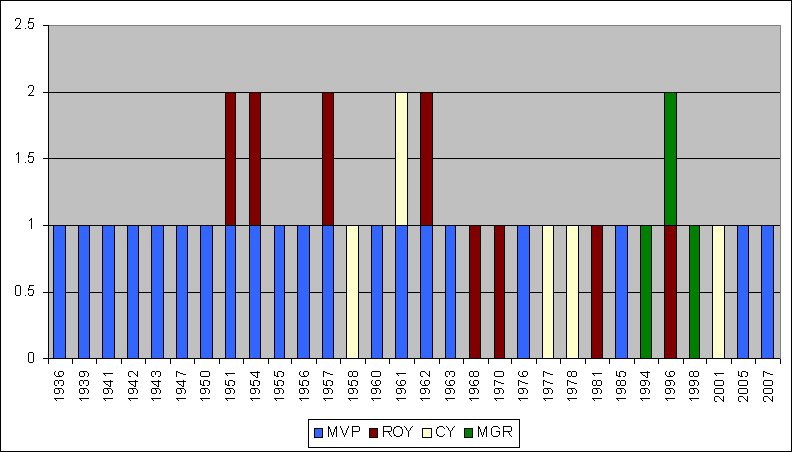

The offseason awards season hasn’t been very kind to the Yankees so far. Ivan Nova and C.C. Sabathia, the team’s respective candidates for the Rookie of the Year and Cy Young, both finished a distant fourth in the voting, but at least that was one slot ahead of manager Joe Girardi, who placed fifth in Manager of the Year balloting. With only MVP left to consider, and Curtis Granderson considered somewhat of a long shot, chances are the Yankees will wind up empty handed.

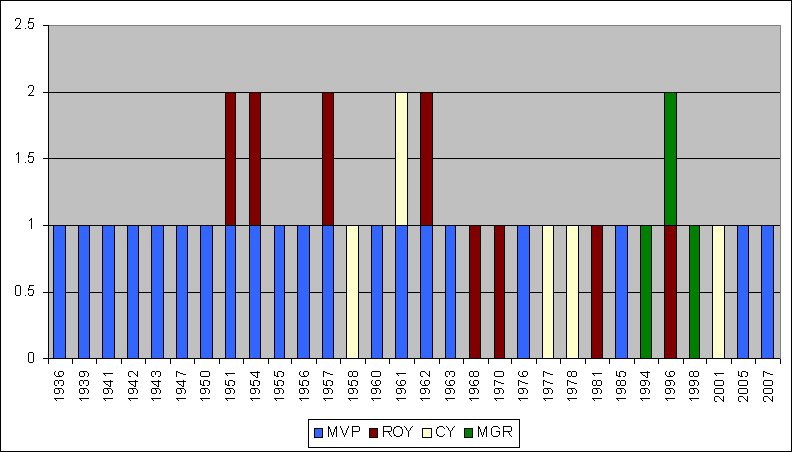

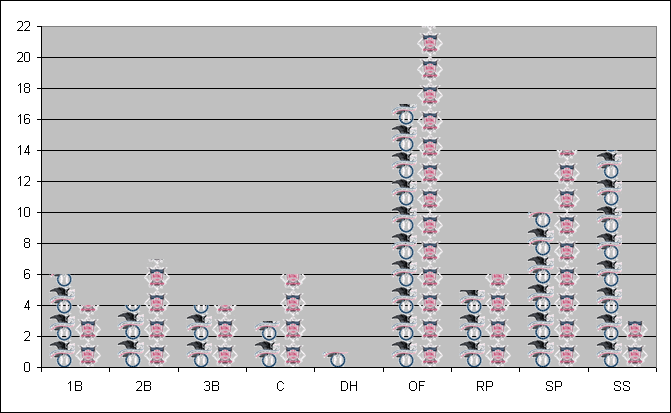

Yankees’ Historical Award Totals

Note: MVP first awarded in 1931; RoY in 1947 (one award until 1949); CY in 1956 (one award until 1967); MoY in 1983

Source: mlb.com

To go along with all of the franchise’s other accolades, the Yankees have had more MVPs than any other team, and also rank among the leaders for all of the other major awards. However, since 1985, only seven awards have been handed out to the pinstripes, and three of those were to the manager. Many Bronx Bomber fans probably view this as evidence of bias against the team within the ranks of the BBWAA, but it might also speak to how well rounded the Yankees have been over the last two decades.

