Rather, he has pitched just as well on the road as home (3.43 ERA with .661 OPS against vs. 3.48 and .687). Also, an overlay of Kuroda’s batted balls at Dodger Stadium transferred to Yankee Stadium reveals only two additional HRs (doubles in Los Angeles that would have cleared the left field wall, not the short porch, in the Bronx), which hardly suggests a potential long ball epidemic.

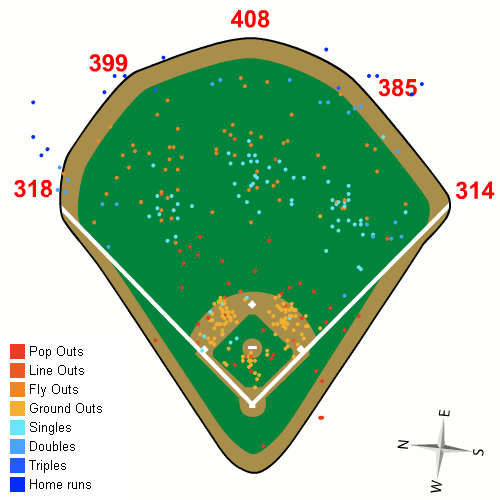

Yankee Stadium Overlay of Kuroda’s Batted Balls at Dodger Stadium

Source: http://katron.org/projects/baseball/hit-location/

There are obvious drawbacks to an overlay, including variables like atmospheric conditions and ballpark-impacted pitch selection (not to mention the accuracy of the simulator). Also, the general trends in Kuroda’s batted ball data suggest an increase in both line drives and fly balls, which doesn’t bode well for his ability to keep opposing hitters in the park. Over his first three seasons, the right hander was able to induce ground balls more than half the time, but in 2011, that rate dropped all the way to 43%. Perhaps more concerning was the precipitous rise in line drives, which seems to justify the spike in Kuroda’s HR rate.

Hiroki Kuroda’s Batted Ball Data

Source: fangraphs.com

Does Kuroda’s move toward being more of a fly ball pitcher represent the start of new trend? It’s hard to tell from one year’s worth of data, but a closer look at the home runs he allowed in 2011 might suggest the increase was more of a fluke. Exactly half of the 24 homers allowed by Kuroda came with two strikes, which was more than double the five he allowed in the two seasons prior.

“I think it’s a random spike, given the information available,” said Joe Sheehan of Sports Illustrated. “The homers themselves were clustered in few outings–the chance that it’s some kind of skill issue is less than it just being a blip.”

In fact, Kuroda’s struggles with two strikes weren’t confined to the long ball. With the exception of 0-2 counts, opposing batters hit well above average against the veteran pitcher in every other two strike combination (click here for a look at how hitters performed with two strikes in 2011). If Kuroda is able to cut down on the damage against him with two strikes, not only might his HR rate return to more normal levels, but his performance could improve across the board. It’s hard to predict whether or not he will be able to make the adjustment, but perhaps pitching against stiffer competition in a more hitter friendly environment will improve his concentration (i.e., pitch selection) with two strikes on the batter? That’s all conjecture, but regardless, Kuroda has substantial room for improvement in two strike counts.

Hiroki Kuroda’s Performance with Two Strikes, 2011

Note: sOPS+ measures Kuroda’s performance against the league average in a particular split. For example, his sOPS+ of 121 in all two strike counts indicates opposing batters hit 21% better against him.

Source: baseball-reference.com

Another concern expressed about Kuroda’s transition to the Yankees is the impact of the team’s porous infield defense. However, according to UZR/150 (which, admittedly, is far from an exact barometer), Yankees’ infielders were at least on par with the Dodgers’ at every position but short stop. Also, based on advanced analyses like Mike Fast’s recent study on catcher framing, Russell Martin ranks as one of the best defensive backstops in the game (according to Fast’s framing data, Kuroda’s catcher in 2011, Rod Barajas, ranked toward the bottom in 2011). Finally, as a group, the Yankees’ outfield led the majors with a UZR/150 of 10.2, which was well above the Dodgers’ rate of 2.8. So, even if Kuroda has gradually become more of a fly ball pitcher, that could play to his advantage on the Yankees, especially if he can get opposing batters to hit the ball to Brett Gardner.

