My Dad died on this day 7 years ago. I just learned that today is also National Hot Pastrami Day.

Fitting.

My father was a Sid Caesar man. Your Show of Shows and Caesar’s Hour trumped Benny, Berle, and Gleason.

So when My Favorite Year came out, Dad was eager to take his children to see it. I was eleven years old and we went one Saturday afternoon to the Paramount. I always loved that theater because it was underground. Dad fell asleep during the movie but my brother, sister and I enjoyed ourselves. It didn’t matter that Dad passed out (he was still boozin’ then). The subject meant something to him. The movie was funny and sentimental. And O’Toole was nominated for an Oscar.

And Dad woke up for the finale:

[Photo Via: Cinema Treasures]

Head on over to SB Nation and check out a memoir story I wrote about my father and the two Rogers–Angell and Kahn. Leave a comment over there if you dig it.

Thanks.

My Dad’s family wrote letters, lots of them. And saved them, too. My father taught my sister, brother, and me how to write letters and to value them, not just as a way of saying “thank you” for a gift but as a way of communicating. I think he preferred writing letters to talking–and he loved to talk–because in a letter he could be more exact and clear than he could in person or over the phone. He often was so infatuated with his words that his style, the way he phrased things, became more important than what he said. And he typed his letters always.

I’ll never forget the delicate “Par Avion” envelopes that came from my mom’s family in Belgium, either. They were handwritten and in French but still, they were small treasures, slightly mysterious, always full of promise. Getting a letter made me feel special. After all, someone had taken the time to sit down, write out their thoughts, put the paper in an envelope, place a stamp on it, then drop it in a mailbox.

I write letters occasionally now, a few people I know don’t use e-mail and that’s the best way to get them. Some e-mails I write as letters, and it’s only recently that I’ve broken the habit of starting each e-mail, “Dear so-and-so.” I was told that wasn’t appropriate for business e-mails, go figure.

I got to thinking about letters the other day after reading this Talk of the Town piece by Roger Angell in The New Yorker:

Letters aren’t exactly going away. Condolence letters can’t be sent out from our laptops, and maybe not love letters, either, because e-mail is so leaky. Secrets—an expected baby, a lowdown joke, a killer piece of gossip—require a stamp and a sealed flap, and perhaps apologies do as well (“I don’t know what came over me”). Not much else. E-mail is cheap, and the message is done and delivered almost as quickly as the thought of it. The sense that something’s been lost can produce the glimmering notion that overnight mail itself must have been a sign of thrilling modernity once. The penny post (with its stamps and its uniform rates) arrived in the United Kingdom in 1840, and in the decade that followed Anthony Trollope, a postal inspector, was travelling all over Ireland on the swift new express trains and persistent locals, to make sure that every letter, wherever bound, was actually being delivered the next day. On those same trains, he sat and wrote novels, and in the novels dukes and barristers and young M.P.s and wary heiresses and country doctors were writing letters that moved the plot along or reversed it or tilted it in some way. The restless energy of Victorian times, there and here at home, demanded fresh news and lots of it. I myself can recall the four-o’clock-in-the-afternoon arrival of the second mail of the day at our house when I was a boy, and the resultant changes of evening plans.

If we stop writing letters, who will keep our history or dare venture upon a biography? George Washington, Oscar Wilde, T. E. Lawrence, Virginia Woolf, E. B. White, Oliver Wendell Holmes, Vera Nabokov, J. P. Morgan—if any of these vivid predecessors still belong to us in some fragmented private way, it’s because of their letters or diaries (which are letters to ourselves) or thanks to some strong biography built on a ledge of letters. Twenty years ago, many of us got a whole new sense of the Civil War while watching and listening to Ken Burns’s nine-part television documentary, which took its poignant tone from the recital of Union and Confederate soldiers’ letters home. G.I.s in the Second World War wrote home on fold-over V-Mail sheets. Troops in Afghanistan and, until lately, Iraq keep up by Skype and Facebook, and in some sense are not away at all.

[Photo Credits: The Terrier and Lobster]

It’s hard to figure that it’s almost been five years since my Dad passed away. I got to thinking about him on the subway this morning when a man came on the train with a bible in his left hand and started talking about Jesus. The man through the packed car slowly and was ignored by the passengers. I smiled as I remembered something Dad once said to a subway preacher. Dad looked up from his book when the preacher got close, looked up at him and in a loud, clear voice said, “Sir, your arrogance is breathtaking.”

Ah, the old man was a good one.

In the fall of 1984, my brother, sister and I met Mike Fox, one of my dad’s old friends. My sister and I were thirteen. A few months later, Mike and I started a correspondence that continues to this day. Here’s his first letter to me.

ll

There is a moving Father’s Day piece by Charles M. Blow over at the New York Times that is worth your time:

It was the late-1970s. My parents were separated. My mother was now raising a gaggle of boys on her own. She was a newly minted schoolteacher. He was a juke-joint musician-turned-construction worker.