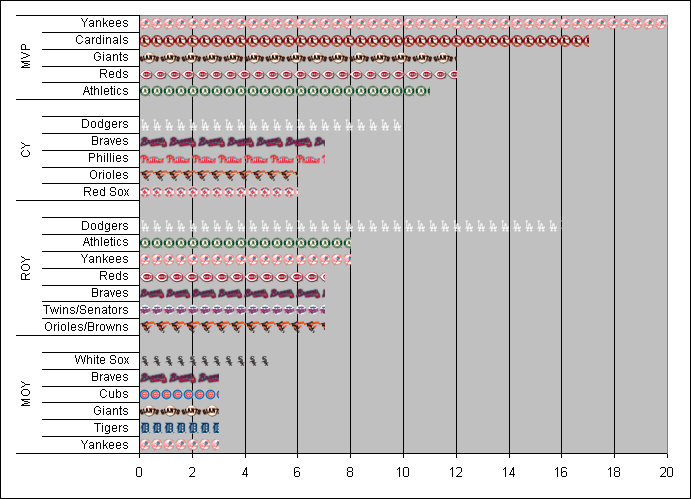

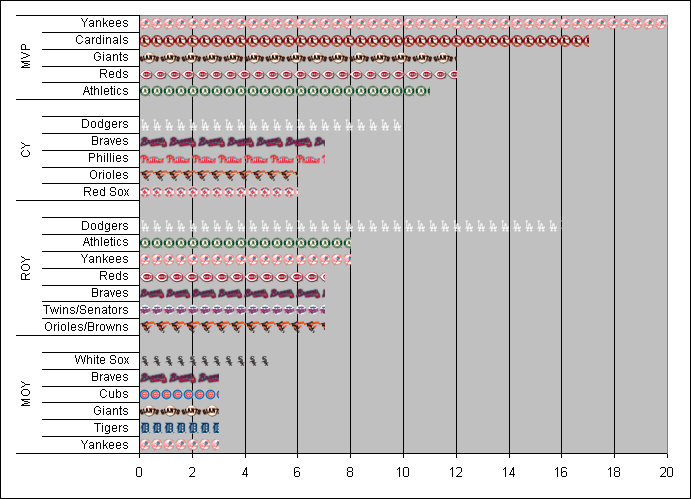

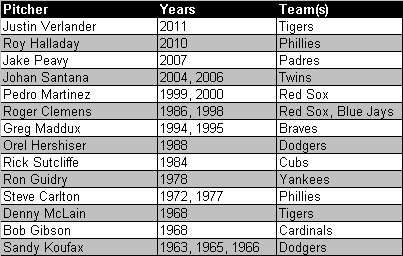

Top Major Award Winners, by Franchise

Source: mlb.com

Since the award was first bestowed upon Jackie Robinson in 1947, the Rookie of the Year has become synonymous with the Dodgers. With four honorees while in Brooklyn and 12 while in Los Angeles, the Dodgers have consistently churned out talented youngsters. The franchise’s 16 Rookie of the Year trophies not only equal the combined total of the next two teams, but also include two stretches of at least four consecutive winners, each of which alone would sum to more awards than the individual totals for 18 other teams. What makes the Dodgers’ RoY dominance even more impressive is the award requires a new winner every season, so having one or two great players doesn’t account for the lion’s share of a team’s total.

Along with the Athletics, the Yankees lead the American League with eight Rookie of the Year winners, but Derek Jeter has been the franchise’s only honoree since Dave Righetti won the award in 1981. Jesus Montero has a good chance to break that drought in 2012, assuming the Yankees are able to find him a position. In the almost 40 years since the DH was created, only the Royals’ Bob Hammelin, who bested Manny Ramirez, has won the Rookie of Year by taking most his at bats as a designated hitter. At this point, that seems to be the Yankees’ plan for Montero, so in order for him to win the honor next season, he’ll have to buck that historical trend.