Comparison of Yankees and Dodgers Infield and Outfield Defense, 2011

Source: fangraphs.com

Defense is always an important part of the equation when evaluating pitching, but in Kuroda’s case, it might be a little overrated. Because of his age, and perhaps the perception that he is a control specialist, many people seem to regard Kuroda as a contact pitcher. However, over the last two years, he has proven to be adept at missing bats. Among all qualified pitchers spanning the last two seasons, Kuroda ranks ninth with a swinging strike rate of 10.5%, or two percentage points higher than the league average. If Kuroda can continue to fool hitters, especially during the period when they are learning his patterns, his ability to generate swings and misses could mitigate some of his defense’s shortcomings, if they do exist.

Swinging Strike Rates, 2010-2012

Source: fangraphs.com

There are usually many unanswered questions when a player transitions to a new team and league, so skepticism surrounding Kuroda’s ability to maintain his success in the Bronx is only natural. However, based on his track record and the Yankees’ short-term commitment, there’s every reason to be optimistic that the right hander will be a positive contributor in 2012. Will he be the number two? Such distinctions really have little relevance in the grand scheme of a 162-game season, but if the sentiments expressed by those who know him best are accurate, I wouldn’t bet against it.

The Yankees might actually have a good bench in 2012, something we haven’t been able to say very often over the past decade. With returnees Andruw Jones, Chris Dickerson and Eduardo Nunez and free agent acquisitions Bill Hall and Russell “The Muscle” Branyan all in the mix (and Eric Chavez possibly on the way), the Yankees have a chance to cobble together a decent corps of backup players.

Put me down in favor of the Yankees’ signing of Branyan to a minor league contract. Although he’s 36 and coming off a bad season split between Arizona and Los Angeles (the Angels, not the Dodgers), he has enormous power, the kind of power that makes teams pull out the tape measure when he makes contact. I’ve seen Branyan hit some absolutely monstrous home runs, particularly to center and right-center field. He’s one of the strongest players I’ve ever seen, right up there with Reggie Jackson and Willie Stargell in his ability to hit for sheer length. Of course, he hasn’t hit nearly as many home runs as those two Hall of Famers, so that’s where the comparison has to stop.

Branyan also draws a decent number of walks and has a history of success at Yankee Stadium. (He’s the only player to hit a home run against the glass facing of the center field batter’s eye at the new Stadium, having accomplished that feat in 2009.) The key to Branyan’s situation with the Yankees is this: can he still play third base? If he can, then he gives the Yankees someone who can spell Alex Rodriguez against the occasional right-hander, while also providing backup at first base and at DH.

A check of Branyan’s record at Baseball Reference shows that he appeared in two games at third base for the Angels last season. Prior to that, you’d have to go back to the 2008 season for any prior experience at the hot corner; he made 35 appearances at third for the Brewers that season. So it remains somewhat questionable whether Branyan can log any serious time at third base at this late stage of his career.

If Branyan cannot play third, then his value would lie mostly in his ability to DH against right-handed pitching. As a DH, he would need to revert to his 2010 level in order to be helpful. That summer, he slugged 25 home runs and slugged .487 for the Indians and Mariners.

So there are plenty of questions regarding Branyan. But on a minor league contract, with a relatively small salary coming to him if he makes it to Opening Day, Branyan is worth a look. Besides, how can you not love a guy nicknamed Russell the Muscle?..

***

How do I feel about the possibility of trading A.J. Burnett? Where do I sign? Or perhaps I should say, “Great trade, who’d we get?” Even if the Yankees acquire little of value in exchange for Burnett, they figure to save $3 to $4 million in 2012 salary and can then use that money to add a left-handed DH or another piece to the growing bench. And if Brian Cashman is able to pry a meaningful player out of Pittsburgh in the deal, that’s all the better.

Media reports indicate that three or four teams are interested in Burnett, including the Pirates. The Yankees asked for Garrett Jones in a Burnett deal, but were quickly rebuffed by the Bucs. Jones is a left-handed hitting first baseman/outfielder with power, so he’d be a fit for the role as a platoon DH role and backup outfielder. On the downside, he’s already turned 30, is not a nimble defender, and has seen his OPS fall from .938 to .753 over the past three seasons. Therefore, a player like Jones should not be a dealbreaker. Perhaps the Yankees can throw in another player, or perhaps they can find another match on the Pirates’ roster. How about a left-handed reliever like Tony Watson, who could then compete with Boone Logan and Hideki Okajima for the southpaw bullpen role? Or perhaps a minor league outfielder like Gorkys Hernandez?