He spouted off about what he planned to do for us, buy for us. But the slightest thing we did or said drew the response, “you jus’ blew it.” In fact, he had no intention of doing anything. The one man who was supposed to be genetically programmed to love us, in fact, lacked the understanding of what it truly meant to love a child — or to hurt one.

To him, this was a harmless game that kept us excited and begging. In fact, it was a cruel, corrosive deception that subtly and unfairly shifted the onus of his lack of emotional and financial investment from him to us.

I lost faith in his words and in him. I stopped believing. Stopped begging. Stopped expecting. I wanted to stop caring, but I couldn’t.

Meanwhile, over at Grantland, Jane Leavy has a piece on her old man:

When my father realized he was going blind he took up golf.

Empirical evidence of his loss of vision was plentiful — the run-in with a pickup truck that nearly decapitated my dozing mother in the passenger seat of the car; the Patrick O’Brian novels he could no longer read; the eye drops that never did any good; the dreaded ophthalmological pyramid of letters projected in a dark room in a dark world growing more occluded every day.

But, he did not accept the brutal, unwavering diagnosis — Macular Degeneration — until the guys in his regular tennis game, the guys he’d been playing with every Sunday for 30 years, told him not to show up again. The realpolitik of sport, every sport, at every level of competition, is cruel and uncompromising. Even he could read the writing on that wall.

[Photo Credit: L.A. Times]

My father was an incorrigible name dropper. He called famous actors and directors by their first names, suggesting an intimacy that didn’t always exist. He had met a lot of celebrities when he worked as a unit production manager on The Tonight Show. One chance encounter with Richard Pryor and he was “Richie” forever. Dad reached the heights of chutzpah when he went to the theater with a friend one night and spotted the actress Gwen Verdon. He walked down to her, introduced himself, and kissed her on the cheek as if they’d known each other for years. Ms. Verdon was delighted. Dad’s friend was amazed.

I remember watching “12 Angry Men” with the old man when I was a kid. “It’s almost as good as the original,” he said, referring to the TV production. “You see how exciting a movie can be even if it takes place in one room?”

I was captivated and by the end, I felt intelligent, finally on the right side of the line that separates boys and men. It was directed by “Sidney,” Sidney Lumet. They had crossed paths once; Dad had wanted to turn “Fail Safe” into a movie, a project that Lumet eventually directed. The old man admired Lumet not just because he was a fellow New Yorker but also because they shared a similar aesthetic, a love of the theater and actors. Dad was an avid theatergoer starting in his early teens through his mid thirties when he became an independent documentary producer. He revered Lumet’s quick and efficient approach to shooting a movie.

“Sidney always comes in under budget and has it in his contract that he keeps the difference,” he told me, raising his eyebrows. “Now, that is a smart man.”

Not long after my mother kicked him out, Dad saw “The Verdict” and raved about the performance Lumet got out of Paul Newman as a lawyer who became an alcoholic when he got screwed over, then sobered up when the chance for redemption arose. His clients got justice, he got back his self-respect, and I got squat because I was 11 and Dad said that was too young to watch the movie. The closest I got was the commercials on TV. Everything looked dark brown, courtrooms and bars alike, and Newman seemed so frail I didn’t even notice his famous blue eyes.

Dad holed up on his own in Weehawken, across the Hudson, after his next girlfriend gave him the boot as well. There were two things that he liked about New Jersey: the view of New York City from his bedroom window, and that the liquor store down the block opened before noon on Sundays.

I remember visiting him without my brother or sister one time in January 1983, shortly after “The Verdict” came out. It was a late Saturday afternoon, almost dark, and the sun reflected off the tall buildings overlooking 12th Avenue. The old man was lying on his bed in his underwear and t-shirt smoking a Pall Mall. The heating pipes clanged. The windows were sealed shut around the edges by duct tape but still rattled when it got windy. A glass of vodka sat next to the ashtray on his night table. I used to fantasize about emptying his Smirnoff bottle in the kitchen sink and filling it back up with water. But I never had the nerve.

Most of the time he’d make me entertain myself on the other side of the apartment, in the room without a view of the city. He didn’t want me reading comic books but I did anyway. Or I’d trace the movie ads from the Sunday paper. “The Verdict” was nominated for five Oscars including best actor and best picture. The movie ad showed Newman in a rumpled white shirt, tie loosened, his eyes half closed looking down. The light from a window washed over his face. He looked defeated. The text above read: “Frank Galvin Has One Last Chance at a Big Case.” I traced the movie poster and then drew it freehand. I felt the seriousness of the title “The Verdict.” I didn’t know what that term meant and didn’t ask.

Now I was content to sit next to Dad on his bed and look out the window at the orange light bouncing off the New York skyline. The view reminded us of how far we were from where we wanted to be.

There was a small black-and-white TV on the chest at the foot of the bed. An episode of M*A*S*H, the old man’s favorite show, ended. The familiar and mournful theme song, “Suicide is Painless” filled the room. Dad was talking about his girlfriend. He didn’t seem too bothered by their breakup. Leaving Manhattan was the bigger issue. With Mom, he was devastated. He still believed she was foolish to divorce him and was convinced that one day she’d come to her senses and have him back

Soon enough Dad returned to the subject of Sidney because Lumet directed the Saturday Afternoon Movie. “He always comes in under budget, do you know why? Because Sidney is not stupid, that’s why.”