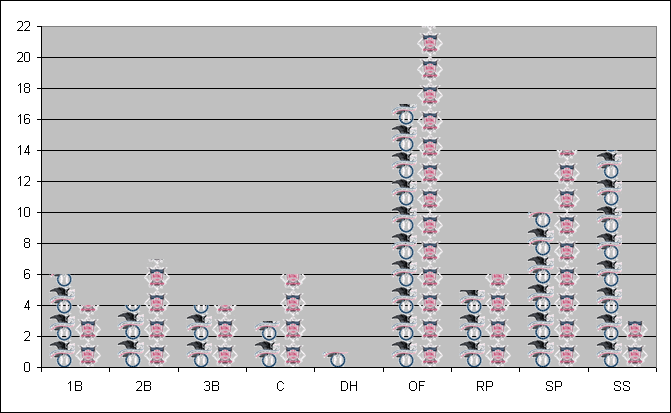

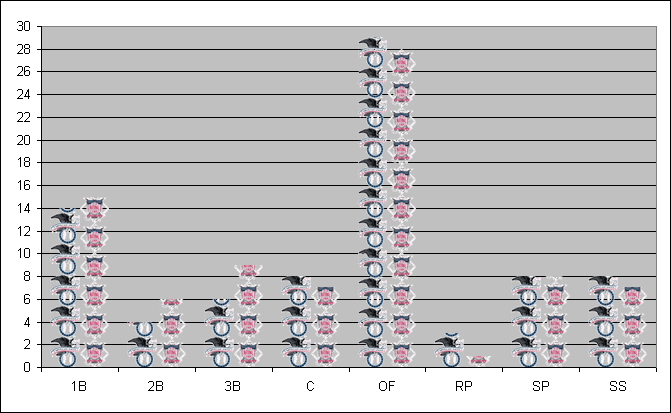

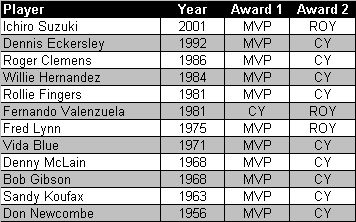

Rookie of the Year Winners, by Position and League

Note: Players considered only at the position they played the most.

Source: mlb.com

Manager of the Year is perhaps the most nebulous of the four major awards. Apparently, a successful manager is not only judged by the performance of his team, but by the lack of payroll allotted to it. That’s unfortunate for Joe Girardi now, but, when he became the only MoY to win the award with a losing record while with the Marlins in 2006, it was Willie Randolph who was left to lament.

Although the MoY is the most recent of the major awards, it rivals the RoY in terms of broad distribution. Only the Mets and Brewers have never had a manager win the honor (the Diamondbacks are the only team without a RoY), meaning more teams have had MoY designees than the Cy Young and MVP (25 teams each), both of which have been around much longer.

This year, both MoY selections made a bit of history. In the A.L., Joe Maddon became the 12th manager to win the award at least twice, while in the N.L., Kirk Gibson joined an even more select fraternity. Along with his 1988 MVP, Gibson’s MoY award makes him only the four person to win both trophies, joining Joe Torre, Frank Robinson and Don Baylor.

Multiple Manager of the Year Winners

Source: mlb.com

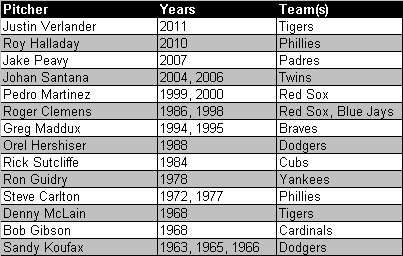

To no one’s surprise, Justin Verlander was unanimously selected as Cy Young in the American League, making him only the 14th different pitcher (and 21st selection) to be so honored. Verlander was also the first Tigers’ starting pitcher to win the award since Denny McLain won it consecutively in 1968 and 1969. Among the pitchers Verlander beat out for the award was C.C. Sabathia, who finished a distant fourth (the big lefty has finished no lower than fourth in the balloting during all three of his seasons in pinstripes). Although Sabathia didn’t seem to get much serious consideration for the top of the ballot, it’s worth noting that fangraph’s version of WAR actually had the Yankees’ ace leading the American League.