The fact that the Yankees are engaging teams in serious discussions for Burnett indicates that the enigmatic right-hander has little future in the Bronx. Even if he’s not traded, he has no guarantee of returning to the rotation. He’ll have to beat out both Freddy Garcia and Phil Hughes for the fifth spot, which is no small task. If Burnett is not traded and has a bad spring, the Yankees still have the option to stick him in the bullpen and use him as a long man. The bottom line is this: Burnett has no birthright to the starting rotation, not after the way he’s pitched the last two seasons.

So start the clock on Burnett’s departure from New York. I’d put it better than 70/30 that he’s an ex-Yankee by the end of the month. Heck, it might happen before the Yankees open camp on Sunday. I’d imagine quite a few readers of Bronx Banter would be pleased by that possibility…

***

Now that Luis Ayala has signed with Baltimore, there may be an opening in the bullpen for another right-handed reliever. It could be filled by Manny Delcarmen, who is one of the more interesting names among the 27 non-roster players that the Yankees have invited to spring training. First, the bad news. Delcarmen didn’t pitch at all in the major leagues last season, and he struggled badly in Triple-A ball for two different organizations. Now the better news. He’s only 29, is durable, has had decent success against the American League East in his career, and has plenty of postseason experience.

In 2007 and 2008, Delcarmen was highly effective as a Red Sox set-up reliever, striking out nearly a batter per inning with a WHIP near 1.00. He has struggled badly since then, resulting in a demotion to the minor leagues last spring. In many ways, he reminds me of Ayala–at one time an effective reliever who has fallen on hard times. He’s just the kind of reclamation project that pitching coach Larry Rothschild specializes in, so it’s worth the relatively small gamble of a minor league contract.

When he’s right, Delcarmen throws in the mid-90s and has an excellent curve ball, which he uses as his out-pitch. Remember, Joba Chamberlain won’t be ready by Opening Day, Burnett could be traded, and Cory Wade, while effective in 2011, seems like a candidate for regression in 2012. So Delcarmen has a chance to make the team as the 12th pitcher–and that might not actually be a bad thing.

[Featured image photo credit: Nick Laham/Getty Images]

Bruce Markusen writes “Cooperstown Confidential” for The Hardball Times.

The Jeremy Lin show hits the road tonight. He’ll face another riveting young point guard, Ricky Rubio, along with Kevin Love and the T Wolves.

Should be fun.

[You can order the Shao Lin t-shirt at shop.akufuncture.com]

I love the “Director’s Cut” reprint series over at Grantland. Today, they’ve got a 1995 New Yorker piece by David Remnick titled “Back in Play.” It’s about Michael Jordan’s return to the NBA:

For my own peace of mind, I talked with two of Jordan’s precursors at the guard position — Bob Cousy and Walt Frazier — and neither had any doubt that Jordan would scrape off the rust in time for the trials of May. Retired ballplayers — especially players of a certain level — are often touchy about the subject of the current crop. They can be grouchy, deliberately uncomprehending, like aging composers whining about the new-fangled twelve-tone stuff. But not where Jordan is concerned. Cousy, who led the Celtics in the fifties and early sixties, and Frazier, who led the Knicks in the late sixties and the seventies, would not begrudge Jordan his eminence.

“Until six or seven years ago, I thought Larry Bird was the best player I had ever seen,” Cousy, who works as a broadcaster for his old team, said. “Now there is no question in anyone’s mind that Jordan is the best. He has no perceptible weaknesses. He is perhaps the most gifted athlete who has ever played this foolish game, and that helps, but there are a lot of great athletes in his league. It’s a matter of will, too. Jordan is always in what I call a ready position, like a jungle animal who is always alert, stalking, searching. It’s like the shortstop getting down and crouching with every pitch. Jordan has that awareness, and that costs you physically. If you do it, you are so exhausted you have trouble getting out of bed in the morning. Not many athletes do it. To me, he hasn’t lost a thing.”

“Leapers are usually not great shooters, but Michael is the exception,” Frazier said. “If you give him a few inches, he buries the jump shot. When he gets inside, his back is to the basket and he’s shakin’ and bakin’ and you’re dead. When he drives, good night. He’s gone. Now that the league has made hand-checking illegal — you can’t push your man around on defense any longer — it’s conceivable that Michael could score even more. I don’t think he’s even sensed that he has more license now. When he does, he’ll be scoring sixty if he feels like it.”