“Dog Day Afternoon” was on TV: an Al Pacino movie for grown-ups, but Dad let me watch it with him anyway. Maybe the vodka he was drinking softened his resolve. I knew enough not to question why. Pacino—Dad called him “Al”—played Sonny, a little guy who robbed a bank in Brooklyn. The movie was about what happened in the inside of the bank with Sonny and the hostages. It was tense but parts were funny and I laughed when Dad laughed.

During a commercial break, I saw that his eyes were closed. I studied him. His stomach inflated and deflated in short, hard spurts. Dad was forty-five, almost six years removed from a heart attack, and his deep, uneven breathing worried me. He flexed his right foot and his big toe cracked so I knew he wasn’t asleep. Maybe he was meditating. He opened his eyes and smiled at me, put his hand over mine and looked back at the TV. When he took it away, it was to reach for another cigarette. I stared at the movie until I heard him start to snore. So I slipped out of bed, moving like a cat on the branch of a tree, and butted out his cigarette in the ashtray sitting on a table covered with burn marks. Then I climbed back into bed, careful not to rouse him. I wasn’t sure what was going to happen to the old man. He didn’t have a job and wasn’t in show business anymore. If only he would quit drinking.

I checked to see the progress of the light on the skyscrapers during the commercials. The orange glow began to fade as the sun set, turning softer, then pink as the sky darkened to a purplish blue. I thought of what Dad said when Channel Five ran the same public service announcement every night: “It’s 10:00 p.m. Do you know where your children are?” He’d say, “No, I don’t know where they are. I know they are not with me and that makes me very sad.” He told me so himself.

In “Dog Day Afternoon,” things were only getting worse for Al. It was nighttime in Brooklyn in the middle of summer and the air conditioning in the bank was turned off. The cops brought his boyfriend, Leon, to speak with him on the phone. Al was robbing the bank so he could afford a sex-change operation for the guy. That made sense to me. It was the right thing to do.

At last, the cops agreed to give him an airplane to escape. I imagined what the inside of the plane looked like and where they were going to go. But when they got to the airport, the FBI nailed him, the hostages were freed, and the movie was over.

I put my hands behind my head, lay back and looked at a water stain on the ceiling. I thought about Al, pushed onto the hood of the car at the airport, the loud sounds of planes taking off and landing in the background. His eyes looked like they were going to bug out of his head and he was on his way to jail which didn’t seem fair even though he was a criminal. Then I imagined Paul Newman. I was happy the old man had let me be a grown-up with him for a little while.

The white lights of Manhattan were twinkling on the other side of the Hudson when he woke up and refreshed his drink. I didn’t want to say anything stupid so I kept my mouth shut. Another cigarette smoldered in the ashtray. He picked up the New York Times crossword puzzle and said, “Good old Sidney. He never left New York.”

My father was a schvitzer. Schvitz is a Yiddish word for sweat. His mother was a schvitzer too (but only on one side of her face, it was the strangest thing). I remember calling the old man during the summer months. “How you doin’, Pop?”

“Wet,” he’ say, or “Damp,” or “Moist.” Sometimes he’d just say, in his best Zero Mostel: “HOT.”

I thought of the great family schvitzer last night watching Alfredo Aceves on TV. I have never seen a baseball player sweat like that. The bill of his cap was water-logged after a few batters, thick drops of perspiration falling in his face. Aceves was in trouble in the sixth inning, but then Brett Gardner froze at third on a passed ball, Derek Jeter to hit into a double play. Aceves didn’t stop sweating but he saved the rest of the bullpen and finished the game.

Hey Aceves, this schvitz’s for you.

[Photo Credit: Weegee]

I love to talk but when it comes to writing I have learned that you can talk too much. You can talk a story out before you’ve finished–or started–writing. Some talking is good because it helps formulate your thinking but I’ve discovered that it can go too far.

Talking comes naturally. When I was younger I talked because I was anxious, talked because silence was terrifying. But talking also runs in the family. My twin sister loves to talk. My old man was a champion talker. He loved the sound of his own voice. He talked instead of working. (Maybe that is why I am attracted to but mostly repulsed by Fran Lebovitz.) On the other hand, my mother walked the walk; she was pragmatic, a worker, not a dreamer.