In the National League, Clayton Kershaw was named Cy Young, becoming the youngest pitcher to win the award since a 20-year old Dwight Gooden in 1985 and adding to the Dodgers’ major league leading total of 10 honorees. In order to win the award, Kershaw had to beat out reigning Cy Young Roy Halladay, who led the National League in both versions of WAR. Perhaps the electorate has grown a little weary of honoring Halladay, but even so, it’s hard to argue with Kershaw credentials.

Unanimous Cy Young Award Winners

Source: mlb.com

This year’s MVP vote in the American League could be among the closest ever. In addition to prominent candidates from most of the contending teams, Jose Bautista had another phenomenal season, so there is no lack of deserving winners. However, most of the attention has revolved around whether Verlander could, or should, win both the MVP and the Cy Young.

In the 55 years of concurrent history between the two awards, nine pitchers have been named both Cy Young and MVP, and of that total, three of the last four have been relief pitches. So, needless to say, the BBWAA has been at least a little reluctant to give the MVP to a player who takes the field less than 40 times per season. But, was Verlander’s 2011 campaign strong enough to mitigate that reticence?

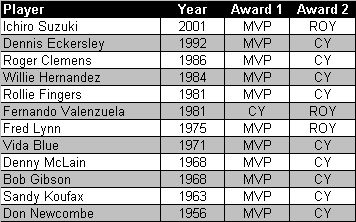

Players Who Have Won Two Major Awards in One Season

Source: mlb.com

Regardless of where you come down on the Pitcher-as-MVP debate, Verlander stands on the verge of an even more select accomplishment. Should the Tigers’ right hander add to his trophy case next week, he’ll join Don Newcombe as the only player to be honored as a RoY, Cy Young, and MVP. The Newk, who was voted the top rookie in both leagues for 1949, was named MVP and Cy Young five seasons later in 1956 (he missed three years to his service in the Korean War). If Verlander is similarly honored, he will have taken the same path to join Newcombe.

In the National League, the MVP race seems to be a two horse race, with Ryan Braun having the edge over Matt Kemp because of the relative success of his team. If the two players do finish 1-2, it would be appropriate for several reasons, not the least of which is both men recently signed mega-contract extensions that will pay them over $20 million per season into the next decade. Needless to say, the Brewers and Dodgers will be hoping this isn’t the last time Braun and Kemp find themselves atop the MVP balloting.

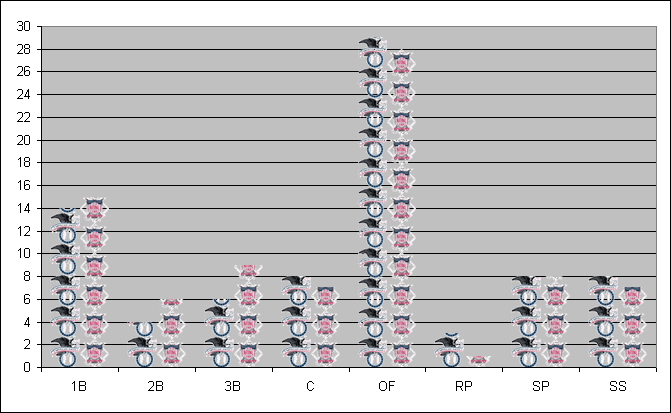

MVP Winners, by Position and League

Note: Players considered only at the position they played the most.

Source: mlb.com

The baseball awards season not only provides a cap on the current year, but also the perfect segue into the Hot Stove. Before too long, fans will be digesting their team’s winter acquisitions and projecting which players are poised for a break-out season. Among that group could be next year’s major award winners, but those future Cy Youngs, RoYs and MVPs will have to wait. The spotlight still belongs to this year’s Boys of November.