Howard Bryant has a good piece about our increasingly shrill sports culture over at ESPN:

As technology expands and speeds discourse, edges have sharpened. The attraction to and appreciation for high-level competition — ostensibly the reason we watch these golden athletes — disappear as soon as the final gun sounds. The blame game is our new national pastime.

…A couple of weeks ago, Charles Barkley told me he believes this dangerous undercurrent is affecting play.

“Everyone is so worried about whether they win a championship,” he said. “They don’t care about getting there, about having to beat the best to be the best. All they worry about is what is going to be said about them if they don’t get there. I really believe this. Media and expectations have changed everything. Everyone’s afraid of it because if you miss a shot, if you miss a play, that overshadows the whole series, your whole career. So guys just want a ring, but they don’t want to risk losing. If you don’t want to risk losing, you shouldn’t even be playing.”

And this from a piece on Kendrick Perkins reacting to LeBron James’ tweet about a dunk Blake Griffin threw down over Perkins recently (the story is by Mark J. Spears at Yahoo Sports):

“If I was in the same position, in the same rotation, I’m going to jump again and again and again,” Perkins told Yahoo! Sports. “I don’t care. A lot of people are afraid of humiliation or don’t know how to handle embarrassment or would even get embarrassed. I don’t care.

…“You don’t see Kobe [Bryant] tweeting,” Perkins said. “You don’t see Michael Jordan tweeting. If you’re an elite player, plays like that don’t excite you. At the end of the day, the guys who are playing for the right reasons who are trying to win championships are not worrying about one play.”

Last week I heard Jeff Van Gundy refer to a former player as a winner. Not because the player had won a championship but because of the way he practiced and played the game. You can’t be afraid to fail if you are a true professional. Bryant makes a good point. Our sense of appreciation is often overshadowed these days by a willingness to blame and find fault. But that’s like a coke binge, bad vibes feeding off bad vibes. Appreciation is the name of the game. In the NFL, there was little that separated the last four teams. To dwell on the mistakes made by the Ravens, 49ners and Patriots is missing the point.

[Photo Credit: Paul Sancya and Pat Semansky/AP]

Consider me skeptical of Jeremy Lin’s shooting star. A practice squad player turned Garden hero after two impressive performances, Lin makes for a nice story, but I’m not sold on him yet. That said, check out this informative article on Lin by Kevin Clark in the Wall Street Journal:

Conventional wisdom pegs Lin’s recent success as inexplicable. He was undrafted, has been released by two other teams, is rail skinny and before this week, he’d been considered a novelty who many assumed survived with only a Harvard-educated basketball I.Q. But here’s the unusual twist in Lin’s story: His success has little to do with smarts. He is, according to players, virtually unguardable.

Those who have defended him say that Lin has an extremely rare arsenal of moves—the byproduct of posture, bent knees and peculiar fundamentals. And while being a dribbling expert sounds as exciting as being a chef who specializes in porridge, Lin has made it a devastating art. Knicks guard Iman Shumpert, who first guarded Lin during lockout exhibition games and now does in practice, said his possessions play out like this: When he’s close to the basket, he starts an “in-and-out” dribble with his knees bent and his arm straight forward, creating the idea he can go inside or outside—and he does both. All of this is combined with what Jerome Jordan calls a “lethal first step.” Lin is, in short, the NBA’s undetectable star.

“He’s got these moves—he’s so fast and he’s not playing high, he’s playing so low that he’s attacking your knees with this dribble. It’s in a place where as soon as you make a move he just blows past you,” Shumpert said. “To be that low, to have it that far out with your arms, it’s pretty rare. I’ve never seen it.”

Let’s see how he does on the road tonight.

[Photo Credit: Kathy Kmonicek, AP]

Jon Weisman recently set up new digs for Dodger Thoughts. Check it on out. Jon is still the greatest team blogger of ’em all. And if you’ve never read his lasting Yankee Stadium memory, dig it.

Speaking of the Stadium, here’s a good take on the new place by Mathew O’Connor over at Lo-Hud.