I got to thinking about talking when I read this piece on James Agee by John Updike, a review of “Letters of James Agee to Father Flye”:

Alcohol—which appears in the first Harvard letters (“On the whole, an occasional alcoholic bender satisfies me fairly well”) and figures in almost every letter thereafter—was Agee’s faithful ally in his “enormously strong drive, on a universally broad front, toward self-destruction.” But I think his real vice, as a writer, was talk. “I seem, and regret it and hate myself for it, to be able to say many more things I want to in talking than in writing.” He describes his life at Harvard as “an average of 3.5 hours sleep per night; 2 or 3 meals per day. Rest of the time: work, or time spent with friends. About 3 nights a week I’ve talked all night. . . .” And near the end of his life, in Hollywood: “I’ve spent probably 30 or 50 evenings talking alone most of the night with Chaplin, and he has talked very openly and intimately.” And what are these letters but a flow of talk that nothing but total fatigue could staunch? “The trouble is, of course, that I’d like to write you a pretty indefinitely long letter, and talk about everything under the sun we would talk about, if we could see each other. And we’d probably talk five or six hundred pages…”

He simply preferred conversation to composition. The private game of translating life into language, or fitting words to things, did not sufficiently fascinate him. His eloquence naturally dispersed itself in spurts of interest and jets of opinion. In these letters, the extended, “serious” projects he wishes he could get to—narrative poems in an “amphibious style,” “impressionistic” histories of the United States, an intricately parodic life of Jesus, a symphony of interchangeable slang, a novel on the atom bomb—have about them the grandiose, gassy quality of talk. They are the kind of books, rife with Great Ideas, that a Time reviewer would judge “important.” The poignant fact about Agee is that he was not badly suited to working for Henry Luce.

When I first saw Eric Puchner’s GQ story, “Schemes of My Father” last week, I ignored it. Too close to home, I figured. From the sounds of the title it could have been my old man he was writing about. So I stayed away, but eventually, I went back, read the lead and was hooked. Turns out Puchner’s father wasn’t much like mine at all–a schemer of a different color–but I’ll tell you this: I aspire to write as well as Puchner. Here is is describing his father’s pretensions, having moved his family from Baltimore to California:

Growing up, I’d more or less sub scribed to his Gatsbyesque invention of himself as an aristocrat. There were the ascots, of course, usually paired with tweed. He liked to go bird hunting on the weekends, despite being a terrible shot. For a brief period he insisted we dress up for dinner every night, which for my brother and me meant coats and ties. He boarded horses in the country and prodded my oldest sister to take up polo. He refused to let us wear baseball caps indoors and liked to keep a Manwich-thick wad of cash in his billfold, flaunting it in front of cashiers. Even before the ascots and the polo, he’d saddled his children with increasingly absurd names meant to conjure riding breeches and hunt clubs: Alexander, Laurel, Pendleton, and his pièce de résistance, my own: Roderic. I didn’t know that my dad had been one of the poorest kids at his wealthy private school in Milwaukee, and so I’d always accepted these affectations as part of my father’s identity, as essential to who he was as his love of bratwurst.

Now, though, his blue-blooded habits began to seem absurd. For the first time I saw them in the same light as my own desperate attempts to fit in, which had begun to seem absurd to me as well. Despite an aggressive marketing campaign, I’d failed to become Californian in a way that would convince anyone but the drunkest tourist. I wore jungle-print Vans and shirts with wooden buttons and Wayfarers that were also made, inexplicably, of wood. I had a white Op poncho that I liked to wear with nothing underneath, thinking I looked like Jim Morrison on the cover of Morrison Hotel. My moment of reckoning came when I was at the mall with my best friend, Will, another East Coast transplant, and some surfers called me a “dingleberry.” I had to ask Will what a dingleberry was, and his graphic description made such an impression on me that I went home and took off all my clothes and hid my jungle-print Vans at the back of the closet.

Soon after that, I bought my first punk record—Los Angeles, by X—and began to discover another California, one far removed from the beach bunnies and slack-eyed surfers who’d seemed to me like the epitome of West Coast cool. Minutemen, Black Flag, the Dream Syndicate: The songs coming out of my turntable were about as unsunny as could be, noisy and weird and full of anger at the well-tanned rich. And the singers, Californians themselves, weren’t afraid to be smart. I started dressing like my old self again, slipping off to Hollywood clubs whenever I could, amazed at all the pale, black-booted kids pogoing in flannel. It was a culture as distant from my dad’s beach-club ambitions as you can possibly imagine.

* * * *

It’s this real California—and not the one my father invented for us—that I still call home, one that’s closer to my heart than any place on earth. There’s something about my father’s love for the state, no matter how misdirected it was, that seems to have seeped into my blood. Or perhaps it’s the love itself that I love. Which is to say: Even if the dream isn’t real, the dreamers are. There’s something about the struggling actors and screenwriters and immigrants who live here, the pioneer spirit that despite everything still brings people to the edge of America in search of success, that makes me feel at home.

“Schemes of My Father” is one of the most absorbing and well-crafted stories I have read in a long time. I feel richer for having read it.

For more on Puchner, who is a novelist and short story writer, check out his website.

My old man used to drink at The Ginger Man, a restaurant near Lincoln Center. The place was named after the play based on J.P. Donleavy’s novel. Patrick O’Neal, one of the owners, had stared in the short-lived play. The novel, was reissued not long ago, and over at The Daily Beast, Allen Barra calls it “the funniest novel in the English language since Evelyn Waugh.”

Okay, so this one’s from Katz’s Deli downtown not the Carnegie. They make a better pastrami anyhow, still one of the very few places that slices the pastrami by hand which allows for all the fatty goodness.

Speaking of which, my brother used to go to the 2nd Avenue Deli with my old man all the time. One time, they sat down and dad started in on the complimentary cole slaw. He was a fast talker and a fast eater. He started to choke on the salad just as the waiter arrived. My brother ordered two pastrami sandwiches while the Old Man, eyes wet, face red, downed a glass of water. Before he finished drinking he held up his hand to the waiter. Put the glass down, out-of-breath, and said, “Fatty.”

[Photo Credit: Rachelleb.com]

Roger Angell was the first baseball writer I can remember. Actually, it was the two Rogers–Angell and Kahn–whose books were in my father’s collection, and sometimes–I’m sure I’m not alone here–I confused them. But when it came time to actually reading them and not just noticing the jacket cover of their books, Angell was my guy. Years later, when I started this blog, Angell served as a role model. Not because I wanted to copy his style or his sensibility, but because he was an example of fan who wrote well and loved the game.

So long as I was authentic and wrote with dedication and sincerity, I knew I’d be okay. Angell came to mind recently when I read a blog post by the veteran sports writer, David Kindred:

Bill Simmons is America’s hottest sportswriter. Fortunately, at the same time I came up with an explanation that enabled me to continue calling myself a sportswriter. Bill Simmons has succeeded because he is not, has never been, and will never be a sportswriter. He’s a fan.

Lord knows, there’s nothing wrong with being a fan. I love sports fans. Without the painted-face people, I’d be writing ad copy for weedeaters. But I have I ever been a sports fan. A fan of reporting, yes. Of journalism. Of newspapers. A fan of reading and writing, you bet. I am a fan of sports, which is different from being a sports fan of the Simmons stripe.

The art and craft of competition fascinates me. Sports gives us, on a daily basis, ordinary people doing extraordinary things and extraordinary people doing unimagined things. I love it.But I have never cared who wins. I am a disciple of the Pulitzer Prize-winning sportswriter Dave Anderson, whose gospel is: “I root for the column.” We don’t care what happens as long as there’s a story.

My readings of Simmons now suggest he is past caring only about the Red Sox, Celtics, Bruins, and Patriots winning (though if they all won championships in the same year, the book would be an Everest of Will Durant proportions). He now engages, however timidly, in actual reporting of actual events; he even has allowed that interviewing people might give him insights otherwise unavailable on his flat-screen TV. Clearly, though, he is most comfortable in his persona as just a guy talking sports with other guys between commercials – which is fine if, unlike me, you go for that guys-being-guys/beer-and-wings nonsense and have infinite patience for The Sports Guy’s bloviation, blather, and balderdash.

Even though Bill James has written almost exclusively about baseball, for traditional newspaper and magazine guys, I doubt that he’d qualify as a sports writer. Not without reporting, or going into the locker rooms. Then where does that leave guys like Joe Sheehan, Tim Marchman, Jonah Keri and Rob Neyer (to name, just a few)? They aren’t fans like Simmons, but they write soley about sports.

The definition of what it is to be a sports writer is changing.

I have done some freelance writing for SI.com, gone into the locker rooms and filed stories. I’ve also worked on longer bonus pieces too. I enjoyed both experiences because it gave me an appreciation for the rigors of journalism. I also came to realize that being a beat writer, for instance, is not a job for me–I’m too old and I don’t have that kind of hustle and I don’t care enough about where being a good beat writer would take me.

Nobody grows up dreaming of beinga columnist anymore do they? I suspect they dream of growing up and writing, or blogging, so that they can be on TV.

Here at the Banter, I’m more like Simmons or Angell. I’m not a reporter or a columnist or an analyst, and I’m certainly no expert (I’m lucky to have a sharp mind like Cliff writing analytical pieces in this space). I think of myself as an observer. More than a strict seamhead, I write about what it is like to live in New York City and root for the Yankees. Often, I’m just as interested in writing about my subway ride home or the latest Jeff Bridges movie as I am about who the Yankees left fielder will be next year. Which makes the Banter more of a lifestyle blog than just a Yankee site, for better or worse.

So I’m no sports writer and that’s cool but I’m not sure what a sports writer is anymore.

…Oh, and along with Kindred, the inimitable Charlie Pierce has started a blog at Boston.com. Pierce is a welcome addition to the landscape. Be sure to check him out.

When I was a kid, I looked through my dad’s extensive library of books and through his record collection. Most of the books didn’t appeal to me because they didn’t have pictures. There was a history of burlesque that was titillating, a book about the history of the Academy Awards, and two of the Illustrated Beatles books; otherwise, his books didn’t interest me until much later. The record collection was mostly made-up of Original Cast Recordings from Broadway shows, and folk music joints, from Burl Ives to the Weavers. My mom had some Simon and Garfunkel and Judy Collins lps in the mix, and there was a copy of A Hard Day’s Night, but that was as rockin’ as it got.