Stanley Woodward is best remembered today for a wire he almost sent to Red Smith. Woodward was the sports editor for the New York Herald Tribune and Smith was his star columnist. One spring, according to “Red: A Biography of Red Smith,” By Ira Berkow, “Woodward had been upset with the general sweet fare of columns” Smith had written. “Stanley was about to send a wire saying, ‘Will you stop Godding up those ball players?”

Woodward did not send the wire but Smith never forgot the sentiment. He repeated the story in Jerome Holtzman’s terrific oral history, “No Cheering in the Press Box.”

Woodward ran perhaps the finest sports section in New York after WWII. His Tribune staff included Smith, Al Laney, Jesse Abramson and Joe Palmer.

“Paper Tiger” is Woodward’s classic memoir. Fortunately for us, the good people at the University of Nebraska Press reissued the book not long ago (and it features an introduction from our man Schulian). Woodward’s gem is in print and it is essential reading. (Check out the “Paper Tiger” page at the University of Nebraska Press website.)

Please enjoy this excerpt. Woodward writes about bringing Smith, and Palmer–a writer who is also criminally overlooked these days–to the paper.

From “Paper Tiger,” by Stanley Woodward

Mrs. Helen Rogers Reid blew hot and cold on me at various times during my prewar and wartime career with the New York Herald Tribune. When I came back from the Pacific I felt I was in high favor. Not only had I written reams of copy about the nether side of the war but I worked largely by mail and so had not run up the hideous radio and cable bills the lady was used to receiving for war correspondence.

Mrs. Reid was extremely active in running the paper. She was the actual head of the Advertising Department but in the late stages of Ogden’s life she played a role of increasing importance in the Editorial Department. He started to fail in 1945, and his death occurred on January 3, 1947.

My first day in the office after getting back from the Pacific theater, Mrs. Reid invited me to her office and asked me what I would like to do for the paper. I believe I could have had any job I named at the time. But I asked merely to be returned to the Sports Department which needed reorganization. I asked to go back as sports editor on the theory, held by myself at any rate, that I would be moved out of Sports after the department had been put on its feet.

The first move I made was to install Arthur Glass as head of the copy desk. Our selection of news had been poor during the war and our choice of pictures was abysmal. Glass improved the paper the first day he worked in the slot, which was September 4, 1945.

At this time Al Laney was the columnist and didn’t like the job. He much preferred to handle assignments or to get up a feature series as he had in the case of “The Forgotten Men” before the war.

The first move I made was to attempt to get John Lardner to write our column. The first time we discussed it we renewed the old crap game argument and got nowhere. The second time I took along our publisher, Bill Robinson, and the talk was more businesslike. We met Lardner several other times but couldn’t come to terms with him. The fact was he didn’t want to write a newspaper column and kept making difficulties. So we dropped him, reluctantly.

Even before we talked to Lardner I had been scouting a little guy on the Philadelphia Record whose name was Walter Wellesley Smith. This character was a complete newspaper man. He had been through the mill and had come out with a high polish. In Philadelphia he was being hideously overworked. Not only did he write the column for the Record but he covered the ball games and took most other important assignments.

We scouted him in our usual way. For a month Verna Reamer, Sports Department secretary, bought the Record at the out-of-town newsstand in Times Square. She clipped all of Smith’s writings and pasted them in a blank book. At the end of the month she left the book on my desk and I read a month’s work by Smith at one sitting. I found I could get a better impression of a man’s general ability and style by reading a large amount of his stuff at one time.

There was no doubt in my mind that Smith was a man we must have. After I’d read half his stuff I decided he had more class than any writer in the newspaper business.

At first I didn’t think of him as a substitute for Lardner. Rather I wanted to get them both. When dealings with Lardner came to a stop I was afraid I would have to go back to writing a daily column myself, which I dreaded. I thought of myself at this time as an organizer rather than a writer, but Laney was anxious to have a leave of absence to finish the book he was writing (Paris Herald).

I telephoned Smith and asked him if he could come to New York and talk with me. We set a date and he arrived one morning with his wife Kay. She and Ricie paired off for much of the day while Smith and I discussed business.

It must be said that I was making this move without full approval of the management. George Cornish, our managing editor, knew I was looking for a man but was hard to convince when higher salaries were involved.