What was left? A handful of comedy records–Why Is There Air? and I Started Out as a Child by Bill Cosby, Vaughn Meader’s First Family record, the 2000 Year Old Man, and the 2013 Year Old Man, by Mel Brooks and Carl Reiner. My twin sister, Sam, younger brother, Ben, and I listened to the Cosby and Brooks-Reiner records until they were practically worn-out. We can quote them without thinking. Every time I get off the phone with my sister we say, “Goodbye…I hope I’m an actor,” a throw-away line from Brooks in the Coffee House sketch on the first 2000 Year Old Man album.

Sometimes, before my parents got divorced, the old man would listen with us and we would wait with bated breath for the parts that made him laugh. I practically memorized what jokes got him going. He had a big, almost violent laugh that shook the room. It was exciting and scary but a relief: the old man was happy, and that was enough for us.

It’s hard for me not to think of my dad and Mel Brooks together–it is as if Mel is part of the family, just like George Carlin was. Although the old man wasn’t a great fan of Mel’s movies, he never tired of the 2000 year old man routine. Brooks has made a couple of memorable movies but his true genius is captured on these recordings, or on some of his talk show appearances. (Have you ever read the 1975 Playboy interview with Brooks? It is nothing short of hysterical.)

So I smiled this morning when I read the following interview with Brooks and Reiner in the Arts and Leisure section of the New York Times (they are promoting a new boxed-set of the 2000 recordings):

Q: How did you first come up with “The 2000 Year Old Man”?

MEL BROOKS: At the beginning it was pure made-up craziness and joy, and there was no thought of anybody else hearing it except maybe a couple of dear friends at a party.

CARL REINER: It was to pep up a room. We started on “Your Show of Shows,” and sometimes there would be a lull [in the writers’ room]. I always knew if I threw a question to Mel he could come up with something.

BROOKS: We had fun.

REINER: I remember the first question I asked him. It was because I had seen a program called “We the People Speak,” early television. [He puts on an announcer voice] “ ‘We the People Speak.’ Here’s a man who was in Stalin’s toilet, heard Stalin say, ‘I’m going to blow up the world.’ ” I came in, I said this is good for a sketch. No one else thought so, but I turned to Mel and I said, “Here’s a man who was actually seen at the crucifixion 2,000 years ago,” and his first words were “Oh, boy.” [He sighs.] We all fell over laughing. I said, “You knew Jesus?” “Yeah,” he said “Thin lad, wore sandals, long hair, walked around with 11 other guys. Always came into the store, never bought anything. Always asked for water.” Those were the first words, and then for the next hour or two I kept asking him questions, and he never stopped killing us.

BROOKS: It was all ad-libbed, and nothing was ever talked about before we did it. We didn’t write anything, we didn’t think about anything. Whatever was kinetic, whatever was chemical, we did it.

Here goes a sample…

From the first record:

For most of us, death will not announce itself with a blare of trumpets or a roar of cannons. It will come silently, on the soft paws of a cat. It will insinuate itself, rubbing against our ankle in the midst of an ordinary moment. An uneventful dinner. A drive home from work. A sofa pushed across a floor. A slight bend to retrieve a morning newspaper tossed into a bush. And then, a faint cry, an exhale of breath, a muffled slump.

My father died on this day two years ago. He was at home with his wife. They were getting ready to watch their favorite TV show. He had just eaten his favorite pasta dish. He slumped over in his chair and that was it. He officially lasted until the next day but really that was when he left us.

I always imagined that he would have a dramatic death. He was a big-hearted and volatile man. He was unafraid to get into it with, well, virtually anyone. I saw him kick the hub cap off a moving vehicle that had cut us off on West End Avenue and 79ths street, and was with him when he pulled a vandal out of a parked car. I thought he’d die in a pool of blood. I worried about it constantly. But he left quietly.

I think about him less now. Of course, I still think about him but I am not consumed with it as I was for the first year after he died, when his absence was acute. Almost every block in the city, certainly on the Upper West Side where he lived, holds a memory, some happy, others not so much, of the old man. I miss his stories, I miss asking him questions about the theater and the Dodgers and Damon Runyon.

But I don’t miss how tough he was on me, or the fact that even as an adult, I felt anxious around him. I don’t miss how competitive he was with me, and I don’t miss worrying about his financial state. When he was alive, I don’t think there was a time when I wasn’t afraid of him, even if it was on a subtle or subconscious level.

I feel relief now that he’s not around. I loved him very much and the feeling was mutual. He was proud of me, he was proud all of his kids, as well as his neices and nephews. He and I buried the hachet long before he died and I tried my best to accept and love him for who he was not what I wanted or needed him to be when I was a kid. Like most parents, he did the best that he could.

But I don’t compare myself to him these days. I am my own man. I remember his warmth and compassion, his laugh and his righteous indignation, and that for all his flaws he was a good man. I’m proud to be his son.

For most of us, death will not announce itself with a blare of trumpets or a roar of cannons. It will come silently, on the soft paws of a cat. It will insinuate itself, rubbing against our ankle in the midst of an ordinary moment. An uneventful dinner. A drive hom from work. A sofa pushed across a floor. A slight bend to retrieve a morning newspaper tossed into a bush. And then, a faint cry, an exhale of breath, a muffled slump." *

A Ridiculous Will —Pat Jordan

The summer is almost over: The last days of Yankee Stadium are upon us. Over the weekend, my neighborhood was crowded with kids returning to Manhattan College. A few days ago I went to Brooklyn to get my haircut. I hadn’t been in a few months and was starting to look downright shaggy. When I walked into the shop, early in the morning, the owner Ray was sitting in his chair. I noticed the place looked bigger and asked where my barber, Efrain was.

"He’s gone," said Ray.

As in retired, not dead. Up and left three weeks ago. Moved to Florida with his wife. Didn’t tell any of his few remaining clients. He only gave Ray a few days notice.

"His legs have been hurting him," said Ray.

I felt stunned although not surprised. I had been waiting for the day that I walked into the shop to discover that Efrain was gone–retired or dead–for some time now. I sat in Ray’s chair and listened to him as he cut my hair. But I didn’t really hear him. I could only think back on Efrain.

During and immediately after the War there was precious little work to be found in Belgium, so my mother’s father, a man’s man in the Ted Williams mold (although far more reserved), who had a considerable amount of wanderlust, moved his young family to the Congo, where my ma lived from the time she was three (1947) until she was a teenager. I learned about my father’s family, from Russia and Poland respectively, mostly through the oral tradition, endless stories, and even some writings. But I learned about my mother’s family chiefly through photographs and 8 mm home movies, a) because of the language barrier (they speak broken English, I speak broken French), and b) because they took an extraordinary amount of pictures. You can imagine how exotic it was to me as a kid to see photographs of my mom in Africa. "You grew up there and you wound up in the suburbs?" I used to kid her when I was a wise-ass teenager.

As it turns out, my mom and dad met in Addis Ababa, of all places. 1966. My father was there working as a production manager on a National Geographic Special on Africa. My mother was there with a group of friends, making a short documentary for graduate school about their trip from Northern Africa down to Ethipia.

Dig this. Which one you think is Ma Dooke?

And here’s the old man, in full Elliott Gould mode:

So, where did your folks meet?

In his first installment of our series about the box set of the 1977 World Series, Jay Jaffe mentioned how much his father admired Reggie Jackson:

Reggie made a big impression on my father, himself a second-generation Dodger fan who had no truck with the pinstripes. Via him, Reggie gained larger-than-life status in my eyes. When we played catch, occasionally Dad would toss me one that would sting my hand or glance off my glove. If I complained, he’d shout, “Don’t hit ’em so hard, Reggie!” In other words, don’t bellyache, and don’t expect your opponent to cut you any slack.

Longtime readers of Bronx Banter know that not only was Reggie my favorite player as a kid but he was one of the few Yankees my Dad also enjoyed too. Shortly before my father died earlier this year, I wrote a memoir piece about him and Reggie Jackson. I was thinking a lot about the old man two days ago on Father’s Day, and thought now would be a good time to share this story with you.

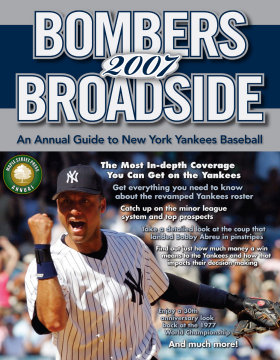

“Dad, Reggie, and Me” was originally published in Bombers Broadside 2007: An Annual Guide to New York Yankees Baseball (March, Maple Street Press). (c) 2007 Maple Street Press LLC. All Rights Reserved.

Dad, Reggie and Me

There is nothing like the first time. Nothing is as intense, as memorable as your first love, your first break-up or, in this case, your first hero. Mine was Reggie Jackson, who signed as a free agent with the Yankees 30 years ago. I was six years old during Jackson’s first year in pinstripes, a time when I was as interested in action heroes and comic books as I was in baseball. Reggie was more a superhero—a “superduperstar” as Time magazine once dubbed him—than a ball player. Bruce Jenner may have been on a box of Wheaties but Reggie had his own candy bar. (Catfish Hunter once said “I unwrapped it and it told me how good it was.”) Reggie arrived in New York at a time when I desperately needed a fantasy hero; his five volatile years in pinstripes coincided with the disintegration of my parents’ marriage.

The truth is the Yankees never wanted Jackson in the first place. In 1976, they won the pennant with an effective left-handed DH in Oscar Gamble. But after they were swept in the World Series by the Reds, Yankees owner George Steinbrenner was bent on adding a big name. The first free agent re-entry draft was held that fall and the Yankees drafted the negotiating rights for nine players. Reggie was their sixth choice. Steinbrenner and his general manager, Gabe Paul, coveted second baseman Bobby Grich; manager Billy Martin pined for outfielder Joe Rudi. Then, over the course of a few days in mid-November, seven of the nine players the Yankees were interested in signed elsewhere, and suddenly Steinbrenner had no choice but to court Reggie. Paul was against it, but Steinbrenner courted Reggie anyway, wining and dining the superstar around New York. In the end, Jackson couldn’t resist the Yankees anymore than Steinbrenner could keep himself from wooing the slugger. He turned down bigger offers from the Expos and the Padres and signed. “I didn’t come to New York to be a star,” he said. “I brought my star with me.”