It is very strange to me that there was no competition in New York for Smith’s services. He was making ninety dollars a week in Philadelphia with a small extra fee for use of his material in the Camden paper, also operated by J. David Stern. Nobody in New York had approached Smith in several years. In fact, he never had had a decent offer from any New York paper. I opened the conversation with Smith as follows—

“You are the best newspaper writer in the country and I can’t understand why you are stuck in Philadelphia. I can’t pay you what you’re worth, but I’m very anxious to have you come here with us. I think that you will ultimately be our sports columnist but all I can offer you at the start is a job on the staff. Are you interested?”

“I sure am if the money is right,” said Red.

We adjourned for lunch and I told him about the paper and what I hoped to make of the Sports Department. I told him that I had lost all interest in sports during the war but now I was determined to make our department the best in the country.

“I can’t do this without you, Red,” I told him.

I left Smith parked in Bleeck’s and went upstairs to talk to George Cornish. With him it was a question of money and he blanched when I told him how much I wanted to pay Smith. I got a halfhearted go-ahead from George, but still I didn’t dare make the offer to Smith.

He owned a house in the Philadelphia suburbs and would be under great expense until he could sell it and move his family to New York. I suggested that we would perhaps be able to pay him an “equalization fee” until he moved his wife and children into Herald Tribune territory.

I went back to see Cornish and broached this subject. No one can say George wasn’t careful with the company’s money. He argued for a while but finally agreed that if we were to bring Smith to New York, it would be fair to save him from penury during his first weeks with us.

I was able to go back to Bleeck’s and make a pretty good offer to Red. I explained to him that his salary would be cut back after his family moved.

“But don’t worry,” I added. “You’ll be making five times that in three years.”

Of course, it turned out that way. As our columnist, Red was immediately syndicated. His salary was boosted within a couple of months and his income from outside papers equaled his new salary. Before anyone knew it he was making telephone numbers—and he deserved it.

I am unable to account for the fact that none of the evening papers of New York grabbed him. He could have been had, in all probability, for five dollars more a week than we gave him.

With him in hand I was able to let Laney take a few months off to finish his book while I slaved at the column, in addition to other duties. I didn’t want to put Red in too quickly. I wanted him to get the feel of the town first, and also I needed some of his writing in the paper to convince the bigwigs that he was as good as I claimed.

After Smith had been with us a month or so, I talked to Bill Robinson about making him our columnist. I wanted Bill to talk to Mrs. Reid about Smith so that Red would get away from the gate in good order. Bill had been reading him and was enthusiastic about his work. So not long after Smith had shifted his family to Malverne, Long Island, having sold his house, I told him that he was the columnist until further notice.

“I think that means forever, Red. And I’ll go right upstairs and see if I can get you more money.”

As a columnist Smith made an immediate hit and it wasn’t long before the Hearst people were showing interest in him. I told Bill Robinson it was silly not to have a contract with Smith. He agreed and it was drawn up at once. It gave him a large increase in salary and half the returns from his syndicate, which was growing fast. It now includes about one hundred papers.

I’d like to go back to the question of why Smith wasn’t hired by somebody else. My conclusion is that most writing sports editors don’t want a man around who is obviously better than they. I took the opposite view on this question. I wanted no writer on the staff who couldn’t beat me or at least compete with me. This was a question of policy.

I was trying to make a strong Sports Department and it was impossible to do this with the dreadful mediocrity I saw around me on the other New York papers.

The week the Smiths moved from the Main Line to Malverne was memorable. The kids, Kitty and Terry, were dropped off at our farm for a few days so that the parental Smiths could move in peace. I think the kids had a good time playing with our little girls.

Terry, who is now a bright young reporter and a graduate of Notre Dame and the army, was satisfied to sit on the tractor for hours at a time. To be safe I blocked the wheels with logs of wood and took off the distributor cap. The tractor had a self-starter.

With the Smiths established in Malverne, the next move was to get a racing writer. I wrote about twenty-five letters to people in racing—horse owners, promoters, trainers, jockeys, concessionaires, and gamblers. I asked each one whom he considered to be the best racing writer available to the New York Herald Tribune. The response was nearly 100 percent unanimous: “Joe Palmer.”

I asked Smith if he knew Joe Palmer. He said, “Yes, and he’s a hell of a writer.”

I found that Joe had a regular job on the Blood Horse of Lexington, Kentucky, that he was also secretary of the Trainers’ Association and was currently in New York tending to the trainers’ business.