I remember my father in those years sitting in his leather-bound chair, reading The New York Times, a glass of vodka constantly by his side. In 1976, we moved from Manhattan to Westchester and my father had a heart attack at the age of 39. He was unemployed for a year, horribly depressed. My mother got a job and chopped wood to keep our gratuitously spacious house warm. We moved to a nearby town, Yorktown Heights, in 1977 before my father began to work again.

As you can well imagine, yesterday was tough, and today feels even tougher. It feels so strange saying, “I watched my father die two days ago.” Here is the Death Notice from today’s Times:

Don Zvi Belth, 69, of the Upper West Side in Manhattan, died unexpectedly on Monday, January 15. Son of Helen and Nathan Caro Belth, loving husband of Kathy Neily, father of Alex, Samantha and Ben, father in law of Erin and Emily, grandfather of Lucas, brother of Bernice Belth, brother-in-law of Fred Garbers, nephew of Anita Fried, cousin of Don Fried, Paula Luzzi, Deborah and Mary Wallach, Rosanne Stein, and Stephen and Andrew Belth, uncle of Gordon Gray, Alexandra Pruner and Samantha Garbers. He will be remembered for his encompassing warmth, his humor, his intense loyalty and the vigor of his opinions. For the past 23 years Don has been an active and vital member of the Upper West Side recovery community. His passion for his beliefs and the way in which he shared them has been an ongoing gift to countless people and that voice is his legacy. His signature greeting, “Hello anyone,” is sadly now “Good-bye anyone.” The family will be receiving visitors at the home of Bernice Belth, 875 West End Avenue, on Wednesday and Thursday evening, from 6:00 to 9:00 PM. A memorial service will be held at a later date. Donations can be made in his name to the American Civil Liberties Union.

Pop wasn’t much of a sports fan as an adult, though he did admire the isolated great play if he happened to catch it on TV. He liked baseball best, and followed it casually in the Times. But growing up he was a passionate fan of the Brooklyn Dodgers–even though he was raised in Washington Heights, which was Giants or Yankee country. Dad liked to say that he was “second-to-none” as a fan of Jackie Robinson. He actually got Robinson to sign a copy of an early Jackie autobiography for him when he was a kid (Pop was ten-years old when Robinson broke the color barrier). Dad gave me the book when I was a teenager.

One thing was clear, though: Pop was a classic Yankee-hater. He hated them because the Bombers beat the Dodgers every year. Dad was 18 in ’55 when the Brooklyn finally defeated the Yanks in the Serious. That was a highlight for him for sure, but he seemed to have remembered the many defeats more than that one highlight. (He was riding in a car down the West Side highway with my grandparents when Bobby Thompson hit “the shot heard ’round the world.”) My grandfather was friends with a man who owned a company that printed the Yankees’ programs. This guy had box seats at The Stadium, just behind first base, and so my Dad went to see many of those World Series games in 47, 49, 52, 53, and 56.

Pop took me to see a handful of games as a kid–including an extra-inning affair in the early eighties where Bobby Murcer hit a game-winning dinger in extra innings against the Birds–and claimed to have never seen the Yankees lose in person. He stopped going to games, mostly because he wasn’t particularly interested in baseball, truth be told, but also because he felt he was a reverse jinx. If he went, the Yankees would win. And while Dad respected and even liked certain Yankees along the years–Reggie Jackson, Joe Torre, and Mariano Rivera come to mind–he absolutely loathed George Steinbrenner as a bully, and interloper.

One of Pop’s favorite Yankee moments when I was a kid involved Reggie. We were at a game where Jackson hit a game-winning bomb. I don’t have a clear memory of it, but according to Dad, it must have been in ’80, or ’81, maybe against the White Sox or the Brewers. Dad liked to tell me he called the shot, and I believe that he did. The following day, Pop was at Tiffany’s on Fifth avenue with his friend Jim Thurman. They spotted Jackson, wearing a fur coat, across the room looking at some jewelry. He was the toast of the town on that day. Thurman yelled out, “Hey Reg, good game last night. Who won?” Jackson, according to my dad, got a good laugh out of that, and my dad always laughed, deep and hard, whenever he told the story.

The language of baseball, the history and culture of baseball, is something that Dad and I used to communicate with each other, to remain connected. It was a safe topic when others seemed too uncomfortable or strained. It didn’t matter that he hated the Yanks. I could ask him about Cookie “Wookie” Lavagetto, and Pete Reiser over and again, as I would tell him about parts of the game I was writing about. He was proud of the book I wrote on Curt Flood, and we agreed that Marvin Miller was, and is, criminally underappreciated these days. It didn’t matter that we never shared great catches when I was a kid, baseball helped keep us together when we were adults. And for that, I am eternally grateful.