I got hold of Bob Kelley, my old Poughkeepsie associate, and asked him if he would make an appointment for Palmer to meet for lunch in Bleeck’s restaurant at his convenience. Kelley had left the Times and had become public relations counsel for the New York race track. He got hold of Palmer and conveyed my message. Palmer answered as follows, “Tell that son of a bitch I won’t have lunch with him, and if I see him on the street I’ll kick him in the shins.”

I told Kelley that his answer was highly unsatisfactory and sent him back to talk further with Palmer. This time Joe came into Bleeck’s with his guard up. What he didn’t like about me was that I made a specialty of panning horse-racing. But once we got together we were friends in no time.

Joe liked the idea of working for the Herald Tribune. We came to terms quickly. It was agreed that he should go to work for us on the opening day at Hialeah, some months away. He needed the intervening time to finish his annual edition of American Race Horses.

I didn’t know at this time what a remarkable performer I had hired. Palmer turned out to be a writer of the Smith stripe, and his Monday morning column, frequently devoted to subjects other than racing, became one of the Herald Tribune’s most valuable features.

I was misguided in the way I handled Palmer. I should never have tied him down with daily racing coverage. He would have been more valuable to us if I had turned him loose to write a daily column of features and notes as Tom O’Reilly did for us much later. But Joe was effective whatever he wrote. He even did a good job on a fight in Florida one winter, though he hated boxing.

He and Smith were at Saratoga during one August meeting, and Smith persuaded him to go to some amateur bouts, conducted for stable boys and grooms. On their way home Palmer panned the show.

“I’d rather see a chicken fight,” he said.

“Why?” said Smith, outraged. “Chicken fighting is inhuman.”

“Well,” said Joe, “what we just saw was unchicken.”

Palmer was a big man physically and as thoroughly educated as John Kieran. Joe had earned his master’s degree in English in Kentucky and had taught there and at the University of Michigan where he studied for his Ph.D. He could speak Anglo-Saxon. His knowledge of music was stupendous and he would have made a good drama critic for any newspaper.

He had started his thesis at Michigan when he discontinued his education and went to work for the Blood Horse.

He first attracted my attention with a St. Patrick’s Day story in which he revealed that the patron saint’s greatest gift to the Irish was the invention of the wheelbarrow, which taught them to walk on their hind lefts.

Joe, himself, was of Irish decent and was brought up a Catholic. When he moved into a house in Malverne near the Smiths, he didn’t like the public education and sent his children to the parochial school. He decided on this course after a long talk with the mother superior. She asked him if he wanted his children instructed in religion and he said he did.

One day Steve and young Joe were learning the catechism. One of the questions was, “How Many Gods Are There?”

“That’s an important question and I want you to be sure to give the sister the right answer,” said Joe. “Now say this after me: ‘There is but one God and Mohammed is his prophet.’”

The story ends there. Nobody ever found out whether the boys told the sister what Joe told them. It’s a safe bet, though, that their mother, Mary Cole Palmer, touted them off Mohammed.

A few days before Palmer came to work for us, we carried a special story by him explaining his credo of racing and a four-column race-track drawing by the distinguished artist, Lee Townsend. The main point of Joe’s story was, “Horse-racing is an athletic contest between horses.”

He was not interested in betting or the coarser skullduggery that goes on around a race track. For a long time he wouldn’t put the payoff in his racing story.

“Why should I do that?” he asked Smith.

“Because if you don’t, the desk will write it in and probably get it in the wrong place.”

A few days before Joe went to work for us, Tom O’Reilly, another great horse writer, heard about it. He said, or so it was reported to me, “Holy smokes! Those guys will be hiring Thomas A. Edison to turn off the lights.”

Excerpted from PAPER TIGER by Stanley Woodward. Copyright © 1962 by Stanley Woodward. Originally published by Atheneum, a Division of Simon & Schuster, Inc. Excerpted with permission by Scribner, a Division of Simon & Schuster, Inc.

You can order “Paper Tiger” here.

For more on Woodward, check out “Red: A Biography of Red Smith” by Ira Berkow and “Into My Own,” a memoir by Roger Kahn.

And read this about Joe Palmer: blood horse.

(Thanks once again to Dina C. for her expert transcription.)

The Yankees’ rumored interest in free agent utility man Bill Hall is a bit puzzling. Should we interpret that interest as a sign that the Yankees do not believe that Eduardo Nunez can handle the defensive responsibilities of being a utility infielder. Alternatively, is it a signal that the Yankees would like to trade Nunez, perhaps in a deal for a left-handed bat who can fill part of the DH role? To be honest, I’m not sure which of those thought processes are running through the mind of Brian Cashman.

Still, Hall is an interesting player. In 2006, he hit 35 home runs as a starting shortstop and looked like a budding star at the age of 26. Stardom never happened. In 2010, he was a reasonably productive utility man for the Red Sox, filling in around the infield and outfield. Then he signed a free agent contract with the Astros, where he flopped as the team’s everyday second baseman. After being released by the ‘Stros, the Giants took a flier on him, but watched him hit a mere .158 in 38 late-season at-bats.

Now 32 years old, Hall will never be a 30-home run man again, that’s for sure. But if he can revert back to the player of 2010, a versatile player who can play three infield positions and all three outfield positions while hitting with some pop, he’s be a useful guy to have. If not, if his 2011 numbers are an indication of his true current ability, then the Yankees will have to tread lightly here. If they sign Hall and trade Nunez, there may not be a safety net available in the event of a Hall breakdown.

When you’re a baseball fan, it’s funny how the mind works. When I hear the name “Hall,” I think of the Hall of Fame, and I think of past Yankees with the same last name. The Yankees have not had a player named Hall since the now-infamous Mel Hall, who was one of the team’s bright spots during the fallow years of the early 1990s. Hall played hard, pounded right-handed pitching, and delivered his fair share of clutch hits, but then he took some “hazing” of a young Bernie Williams to ridiculous extremes, driving the young outfielder to the verge of tears. He repeatedly referred to Williams as “Zero.” When Williams began talking in Hall’s presence, the veteran outfielder chided him by yelling, “Shut up, Zero.” Why this treatment was allowed to go on unchecked remains one of the great mysteries in Yankee history.

Hall also failed to make friends with the front office when he brought his two pet cougars–yes, a pair of pet cougars–into the Yankee clubhouse without warning, creating a mild panic in the process.

Yet, the hazing and the cougar incident pale in comparison to Hall’s post-career problems. Hall is currently sitting in a federal prison, where he will remain until he is old and gray because of his repulsive relationship with two underage girls. Hall was convicted of sexual assault; he essentially raped the girls, one of whom was 12 at the time of the relationship. Sentenced in 2009, he will have to serve a minimum of 22 years, or the year 2031, before he is eligible for parole. If he does not gain parole, the total sentence will run 45 years, putting him behind bars until 2054. Hall is 51 now, so that would put him at a ripe old 93 years. So who knows if he’ll even live that long.

There is one other “Hall” that I remember playing for the Yankees. He was Jimmie Hall, a left-handed power hitter of the 1960s. He began his career with a flourish, putting up OPS numbers of better than .800 in his three major league seasons with the Twins. As a rookie, he set a record for most home runs by a first-year player in the American League, busting the mark set by Ted Williams in 1939. He also had the ability to play all three outfield spots, making him particularly valuable toMinnesota.

Apparently on the verge of stardom, Hall then fell off the map. He struggled so badly in 1966 that the Twins traded him to the Angels. Some say his early decline was the result of being hit in the head with a pitch. Others pointed to his inability to handle left-handed pitching. And then there were those who felt that he was done in by the changes to the strike zone that hurt so many hitters during the mid-to-late sixties, when the second deadball era set in.

By the time that Jimmie Hall joined the Yankees, he was a fragment of the player who had once torn through the American League. The Yankees acquired him early in the 1969 season, picking him up from the Indians in a straight cash deal. Hall came to the plate 233 times for the Yankees, but hit just three home runs and reached base only 29 per cent of the time. Even in a deadball era, those numbers didn’t suffice.

Hall didn’t last the season in theBronx. On September 11, the Yankees dealt Hall to the Cubs for two players with wonderfully opposite names, minor league pitcher Terry Bongiovanni and outfielder Rick Bladt. If you remember either of those players, give yourself a cigar.

So that’s it for the Yankees’ legacy of Halls. Mel and Jimmie. If the Yankees end up signing Bill Hall, we can only hope that he’ll be a better player than Jimmie and a better man than Mel.

Bruce Markusen writes “Cooperstown Confidential” for The Hardball Times.